Being an only child taught Rositsa Tropcheva to be resourceful. She made up her own entertainment. She learned to solve problems creatively. When she was seven, her dad taught her to ride his motorcycle. She was too short to get on and off, yet she didn’t want to wait for her size to catch up with her ambition. So, she came up with a workaround: she would mount and dismount on a nearby park bench.

Being an only child taught Rositsa Tropcheva to be resourceful. She made up her own entertainment. She learned to solve problems creatively. When she was seven, her dad taught her to ride his motorcycle. She was too short to get on and off, yet she didn’t want to wait for her size to catch up with her ambition. So, she came up with a workaround: she would mount and dismount on a nearby park bench.

Another early lesson was in resource management: ever since Rositsa was in elementary school, she would get pocket money for the entire week in advance. She spread it out so meticulously her parents soon trusted her with her entire monthly upkeep ahead of time.

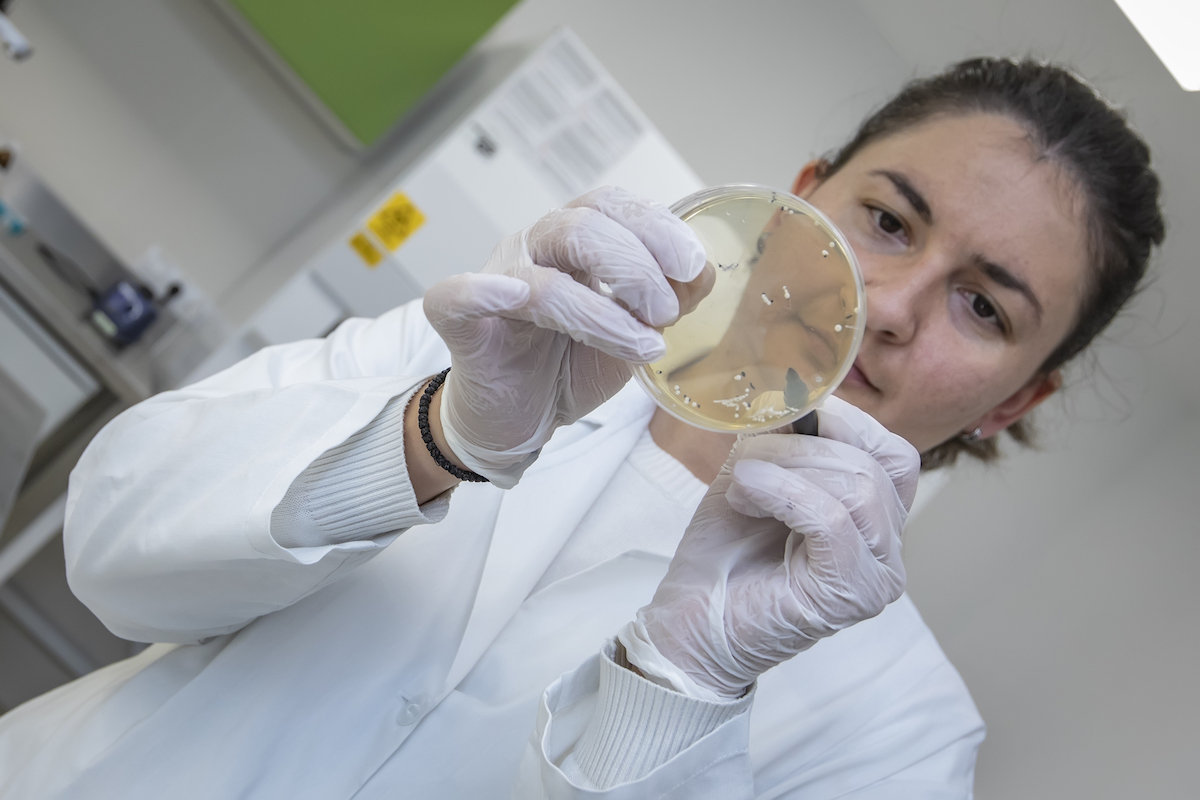

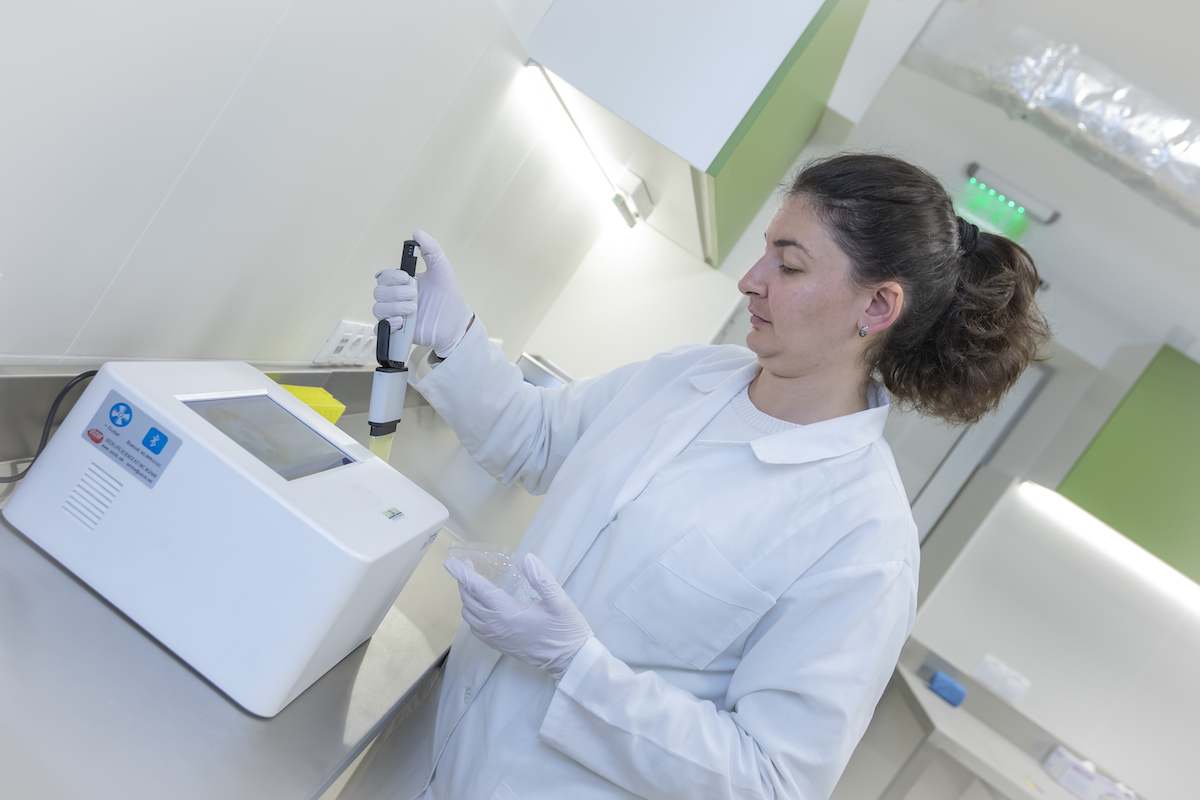

Determination, sensible resource administration, and problem-solving ability—these are what got her through a demanding master’s degree in industrial biotechnology and a doctorate in microbiology from the Stephan Angeloff Institute of Microbiology, part of the Institute Pasteur International Network and the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, and earned her the admiration of mentors and peers alike. Today, she puts all these qualities to use at the Center for Applied Studies and Innovation (CASI), Bulgaria’s first interdisciplinary laboratory for scientific innovation, which opened in the fall of 2018. The Center allows young scientists to test their ideas and look for viable science-based solutions to real-world problems while still at university. As CASI’s laboratory director, Rositsa is responsible for mentoring the students and supervising their experiments, stocking the labs, teaching classes, and developing marketable products to help pay for the Center’s operating expenses.

