“Belene is a three-colored flag woven from memory and oblivion… A place of memory no one wants to remember. A memorial to those who cannot forget it… I see it in white… The abandoned concrete high-rises of the Dimum neighborhood make my heart ache… Belene is green. Its natural beauty takes your breath away… Deep inside you know that Persin Island is mostly red. Like the communist regime that took advantage of it.”

“On this island time has stopped.

Is that a building poking through the weed?

Or is it someone’s dream? Perchance the souls of

wretched dreamers adrift in the July heat?”

From “Memories of Belene: 30 Years Later,” compiled by Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian, and Sofia Platform, expected publication September 2019

(Scroll down for a photo story about Belene)

When you are about to visit the site of a former concentration camp, you are prepared to be horrified. You are primed for desolate landscapes and grim reminders of human suffering. You expect to feel outraged and heartbroken. What you are not ready for is to be blown away by beauty and to find yourself in a place so fertile new life is everywhere—whether it is goslings waddling after their mother, young herons attempting first flight, poplar saplings reaching for the sky, well-fed livestock lounging in the shade of a tree, or vegetation pressing through cracks in the pavement.

In early summer, Belene Island (also known as Persin Island) resembles something out of a Gabriel García Márquez novel or a National Geographic documentary on natural habitats that refuse to be tamed by human presence: there’s lush vegetation that seems to grow back overnight even after extensive trimming and mowing, hundreds of bird colonies, swarms of dragonflies and other insects, grass that thrives in asphalt… The island, Bulgaria’s largest, belongs to the Belene Islands Complex—a Ramsar site since 2002, a protected wetland area of international importance that is home to hundreds of rare birds and plants. As such, the island is a paradise for birdwatchers and nature lovers. What is more, the tens of miles of paved track around Belene Island would make it an ideal destination for recreational cyclists and runners as well.

Yet Belene has a dark side, one that has overshadowed its natural beauty for decades. Throughout the communist era, the island hosted the infamous Belene concentration camp, where political prisoners were detained without trial and subjected to back-breaking labor and inhuman treatment, often for years, some of them never to return. To this day, there is a state penitentiary in the western part of the island, restricting access both to the nature reserve and to the site of the erstwhile concentration camp. Visitors need to apply for a permit from the Bulgarian Ministry of Justice in order to visit the island.

Over the years, many have questioned whether the continued presence of a prison on the site of the former camp is a good idea. Few, however, seem interested in changing the status quo; moreover, the subject is touchy among locals. The prison provides livelihoods to more than 150 families from the town of Belene, making it one of the largest employers in an area beset by a crumbling economy and high unemployment. Once envisioned as one of the main energy centers of the Bulgarian north, Belene Town today is dotted by gutted apartment buildings still waiting for the workers that were to staff the two failed energy plants. Those of Belene’s residents lucky enough to be employed mainly work in construction, manufacturing, and agriculture.

Belene’s contrasts are hard to reconcile, yet this is exactly what 23 high school and university students from across Bulgaria attempted to do over the course of a week in early July as part of a summer school on memory organized by Sofia Platform, an NGO working in the field of democracy building and civic education. Students’ exploration of Belene’s past, present, and future started an important conversation about how the country’s totalitarian past should be remembered and what lessons it should help Bulgarians draw for their present and future.

A Fading Memory

In Bulgaria, perhaps unfairly, Belene is a byword for communist repression. It was one of several “labor camps for reeducation,” and possibly not the worst one in terms of mortality, yet it was the one that existed the longest. It functioned almost uninterruptedly for four decades and held an estimated 15,000 people, 11,000 of them having never stood trial. Belene’s name struck fear in the hearts of those critical of or opposed to communist rule, and the Bulgarian communist party itself encouraged the fearsome reputation.

Today, that memory is fading. Thirty years after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, a reckoning with Bulgaria’s communist past is yet to take place, and study of the period has been relegated to the margins of the school curriculum. So, for information about pre-1989 Bulgaria, younger Bulgarians rely on their parents’ usually inaccurate and nostalgia-tinged accounts, at worst, or the initiative of history teachers or NGOs like Sofia Platform, at best.

