High school senior Martin Dimitrov signed up for the summer school on Bulgaria’s socialist past to make up for the lack of information on the topic in history textbooks and in the public discourse. Martin wanted to understand the almost universal nostalgia for the period among older generations. Bilyana Valkova heard about the program from her high school history teacher and enrolled because she wanted to know more about the country’s communist concentration camps. Sliven native Adelina Fendrina, a student at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, had studied the period as part of a special high school project and wanted to build on her knowledge.

High school senior Martin Dimitrov signed up for the summer school on Bulgaria’s socialist past to make up for the lack of information on the topic in history textbooks and in the public discourse. Martin wanted to understand the almost universal nostalgia for the period among older generations. Bilyana Valkova heard about the program from her high school history teacher and enrolled because she wanted to know more about the country’s communist concentration camps. Sliven native Adelina Fendrina, a student at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, had studied the period as part of a special high school project and wanted to build on her knowledge.

Martin, Bilyana, and Adelina were among 24 high school and college students from all over the country who spent a week in late June in the town of Belene, on the banks of the Danube, to learn more about the history of Bulgaria between 1944 and 1989. The past “came alive” for them when they visited the remains of the notorious Belene concentration camp on the Danube island of Persin and met with concentration camp survivor Khalil Rasim. In a small conference room overlooking the eerie island, Borislav Skochev—the author of the most comprehensive study of the camp’s 40-year history and a descendant of a former inmate—gave a vivid account of the inmates’ lives and the usually made-up accusations that had sent them there.

Apart from satisfying the students’ curiosity about this poorly studied period, the summer school on memory and remembrance, organized by the Sofia Platform Foundation with support from ABF, challenged participants to determine why and how contemporaries should remember this time and what lessons for the present history can teach them.

“We live in a political environment in which populists and demagogues increasingly raise doubts about the viability of democracy as a form of government. This is why it is so important for young people to know what the alternatives to democracy are and what price our parents and grandparents paid for the freedoms we take for granted today,” says Louisa Slavkova, executive director of Sofia Platform.

“We live in a political environment in which populists and demagogues increasingly raise doubts about the viability of democracy as a form of government. This is why it is so important for young people to know what the alternatives to democracy are and what price our parents and grandparents paid for the freedoms we take for granted today,” says Louisa Slavkova, executive director of Sofia Platform.

Some students cite personal reasons for attending the summer school, as they have relatives or acquaintances who were victims of communist repression. However, most participants are like Adelina, Martin, and Bilyana, who are looking to the past for answers to modern-day problems. Both Bilyana and Martin said the most interesting discussions were the ones comparing totalitarian regimes and democracy, precisely because these are relevant to them as citizens of a democracy today.

Adelina was surprised by the absence of hatred or desire for revenge in Khalil Rasim, who spent more than 20 years in different prisons on trumped-up charges without a trial. In his conversation with the students, Rasim highlighted the key role of free will and the inviolability of human rights in a democracy and called on students to respect the constitution.

