An unusual exhibition in a deserted village in the Eastern Rhodope Mountains traces the history of the so-called Revival Process of the 1980s and offers an unexpected lesson in patriotism.

An unusual exhibition in a deserted village in the Eastern Rhodope Mountains traces the history of the so-called Revival Process of the 1980s and offers an unexpected lesson in patriotism.

(See full gallery below)

“I know my mother’s name was Svetla.”

Svetla’s 16-year-old daughter says this. The statement is matter-of-fact, almost toneless. Yet, everything about it is strange. Why the need to preface such a simple statement with “I know,” like it reveals some well-guarded secret? And why past tense? Svetla is not a long-lost parent; she raised her daughter. She is still doing it. Past tense is for historical figures and strangers from the past, not your own mother.

Yet, past tense is strangely appropriate when we talk about the Bulgarian citizens of ethnic Turkish origin who were forced to adopt new names and identities as part of a mass assimilation campaign by the country’s communist regime in the mid-1980s. At the time, these newly minted Bulgarians were strangers to everyone, including themselves. Imagine having lived next door to Hassan all your life and then waking up one morning and finding your neighbor’s door sign reading “Assen.”

These strangers existed only briefly: after about five years, Svetla got her birth name back, Selin. Having been born in the 2000s, Selin’s daughter never met Svetla. It is surprising that the girl even knows about Svetla given the almost-ubiquitous reluctance in Bulgaria to talk about the so-called Revival Process, which began with the name change campaign in 1984–85 and culminated with the expulsion of 360,000 Bulgarian Turks in the summer of 1989, which authorities cynically dubbed “The Great Excursion.” In Bulgaria, these events have acquired near taboo status; they resemble a family’s dirty secret everyone has agreed not to talk about. Those like Selin who experienced it would rather not remember it, while history textbooks contain a single paragraph about the topic.

Yet, the Revival Process left a profound mark on the family of 22-year-old photographer and researcher from Haskovo Bayryam Bayryamali and on the families of many of his peers. His mother, father, and their families are among the hundreds of thousands of Bulgarian Turks who were told by the government they had 24 hours to vacate their homes in the summer of 1989. This was the last and most horrible stage of the communist regime’s campaign to prove that there were no Turks in Bulgaria, that the people bearing Turkish names were, in fact, Bulgarians who were forcibly Islamized when Bulgaria was part of the Ottoman empire. Therefore, the regime would be “reviving” these individuals’ true identity.

The first stage of the revival involved replacing the names of between 800,000 and a million ethnic Turks with Bulgarian names. Ayshe became Assia, Hassan—Assen, Bayryam—Boris. Those who refused to change their names were punished. Not even the dead were spared: in many Turkish cemeteries, tombstones bearing Turkish- or Arab-sounding names were removed or replaced with Bulgarian inscriptions.

In 1989, the communist regime’s campaign against Bulgarian Turks reached new depths: in June, hundreds of thousands of people were told to pack up and leave the country. An estimated 360,000 Bulgarian Turks fled to Turkey in the next four months.

Tens of thousands returned in the months and years after the post-1989 regime change in the country. Among them was Bayryam’s family. A few years ago, Bayryam began researching the Revival Process not only to learn more about his family history but also to find out a little more about himself today—a young man who loves his country and wants to live in it even though he doesn’t always get love in return. He interviewed family members, studied newspapers and other documents from that time, spoke with historians, and visited depopulated villages in the Eastern Rhodope. The results of his research were shown in “The Great Return,” a pop-up art installation featuring objects, sound, and photos connected to the stories of ordinary people swept up in the Revival Process. The setting for “The Great Return” was the abandoned village of Oreshari, amid the ruins of houses and overgrown orchards and against the backdrop of spectacular scenery.