Summer schools such as the one in Belene attempt to fill the gap in knowledge and enhance public debate about the communist era, and they do it through a mix of site visits, work with archival material, reflection, practical workshops, and seminars with researchers of the period. This year, the summer school’s second, lecturers included historians Daniela Koleva, Vanya Ivanova, Mikhail Gruev, and Momchil Metodiev, political scientist Hristo Panchugov, and Borislav Skochev, author of the most comprehensive history of the Belene concentration camp. Students also met with Belene community leaders such as Paolo Cortesi, a local priest, Mihail Marinov, director of the Belene Island Foundation, and Belene mayor Milen Dulev. Chief archivist Marinela Yordanova, of the state archives agency in Pleven, showed participants how to work with archival documents.

An Encounter with the Past

No amount of reading or discussion could fully prepare the students for their visit to the Belene camp site. There isn’t all that much to see, in fact, and a great deal is left to the imagination. Only a few crumbling buildings still stand, maintained largely thanks to the efforts of volunteers. A memorial to the victims of twentieth-century totalitarianisms on the site remains unfinished, and an exhibition of inmates’ portraits, sketched in pencil by a fellow inmate and smuggled out of the camp upon his release, gives their story a perversely fictional quality. Besides, it is hard to be outraged when surrounded by so much natural beauty on all sides. (That said, the July heat and swarms of mosquitoes recreated some of the discomfort that camp inmates must have felt, even as students reminded themselves that mosquito bites were likely the least of the inmates’ problems.)

Participants’ moving encounter with former camp inmates Khalil Rasim and Rusi Karapetkov was undoubtedly the program’s climax. Between the two of them, Rasim and Karapetkov spent a quarter of a century in Belene and other prisons. Rasim was 23 years old when he was imprisoned on trumped-up espionage charges. Karapetkov’s crime was setting up a high school club honoring a prominent figure in the Bulgarian agrarian party. He was only 18 when he was sent to Belene—the average age of participants in the summer school.

Despite students’ understandable requests for details of camp life, the two men refrained from graphic descriptions. They also showed no self-pity, although they’d spent a significant portion of their youth behind bars, for no reason and without due process. Instead, they concentrated on the present. Their message was clear and simple: Don’t forget. Don’t let that happen again. Defend democracy and democratic freedoms.

Whither Belene?

The encounter sparked a variety of feelings: indignation, outrage, sorrow, sympathy, resolve. It also raised many questions: What is the best way to honor victims’ memory? Why haven’t we done more as a society? What are the dangers of forgetting? Students also pondered the future of Bulgarian democracy in the face of worsening living standards for some, ubiquitous nostalgia for the perceived stability of the communist era, and shrinking belief in democratic values among some Bulgarians. “What can we do?” was a question at the back of everyone’s mind.

In one answer, the students were unanimous: we need to remember the past so as not to repeat it. One student wrote: “It is much easier not to remember. It is easier not to be burdened by knowledge of your past. But if you remember, you find sense, you find a reason to live. If you know how thousands lost their sweetest years, you realize that there is no time to lose. If you have the knowledge, the possibility that history will repeat itself disappears.”

The way forward was clear to most students in the summer school: Look to the future. Turn the concrete jungles into something positive. Preserve the memory of past atrocities but let Belene redeem its reputation as the country’s bogeyman. Students’ trips into town, encounters with locals, and a boat ride around the islands provided insights into how this can be done in practice. Belene should become a place of history and memory as well as a place of recreation. One student suggested that abandoned buildings in town could be creatively transformed by entrepreneurs and put to new uses that serve Belene’s population. The area’s natural beauty, cultural heritage, and human capital are rich resources ready to be tapped into.

A few enterprising locals are already using this potential. Hotel Prestige, perched on the riverbank overlooking Belene Island, is well managed and offers good price-quality balance. Plan ahead and organize your Belene camp visit by contacting the Belene Island Foundation at least two days in advance. Or you can go further back in time by visiting the ruins of first-century Roman military fort Dimum, next door to Hotel Prestige. You can also book a fishing trip or a boat ride to nearby islands with local fishermen through your hotel.

Visiting Father Cortesi is part of the Belene experience as well. An Italian by birth but a citizen of the world by persuasion, this down-to-earth, sharp-tongued polyglot Catholic priest is your best guide to Belene, town and island. Both his tireless work to preserve communism victims’ memory and his efforts to inject new life into the local community have earned him respect nationwide. He was the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee’s Human of the Year in 2017.

