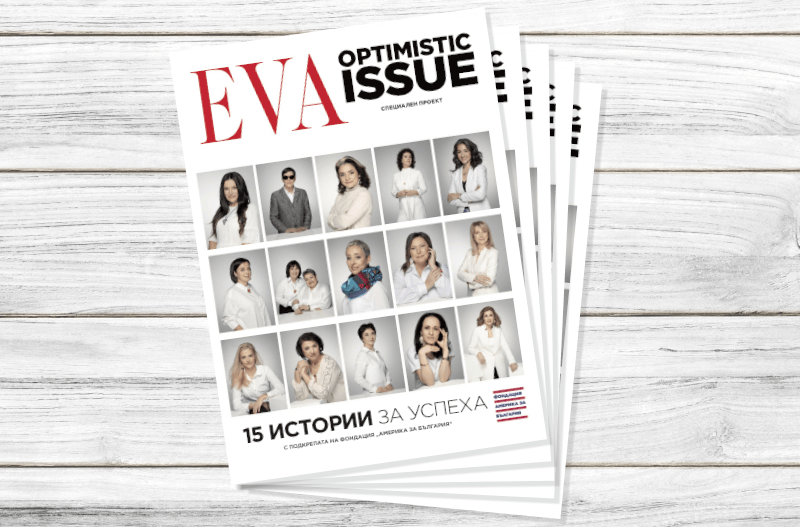

We partnered with Bulgarian lifestyle magazine EVA to present female leaders from the Bulgarian nonprofit and public sectors. The result was EVA’s Optimistic Issue: 15 Stories of Success. This is one of the featured stories, republished with permission.

Text: Kalina Konstantinova

Photos: Kostadin Krastev-Koko and personal archive

Translation from Bulgarian: Ana Blagova

Maria Methodieva is a philologist. She graduated in Bulgarian, French, and journalism from Saints Cyril and Methodius University in the city of Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria. For the first 15 years of her career, she taught French while running a business. Then she spent 10 years as a freelance consultant in the field of social work. She is the chairwoman of the St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Foundation, and, for the past five years, she has managed the Wonder Garden, a social enterprise in the northeastern Bulgarian town of Dobrich.

“Nothing is impossible. Even in Bulgaria.”

Since its creation in 1997, St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Foundation has worked to ensure a dignified and independent life for people with intellectual disabilities and their families. The foundation has initiated more than 30 projects, funding advocacy work and training social workers and parents of children with disabilities. The foundation has been a member of the Bulgarian Association for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities (BAPID) since 2004. It also developed the first pilot model for substitute care in Bulgaria, presenting the results before the Agency for Social Assistance, the national executive body in the field of social care. St. Nicholas the Wonderworker was the first organization to successfully end guardianships for people with intellectual disabilities, setting a legal precedent not only in Bulgaria, but in the whole of Eastern Europe as well. It is because of these achievements that, in 2016, Milena Stoyanova, the first woman to have her guardianship removed, and Maria Methodieva, were guests of honor on the occasion of December 3, the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, at the UN headquarters in Geneva.

The Wonder Garden is one of several projects run by the foundation. It’s a place where people with disabilities grow fruits and vegetables. No other social enterprise in Bulgaria employs so many people with disabilities. This makes the garden unique. Most of its employees are strangers to their families — they were abandoned to institutional care.

Ms. Methodieva, what motivated you to start the St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Foundation?

I had a very personal reason. I was a parent of a severely disabled child.

What were the major problems facing people with disabilities and their families when you started the foundation?

We were facing all kinds of problems. At that time, there were no additional allowances for children with disabilities, no social services, no trained experts… There was no internet, and no information. We would translate foreign books by hand in notebooks, copying them on carbon paper to share among the community… We would arrange for assistive aids to be bought via acquaintances abroad, and we would import them through an incredibly burdensome process because at the time only the Social Assistance Agency and municipalities could import them. The NGO’s only sources of funding were the EU’s pre-accession Phare program and foreign donors, where we had to submit projects in German, French, or English. We started the foundation in order to be able to lobby for social services. The first daycare center for children with disabilities was a small, unofficial group in a kindergarten, which started in 1999 with municipal funding.

Your foundation has been in existence for 26 years. Looking back, what are your greatest successes, and what goals have you set for the future?

Recently, when we received some donations from Bulgarians abroad, I made the sad joke that we started by handing out food parcels, and now, 26 years later, we have to do the same! Our greatest success? It’s probably that we didn’t give up, that we achieved a level of sustainability. We managed to remove the guardianships of several people and to develop pilot projects for substitute care and assisted decision-making. We created the first social enterprise to employ people with intellectual disabilities. Throughout this process, we’ve always had one goal: a life of dignity for people with intellectual disabilities and their families.

You have helped many people over the years. Are there personal stories that have remained with you, stories that particularly stand out?

You have helped many people over the years. Are there personal stories that have remained with you, stories that particularly stand out?

There are so many. I love all of them! You usually remember the latest best. The stories of people whose lives have been turned around for the better. I don’t know if people can fully imagine what it feels like to help someone’s life make a complete U-turn — someone who was not only destined to be born in an institution, but to spend their life there, deprived of all of their civil rights. Not only were we able to give a few girls their rights back, but we also managed to teach them how to defend and exercise those rights — and find fulfillment in the process. I think what makes me happiest is that our stories inspire many people and make them believe that nothing is impossible. Even in Bulgaria.