Between June 18 and 20, 150 high school students from southeastern Bulgaria made the trip to Oreshari to see Bayryam’s installation and to talk about the events that inspired it. Scholars Momchil Metodiev, Hristo Panchugov, Vanya Ivanova, and Nadezhda Zhechkova helped put the installation in perspective and answered students’ questions about the events of 1984–85 and 1989. Sofia Platform’s Louisa Slavkova and Borislav Dimitrov curated the installation and moderated the discussions. Conversations centered on the personal histories of people involved in the Revival Process as well as on stories of return. (One of Bayryam’s aunts, who was part of the exodus in 1989, made a brief appearance.) The discussions were also aimed at starting a conversation about the present—about how we should live in a society of ethnic, religious, and social differences.

Students’ experience of “The Great Return” began with a guided tour of the installation during which Bayryam supplied historical details, provided explanation, and answered questions. Only a few years older than the visitors, he spoke the same way they did—simply, without drama, with that special mix of hesitation and conviction typical of youth.

What he spoke about was less familiar: the household objects set amid crumbling stone walls, the portraits of Bayryam’s relatives and images from “The Great Excursion,” and the overgrown pile of rocks where the village school used to be, now marked with a piece of paper labeled “School,” told stories of heartbreak and separation that students could not quite imagine. Toward the end of the installation, visitors listened to an unusual concert—a Bulgarian song and a Turkish song being played simultaneously. While the combination was jarring and unpleasant most of the time, there were moments when the songs achieved surprising harmony.

Understandably, not all students were ready for a conversation about ethnic relations. Some of them had never heard about the communist regime’s forced assimilation of minorities. Others came believing that the nation stands above the individual, especially if that individual is a member of a minority group. Ultimately, there was overwhelming empathy for the fates of ordinary people and their families, with many of the visitors saying they were “sad,” “shocked,” and “upset” by what the Revival Process had done to them. They were disgusted that this was done in the name of the nation.

In Oreshari, students also heard stories about good neighborly relations, friendship, and even love between Bulgarians and Turks.

On the last day, a middle-aged couple joined the installation tour. They were silent through the tour and discussions, but they approached us at the end of the last session and struck up a conversation. They were ethnic Bulgarians from a town in southern Bulgaria with a mixed population. The woman told us that her best childhood friend had been a Turkish girl named Jamile. Then Jamile became Desi. “I never saw her again after 1989,” the woman said, swallowing back tears.

It took her husband longer to speak, but in the end, he told us about a conversation he had overheard in 1989 where military officials cynically discussed whether to give the “vacationers” a brass band sendoff. His account was full of indignation but also sounded like an apology—for having been in the privileged position of overhearing this in the first place.

Each visitor likely took away something different from the Oreshari experience, but they all saw Bulgaria through Bayryam’s eyes and learned that there was more than one way to love your country.

Where landscapes dazzle and time stands still

Oreshari is just off Road 593, on the way between the towns of Haskovo and Krumovgrad, a few miles after you cross the iron bridge over the Arda River. Although there is a paved road to the village and Oreshari has four residents according to official data from 2018, the reality is different: no one has lived here for decades. The village’s permanent inhabitants are field mice, hare, kestrels, and tortoises. The only vestiges of human presence are the overgrown ruins and long-untended walnut, mulberry, and plum trees.

We don’t know exactly when the village was abandoned, but the uniform dilapidation of the buildings suggests the last Oresharians likely left in the summer of 1989.

The sadness emanating from the ghost houses is as palpable as the beauty of the surrounding countryside. The combination is magical, making the vicinity of Oreshari ideal for contemplation and long walks in nature. Just be careful: it is enough to see the sun set over Oreshari just once to fall in love with the place and want to stay forever.