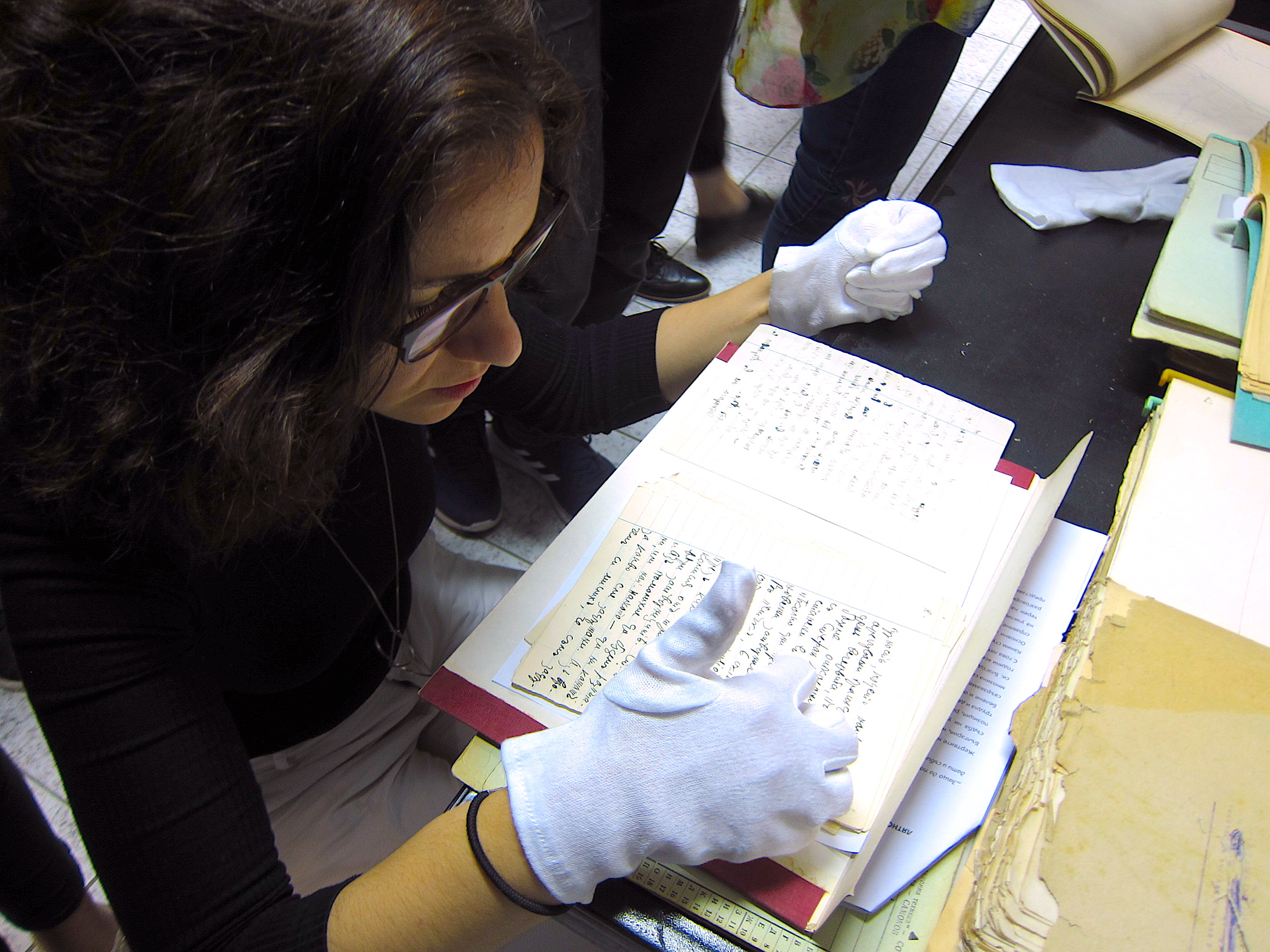

The summer school participants worked on their own projects on memory using archival documents and other sources. “The enthusiasm and detail with which they approached the task were inspiring,” says Mila Moshelova, project manager at Sofia Platform.

“Twenty-year-olds are more objective, more dispassionate about Bulgaria’s recent history. They are able to analyze events, accept and weigh arguments. All this makes the conversation more relaxed, more constructive,” says Daniela Koleva, an associate professor of culture studies at Sofia University. She challenged participants to debate whether remembrance is necessary at all costs and quoted examples from history in which a ban on remembrance was imposed to help heal social divisions. “The most widespread belief among the students was that we need to remember the past so we don’t repeat it. We need to remember as a duty to the victims, and also because memory is part of our identity,” Koleva says.

“Twenty-year-olds are more objective, more dispassionate about Bulgaria’s recent history. They are able to analyze events, accept and weigh arguments. All this makes the conversation more relaxed, more constructive,” says Daniela Koleva, an associate professor of culture studies at Sofia University. She challenged participants to debate whether remembrance is necessary at all costs and quoted examples from history in which a ban on remembrance was imposed to help heal social divisions. “The most widespread belief among the students was that we need to remember the past so we don’t repeat it. We need to remember as a duty to the victims, and also because memory is part of our identity,” Koleva says.

“Young people approach the subject more honestly and openly. I think the time has come to speak about communism and memory more calmly and rationally—to go beyond the politics and speak about values,” says Momchil Metodiev, a historian and researcher of modern Bulgarian history who lectured at the summer school. Should we remember? Metodiev answers by quoting Georgi Saraivanov, a political prisoner who was sentenced to death on fake charges at a very young age but managed to escape to Germany. “Forgetting the past is like driving a car without rear-view mirrors.”

“Without remembering the recent past, we won’t know how far we’ve come and whether we have succeeded, after so many years of protesting, in changing anything. Мy personal feeling is that, albeit slowly, things in Bulgaria are changing for the better,” Metodiev says.

Photos by Vanya Ivanova