She is not alone in this task. CASI’s founder, Kiril Petkov, is an entrepreneur whose company, ProViotic, sells probiotics on four continents and who made a significant personal investment in the project. He teaches pro bono classes on the business side of developing biotechnology products. Support for the Center also came from the America for Bulgaria Foundation, and Sofia University gave it a home. Yet it was Rositsa’s creative thinking and experience from leading research centers that transformed a former university cafeteria kitchen into a truly interdisciplinary, world-class laboratory. She came up with a number of solutions to maximize the available space and make sample testing more cost-effective.

She is not alone in this task. CASI’s founder, Kiril Petkov, is an entrepreneur whose company, ProViotic, sells probiotics on four continents and who made a significant personal investment in the project. He teaches pro bono classes on the business side of developing biotechnology products. Support for the Center also came from the America for Bulgaria Foundation, and Sofia University gave it a home. Yet it was Rositsa’s creative thinking and experience from leading research centers that transformed a former university cafeteria kitchen into a truly interdisciplinary, world-class laboratory. She came up with a number of solutions to maximize the available space and make sample testing more cost-effective.

“I’ve put into this project literally everything I have learned so far,” Rositsa says. “I always keep my eyes and ears open and soak up everything—at every conference I attend, in every research fellowship and training opportunity. And I always try to figure out how to apply what I have learned.”

Her career path may not be long, but it is certainly impressive. After completing her doctorate in microbiology in 2014, she worked at the Angeloff Institute for a year. Contact with students was important to her, so Rositsa returned to her alma mater to teach in the biotechnology department, a position she continues to hold.

