We live at a time when we take camera-equipped phones and instant communication for granted, so it is hard for anyone in 2020 to imagine that week-old copy would count as “breaking news” and that, to convey the horrors of war, journalists would have to draw them, literally. Yet, it is through “breaking” days-old writeups and illustrations that people around the globe came to learn about the nineteenth century’s most covered war, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, which led to Bulgaria’s independence from the Ottoman Empire.

The event is marked every year on March 3, the date of the signing of the San Stefano peace treaty between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, and is known as Liberation Day in Bulgaria.

A new documentary, titled somewhat ironically Breaking News (the title is unchanged in Bulgarian), by Bulgarian film director Asen Vladimirov is dedicated to the nearly 100 foreign correspondents and illustrators who covered the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. Vladimirov used newspaper clippings from the time and other archival material to piece together what life at the front was like for these intrepid men and women. He looked at the work of journalists accompanying both the Russian and Turkish armies, examining their different perspectives on the geopolitical situation and their observations of Bulgarians.

The role of foreign correspondents, diplomats, writers, and public figures in drawing attention to the Ottomans’ merciless suppression of the April Uprising of 1876 in Bulgaria, which led Russia to declare war on the Ottomans and the western powers to abstain from obstructing it, has been well documented. Bulgaria has honored these men and women by erecting monuments and naming public spaces after them. (Prominent among these individuals are American journalist Januarius MacGahan, American scholar and diplomat Eugene Schuyler, British statesman William Gladstone, Russian general Mikhail Skobelev, Russian philanthropist and mother of General Skobelev Olga Skobeleva, who came to head the Bulgarian Red Cross, British illustrator and nurse Emily Strangford, English naturalist Charles Darwin, Irish playwright Oscar Wilde, Italian general Giuseppe Garibaldi, French writer Victor Hugo, Russian novelists Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Ivan Turgenev.)

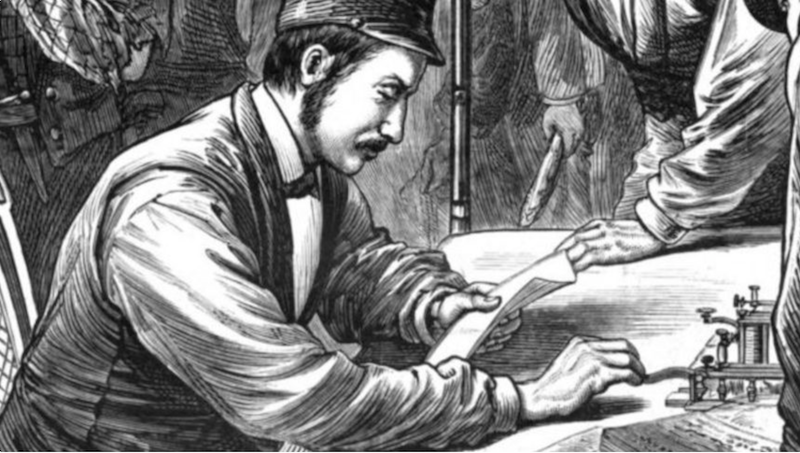

Breaking News, however, is the first detailed examination of the Russo-Turkish conflict through the work of nineteenth-century journalists. By doing so, it brings to the fore names that have not survived the test of time and memory and sheds interesting light on the state of the craft at the time. Journalism has always been an expensive business, but in 1877–78 the cost of doing journalism was exorbitant. Sometimes, to escape local censorship, foreign correspondents had to telegraph their copy from Austria-Hungary. Telegraphing a word of text from Vienna or Budapest cost 35 US cents, with some of the longer pieces costing up to $2,000, or about $35,000 in today’s currency. Journalists’ expenses included supporting an entourage of helpers, including a manservant, stableman, cook, etc. They also engaged the services of illustrators who were to create true-to-life images to go with the journalist’s copy. (Although by that stage the daguerreotype was in wide use, the technology was not suitable for capturing movement.)

And yes, getting a news report back to the newsroom took a week on average.

Despite the inherent difficulties in pursuing the craft and the high cost of doing so, Vladimirov’s research revealed that the Russo-Turkish War was the most widely covered conflict of the century, surpassing even the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Tellingly, it attracted the epoch’s biggest names in journalism.

Breaking News also features interesting anecdotes about the relationships and rivalries between the different correspondents. The film tries to present them objectively, without passing judgment on their biases. Journalists at the time openly took sides and changed their views on occasion; fabrications posing as news were not uncommon either, Vladimirov explained in an interview for Bulgarian news and analysis site kultura.bg.

Undoubtedly, coverage in the foreign press helped sway public opinion in Russia and western countries in favor of reining in Ottoman atrocities in Bulgaria and set off a series of events that led to Bulgaria’s independence.

Although it was celebrated before 1944, March 3 did not become the official state holiday in Bulgaria until 1991.