A sense of magical presence permeates the entire region. It is no surprise, then, that the place is home to many holy sites and has inspired many a legend. Must-see sites in the area are the bizarre rock formations called the Stone Wedding (according to legend, they are fossilized wedding guests) and the Stone Mushrooms, the ancient Thracian sanctuary of Perperikon, and the Devil’s Bridge, the largest bridge in the Rhodope, part of the ancient road connecting the Thracian lowlands to the Aegean coast. (As its name suggests, the many legends connected with it involve a losing bet with the Devil.) Today, the bridge is part of the Sultan’s Trail, an international walking route from Vienna to Istanbul that passes through nine countries.

Visitors can also enjoy beautiful sunsets as well as great fishing and kayaking at nearby Student Kladenets (Cold Well) Dam. If you need some solitary time, you should definitely visit the village of Lisitsite, on the dam’s southern shore. There, it feels like time stopped centuries ago: there are no roads either in the village or leading to it. The only way to reach it is by boat or rope bridge.

You can learn more about Oreshari and Bayryam’s art installation from this story by Nova TV (in Bulgarian): https://www.vbox7.com/play:41c566f288. Read an interview (also in Bulgarian) with Bayryam for Radio Free Europe: https://www.svobodnaevropa.bg/a/30012319.html

The Sofia Platform Foundation is a Bulgarian NGO working in the field of democracy building and civic education. The work of Sofia Platform is supported by the America for Bulgaria Foundation.

AN UNUSUAL INSTALLATION: A PHOTO STORY

22-year-old Bayryam Bayryamali is a visual artist from Haskovo. He has a degree in documentary photography from the University of the Arts in London. He is interested in the history of communist repression in Bulgaria and its aftermath.

22-year-old Bayryam Bayryamali is a visual artist from Haskovo. He has a degree in documentary photography from the University of the Arts in London. He is interested in the history of communist repression in Bulgaria and its aftermath.

“The Great Return” installation is Bayryam’s artistic response to the events of “The Great Excursion” of 1989. The installation was created with the support of Sofia Platform.

“The Great Return” installation is Bayryam’s artistic response to the events of “The Great Excursion” of 1989. The installation was created with the support of Sofia Platform.

Between June 18 and 20, more than 150 students from five Bulgarian cities traveled to the village of Oreshari to see the installation and participate in a series of discussions about the so-called Revival Process. Oreshari was depopulated after the events of 1989.

Between June 18 and 20, more than 150 students from five Bulgarian cities traveled to the village of Oreshari to see the installation and participate in a series of discussions about the so-called Revival Process. Oreshari was depopulated after the events of 1989.

The laughter of local school children once echoed here.

The laughter of local school children once echoed here.

The kitenik (а type of traditional bedspread) and a Rhodope blanket, symbols of domestic comfort in Bulgaria, seem out of place amid the remains of a house. Kiteniks and Rhodope blankets are used for both warming and decorative purposes and in the past were must-have items in every home in Bulgaria, regardless of their occupants’ ethnicity.

The kitenik (а type of traditional bedspread) and a Rhodope blanket, symbols of domestic comfort in Bulgaria, seem out of place amid the remains of a house. Kiteniks and Rhodope blankets are used for both warming and decorative purposes and in the past were must-have items in every home in Bulgaria, regardless of their occupants’ ethnicity.

Each part of the installation, set atop the ruins of houses and public buildings, introduces visitors to a fragment of the history of the “Revival Process.”

Each part of the installation, set atop the ruins of houses and public buildings, introduces visitors to a fragment of the history of the “Revival Process.”

Traditional Muslim wear hung out to dry. Wearing such clothes and speaking Turkish were both outlawed after 1984–85.

Traditional Muslim wear hung out to dry. Wearing such clothes and speaking Turkish were both outlawed after 1984–85.

Shepherd dogs straying from their herds are the only domestic animals you can see in Oreshari from time to time.

Shepherd dogs straying from their herds are the only domestic animals you can see in Oreshari from time to time.