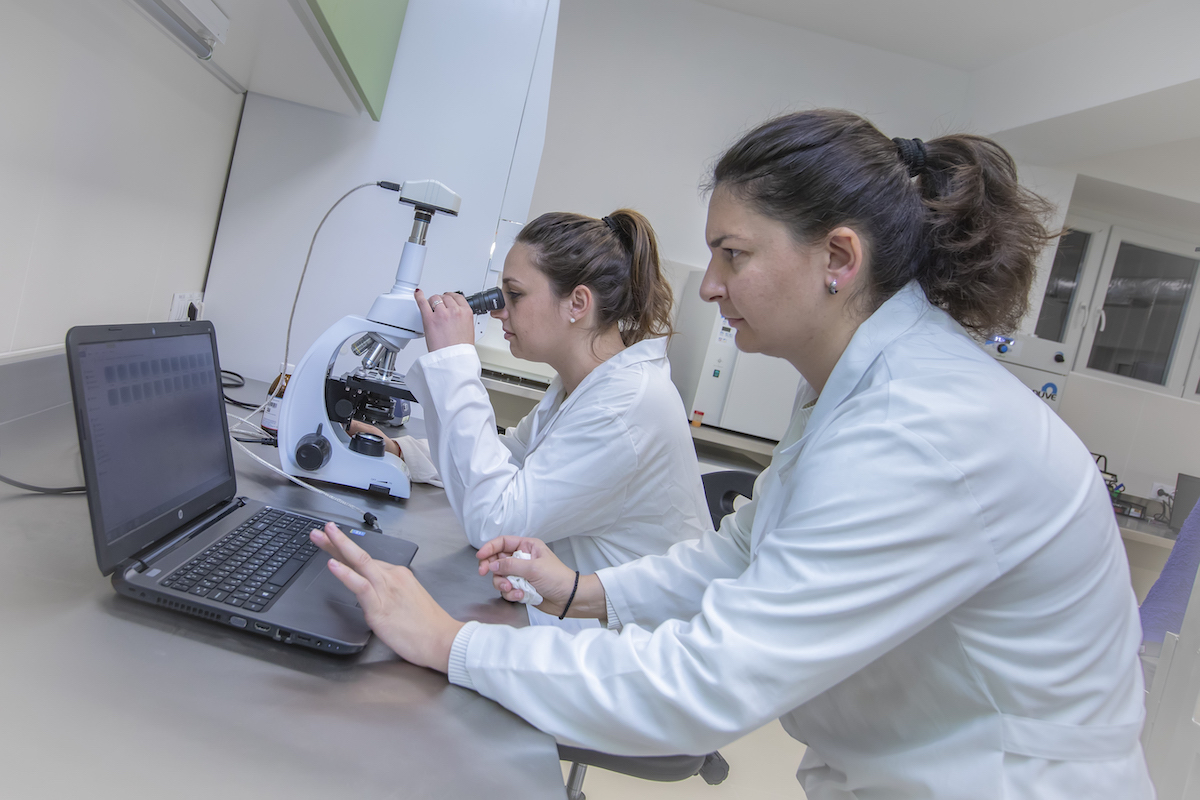

Rositsa’s dedication and love of teaching were recognized by students—and so was her approachable, down-to-earth personality—and a small group of motivated young scientists quickly formed around her.

Rositsa’s dedication and love of teaching were recognized by students—and so was her approachable, down-to-earth personality—and a small group of motivated young scientists quickly formed around her.

“She was always there for us students and taught us some very practical things to help us develop our technique and improve the work flow. She always explained things in detail, encouraged us to think for ourselves and to make connections between theory and practice,” says Emanuela Lukach, who was a fourth-year biotechnology student when she met Rositsa. Their meeting proved pivotal for Emanuela: Rositsa inspired her to pursue a master’s degree in biotechnology and take up research work in the field. Today, Emanuela is a biotechnology researcher at CASI and an assistant professor at Sofia University’s Biotechnology Department. “Everything I know and do as a biotechnologist and a teacher I owe to Rositsa.”

When she wasn’t teaching or helping students with their work, Rositsa took advantage of research and training opportunities worldwide. Her ability and thirst for knowledge took her to leading scientific institutions such as Harvard Medical School in the United States and the Pasteur Institute in Greece. In 2015, she spent two months at Hellenic Pasteur Institute in Athens at the personal request of Professor Haralabia Boleti, a renowned researcher in the biomedical sciences who had taught Rositsa and recognized her potential several years previously.

In 2016, Rositsa won a prestigious grant to study the protective effects of yogurt bacteria at the Laboratory of Genital Tract Biology at Harvard Medical School. The laboratory is also known as the Fichorova Lab after award-winning Bulgaria-born scientist Professor Raina Fichorova, who directs it and is globally renowned for her work in reproductive health.

Rositsa received lucrative job offers following both training experiences, but she rejected them in favor of returning to Bulgaria and running the CASI laboratory. Her reasons? “I believe in the project, and I like the idea of Bulgarians working in Bulgaria to develop things that are competitive on a global scale. What it takes is a good team, good ideas, and the willingness to work hard. Things are possible then.”

Her students are the other reason. “What keeps me here are all the smart, motivated young people I meet at the university. It may sound like a cliché, but they are worth staying here for. They always give me energy, and I learn from them too. It’s a two-way process: we teach them, but when there is positive feedback on their part, and we see their motivation and progress, it is really stimulating,” Rositsa says.

Her students are the other reason. “What keeps me here are all the smart, motivated young people I meet at the university. It may sound like a cliché, but they are worth staying here for. They always give me energy, and I learn from them too. It’s a two-way process: we teach them, but when there is positive feedback on their part, and we see their motivation and progress, it is really stimulating,” Rositsa says.

It is not all positive. “I have seen many promising science students change fields or leave Bulgaria in search of better conditions simply because they had nowhere to practice what they learned and no opportunities for advancement,” Rositsa says. “Of course, now that we have CASI, students don’t have that excuse.”

Several motivated students are already testing product ideas at the Center. One pilot study aims to develop a probiotic promoting cardiac health. Another project will examine whether bacteria in yogurt can fight off disease-causing microorganisms. A third student group is working on bio packaging for food, and a fourth wants to develop a bio lubricant.

These ideas may not work out, but others will. Rositsa’s aim is to impart the importance of thinking out of the box and not balking at challenges. “Good ideas come when you are up against the wall: when everything has been tried, and there’s no conventional solution. Only then do unconventional, innovative solutions appear. If everything is fine, if there are no problems, there will be no innovation.”