Last but not least, Belene is part of an increasingly popular bike route that connects Bulgaria’s northwesternmost city, Vidin, with the Black Sea. Within biking distance are the towns of Svishtov and Nikopol, where history buffs will find plenty of ancient and medieval ruins to linger around as well.

Students recounted their experiences at the Belene summer school from July 1–5, 2019, in a book of poems, essays, and photos, to be released by Sofia Platform in September 2019. Their work was curated by artists Krasimira Butseva and Julian Chehirian, who taught practical workshops on using art to talk about the communist legacy.

The Belene summer school on memory and democracy is organized by Sofia Platform with support from the America for Bulgaria Foundation.

BELENE: A GALLERY

Throughout human history, the earth’s great rivers have engendered life and nurtured vibrant civilizations along their banks. The Danube, Europe’s second-longest river, is no exception. Not only is the river home to striking natural habitats, but also some of the continent’s grandest cities straddle its banks.

Throughout human history, the earth’s great rivers have engendered life and nurtured vibrant civilizations along their banks. The Danube, Europe’s second-longest river, is no exception. Not only is the river home to striking natural habitats, but also some of the continent’s grandest cities straddle its banks.

The Danube’s Bulgarian banks, dotted by impoverished towns and villages, are a stark contrast to the prosperity along the rest of its 1,800-mile course, a recent article in Bulgarian weekly Capital points out. And nowhere is this more obvious than near the town of Belene, where crumbling and abandoned communist-era buildings coexist with breath-taking natural beauty.

The Danube’s Bulgarian banks, dotted by impoverished towns and villages, are a stark contrast to the prosperity along the rest of its 1,800-mile course, a recent article in Bulgarian weekly Capital points out. And nowhere is this more obvious than near the town of Belene, where crumbling and abandoned communist-era buildings coexist with breath-taking natural beauty.

An abandoned merry-go-round

An abandoned merry-go-round

One of Belene’s many concrete skeletons

One of Belene’s many concrete skeletons

Twenty-three high school and university students attended the summer school on memory and remembrance in Belene on July 1–5, 2019.

Twenty-three high school and university students attended the summer school on memory and remembrance in Belene on July 1–5, 2019.

Students working on a book of photos, poems, and essays

Students working on a book of photos, poems, and essays

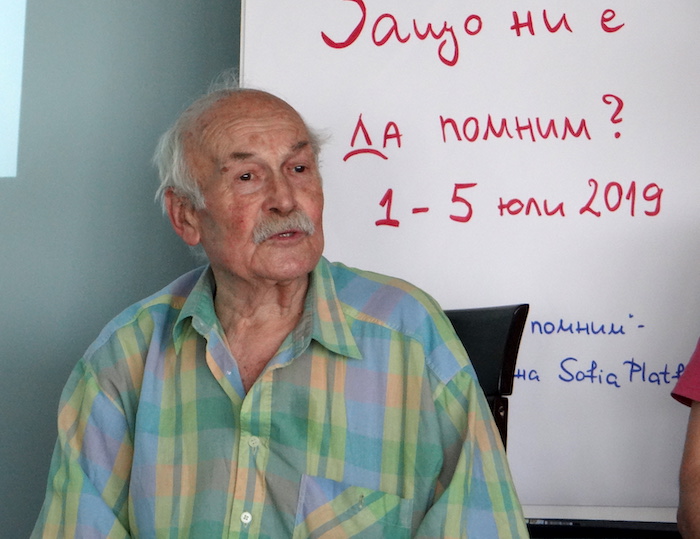

Sofia Platform director Louisa Slavkova and Belene survivor Khalil Rasim

Sofia Platform director Louisa Slavkova and Belene survivor Khalil Rasim

Rusi Karapetkov was imprisoned without trial in 1953, when he was 18 years old. He spent three years in the Belene concentration camp before being moved to the prison in Pleven.

Rusi Karapetkov was imprisoned without trial in 1953, when he was 18 years old. He spent three years in the Belene concentration camp before being moved to the prison in Pleven.