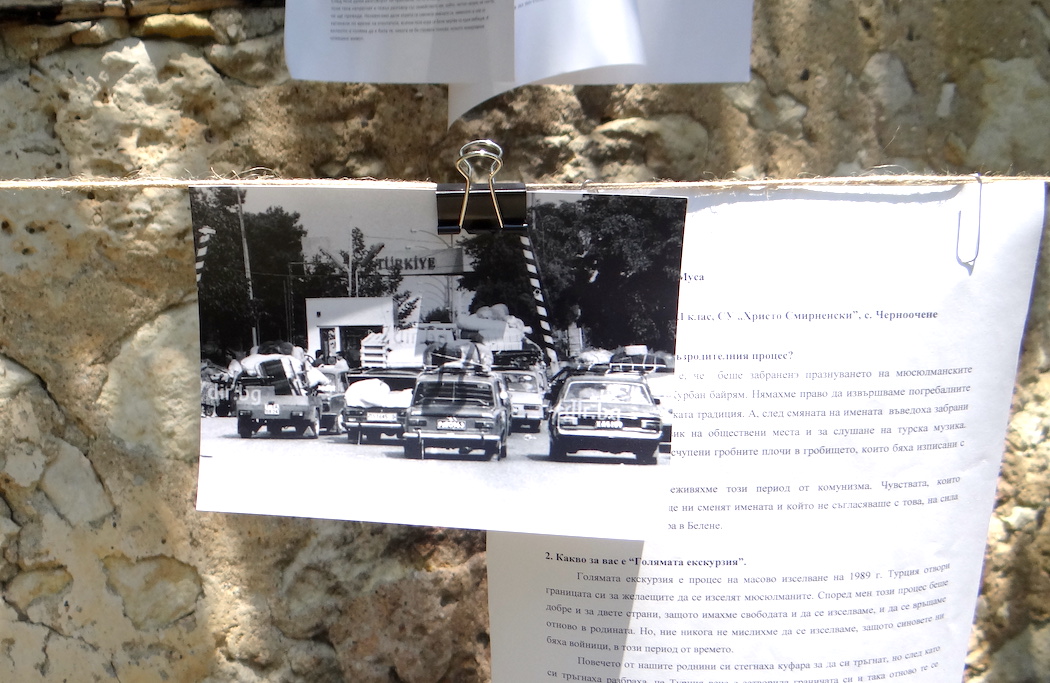

Photographs and written accounts of people expelled in “The Great Excursion” of 1989 on a clothesline

Photographs and written accounts of people expelled in “The Great Excursion” of 1989 on a clothesline

Students look at images and accounts of “The Great Excursion”

Students look at images and accounts of “The Great Excursion”

One of the best-known images from the summer of 1989: cars loaded with household goods at the Bulgarian-Turkish border. About 360,000 people fled to Turkey in the summer of 1989 before that country re-sealed its border with Bulgaria at the end of August.

One of the best-known images from the summer of 1989: cars loaded with household goods at the Bulgarian-Turkish border. About 360,000 people fled to Turkey in the summer of 1989 before that country re-sealed its border with Bulgaria at the end of August.

This site is dedicated to Bayryam’s family history.

This site is dedicated to Bayryam’s family history.