You managed to remove the guardianships of several people, setting a legal precedent in Bulgaria and Eastern Europe. Have there been other changes of similar importance regarding the rights of people with disabilities in Bulgaria since? Are there interesting practices from abroad that you would like to see applied here?

When in an emotional conversation with colleagues I said that I would challenge the guardianships of several people, I am not sure my mind fully comprehended what this would entail. Once it did, I realized how impossible it seemed, and I questioned whether I had the right to “play” with the lives of other people. Nevertheless, I put all my heart and energy into this cause. When we saw the first court ruling, my lawyer, Ms. Dalakmanska, and I couldn’t believe our eyes. We were overjoyed! Unfortunately, as with many of my professional successes, these remained an isolated miracle, not bringing about any larger reform. For the past twelve years, many of us — colleagues and like-minded individuals — have been fighting to strike down the Law on Guardianship of 1949. This law is not only morally outdated and discriminatory; it’s because of this law that the European Court of Human Rights has handed down two judgments against Bulgaria.

Recently, despite many obstacles, three new important laws in the field of social services entered into force. They are, to a large extent, modern in their philosophy and attitudes to the rights of people with disabilities. Unfortunately, we are yet to see a government that prioritizes social policy. We are light years away from the best practices in Europe: smaller municipalities offer no social services; social workers do not receive decent pay; there is a lack of key care professionals, and there is no support for training them; the administrative burden is too high; there are no mobile services; there’s no support for social enterprises… We still have to catch up on all of these aspects, but what makes us decisively different from Europeans farther west is the lack of tolerance and empathy for those who are different.

How would you describe your project the Wonder Garden? It has come a long way. What is in its future?

This had been a big dream of mine for a while. I am happy that I dared make it a reality and on an unheard-of scale at that. This was only possible thanks to the help of Dr. Ephraimov, who runs the foundation and the social enterprise together with me. The garden takes up all of our time and energy, because turning a thicket of shrubland into a garden — a Wonder Garden! — is very, very hard. We started with one acre of land next to the social services building, a lot locally known as “the Red Soil,” which was extremely hard to work. In other words, of all the fertile lands that the region of Dobrudzha is known for, we chose the least friendly lot. On top of it all, there was a gully four meters deep right in the middle of it, overflowing with brambles, trees, and thorny weeds. We chose this lot because it would be accessible to people with disabilities, who spend their time in the social services building nearby. They would otherwise find it challenging to navigate the city.

Two years ago, the municipality gave us an adjacent lot of 3.5 acres of land to use for free. The land was wooded, and, as a “bonus,” there were also three tiny swamps that we’re still working to drain. Despite all these difficulties, we have a lot to show for our five years of operation: 880 square meters of greenhouses, seven containers (an office space, a space for rest, a changing room, a tool shed, etc.), a truck, two tractors with a lot of equipment, a sawing robot, a groundwater well, and solar panels. We cover our own costs — through product sales, through project funding, and thanks to private and corporate donors. We have never asked for money. People who want to help us find their way to us.

We hope to be healthy and well, so that we manage to work all the land in the new garden. We want to decrease manual labor, to be able to pay everyone who works in the garden, and to be sustainable.

Do you agree with the quote, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing”? Do you see yourself as an active, good person?

You cannot be a good person if you do nothing. You can’t be happy while your neighbor is suffering, and we will never live happily as a society unless we fix our common home and everyone chips in as much as they can. That is, if we want to have a sense that we are doing good deeds. And I believe we all want this experience. It’s a matter of tuning in to oneself and hearing one’s inner voice. Even if it’s a quiet one. In my case, that voice is usually loud, and when it yells, I just can’t stand still. I recently started taking heart medication; I didn’t even know I had an unusually rapid pulse.

How did your partnership with the America for Bulgaria Foundation begin? Do you work well together?

How did your partnership with the America for Bulgaria Foundation begin? Do you work well together?

When I started the garden, I immediately began looking for project funding. In Bulgaria, project funding comes mainly from the nongovernmental sector. In our case, the America for Bulgaria Foundation funded our project twice, and last year they directed a Christmas donation to us. In all these instances, their help came right when we needed it the most. When they gave us the second grant, which was to clean up the new 3.5 acres, we, as usual, tried to spend every penny responsibly. We had a little money left at the end, and we were wondering how best to invest it, when our seemingly new tractor broke down. The spare parts would take a month to arrive, and we needed a tractor to harvest our cabbage (13 tons of it). The irony was that, in a pinch, we spent our last American money on an old Russian tractor.

Next year, we will be very happy to invite H.E. Ambassador Kenneth Merten and all our friends from the America for Bulgaria Foundation in person so we can demonstrate what happens in practice when American optimism meets Bulgarian potential.

Where do you find the inspiration and optimism to keep going?

This is my calling. I’ve known that I’m on the right track for many years now, and nothing can stop me from following it. The thing about optimism is that you either have it, or you don’t. If I didn’t believe strongly in everything we do at the foundation, we wouldn’t achieve anything. Faith brings about wonders, not the other way around. And when you’ve witnessed so many wonders, you will always find inspiration and try to cause the next one to happen with your faith.