Khalil Rasim, Rusi Karapetkov, and 2019 Belene summer school participants

Khalil Rasim, Rusi Karapetkov, and 2019 Belene summer school participants

The pontoon bridge connecting the town of Belene and Belene Island. The sign reads: “Transporting people over the bridge is prohibited.”

The pontoon bridge connecting the town of Belene and Belene Island. The sign reads: “Transporting people over the bridge is prohibited.”

The entrance sign reads: “Yes, man sounds proud! Labor Reeducation Facility – Belene. Site 2.”

The entrance sign reads: “Yes, man sounds proud! Labor Reeducation Facility – Belene. Site 2.”

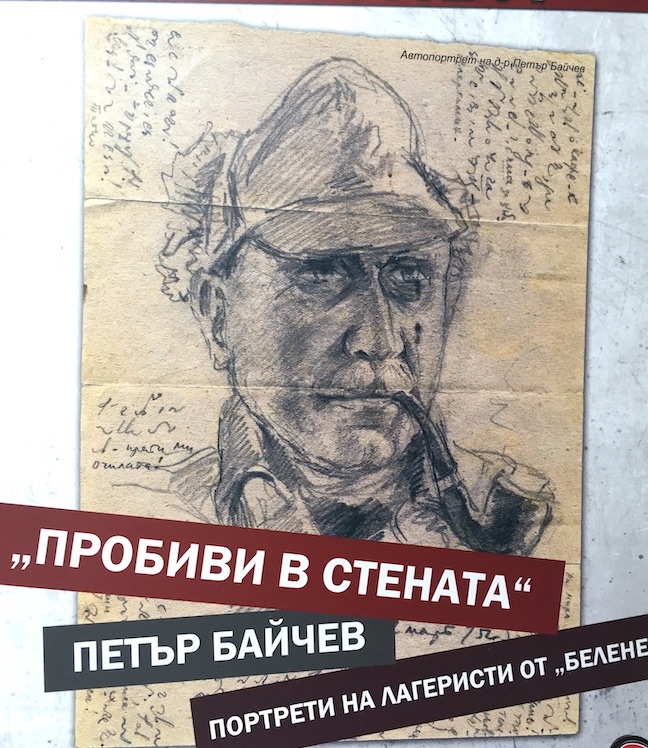

Interior of a Site II building and panels from the “Breaks in the Wall” exhibit

Interior of a Site II building and panels from the “Breaks in the Wall” exhibit

“Breaks in the Wall,” an exhibit of portraits of Belene camp inmates, hand-drawn in secret by Petar Baychev, a lawyer, artist, and former inmate. The exhibition can be seen at Site II of the Belene concentration camp.

“Breaks in the Wall,” an exhibit of portraits of Belene camp inmates, hand-drawn in secret by Petar Baychev, a lawyer, artist, and former inmate. The exhibition can be seen at Site II of the Belene concentration camp.

Student looking at the Belene exhibit

Student looking at the Belene exhibit

Designs for the planned memorial to the victims of the Belene concentration camp

Designs for the planned memorial to the victims of the Belene concentration camp

Students posing in front of the unfinished memorial to the victims of the Belene concentration camp. 2019 marks the seventieth anniversary of the camp’s opening.

Students posing in front of the unfinished memorial to the victims of the Belene concentration camp. 2019 marks the seventieth anniversary of the camp’s opening.

Belene is home to tens of square miles of marshland

Belene is home to tens of square miles of marshland

Grass poking through cracks in the pavement

Grass poking through cracks in the pavement

Cows whiling away the afternoon heat

Cows whiling away the afternoon heat

A great spot for birdwatching

A great spot for birdwatching

Back in Belene Town, students visit the remains of the first-century Roman military fort Dimum.

Back in Belene Town, students visit the remains of the first-century Roman military fort Dimum.

Father Paolo Cortesi, Belene parish priest

Father Paolo Cortesi, Belene parish priest

A boat trip is a great way to explore the islands making up the Belene Island Complex, of which Belene/Persin Island is the largest.

A boat trip is a great way to explore the islands making up the Belene Island Complex, of which Belene/Persin Island is the largest.

“I love the Danube.”

“I love the Danube.”

Sunset over Belene Island

Sunset over Belene Island

Photos by Petya Valkova, Krasimira Butseva, Louisa Slavkova, and Sylvia Zareva