Bayryam’s family

Bayryam’s family

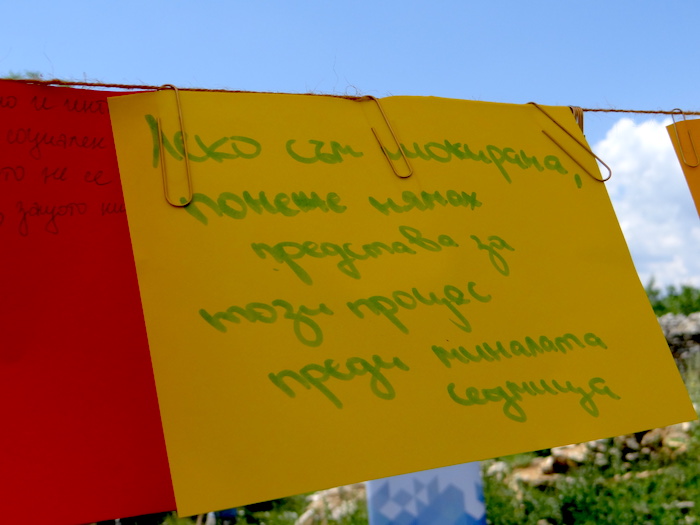

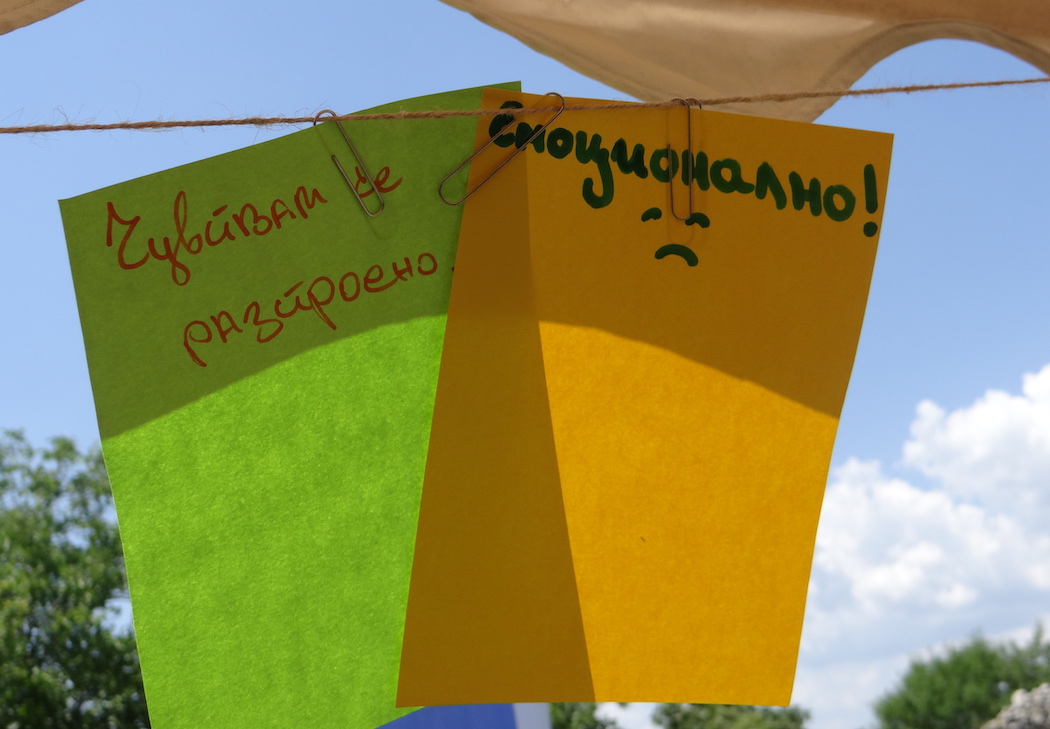

Colored pieces of paper bearing students’ reactions to Bayryam’s installation

Colored pieces of paper bearing students’ reactions to Bayryam’s installation

“I’m a bit shocked because I had no idea this had occurred until last week.”

“I’m a bit shocked because I had no idea this had occurred until last week.”

Nadezhda Zhechkova led discussions with students on the last day of the program. Zhechkova is an ethnologist and historian and the author of the study “Reintegration of Bulgarian Turks Returning from the So-called Great Excursion at the Beginning of Bulgaria’s Democratic Transition.”

Nadezhda Zhechkova led discussions with students on the last day of the program. Zhechkova is an ethnologist and historian and the author of the study “Reintegration of Bulgarian Turks Returning from the So-called Great Excursion at the Beginning of Bulgaria’s Democratic Transition.”

“I am upset.”

“I am upset.”

“This was emotional!”