In an authoritarian state, citizens aren’t encouraged to participate in public life in any real way except to show up at state-organized events and regurgitate the official line.

This is what makes democracy different. Democracies guarantee citizens’ right to express their opinion freely and act on their conscience. What is more, the success of a democracy hinges on citizens’ doing so actively and responsibly.

This idea is at the core of a new subject high school juniors and seniors in Bulgaria have to take starting this academic year.

In Civic Education classes, students will learn the differences between representative democracy and direct democracy and between majoritarian and proportional electoral systems. They will also grasp the importance of active civil society organizations and independent media for the health of a democracy.

However, knowledge of the advantages and building blocks of democracy isn’t the only purpose of the new subject. More importantly, it aims to raise awareness of what it means to be a citizen in a democratic state today and how individuals can be active participants in their local and national communities.

Students will also learn that civic engagement may take countless different forms. Writing an op-ed in the school newspaper to protest the lack of healthy food options in the school cafeteria; working with the city council to purchase more recycling containers for your neighborhood; blocking the construction of an apartment building in a schoolyard; and becoming an elections observer in order to ensure a ballot’s fairness are just some of them.

But do these need to be taught, and why introduce the subject now?

Threats to fundamental democratic values such as peace, equality, and human rights have made civic education a priority across European Union member states over the past decade, with EU countries investing in curricular improvements and extracurricular programs in the area. Epidemics, cyberthreats, the viral spread of conspiracy theories, and growing distrust in institutions and the media in much of the western world have driven home the need for citizenship education.

The year 2020, in particular, is so eventful and complex politically, socially, and economically that “there is hardly a better year for introducing the subject. The pandemic and the protests, seen through every new class topic, allow students to discuss different aspects of citizenship,” said Louisa Slavkova, one of the coauthors of the Civic Education textbook for Grade 11 and the director of Sofia Platform, an organization working in the fields of civic education, history of the recent past, and memory.

But Civic Education isn’t a fail-safe solution to democratic backsliding, nor is it meant to be simply a compass in the current political environment. “Most of all, it should help us acquire competences as citizens. Civic competences allow us to be active citizens—that is, the subject of civic education is not just about knowing and understanding, but about being empowered to do something with that knowledge. Mere knowledge does not make a citizen. There is no citizenship or democracy without practice,” Ms. Slavkova said in an interview for Bulgarian National Radio.

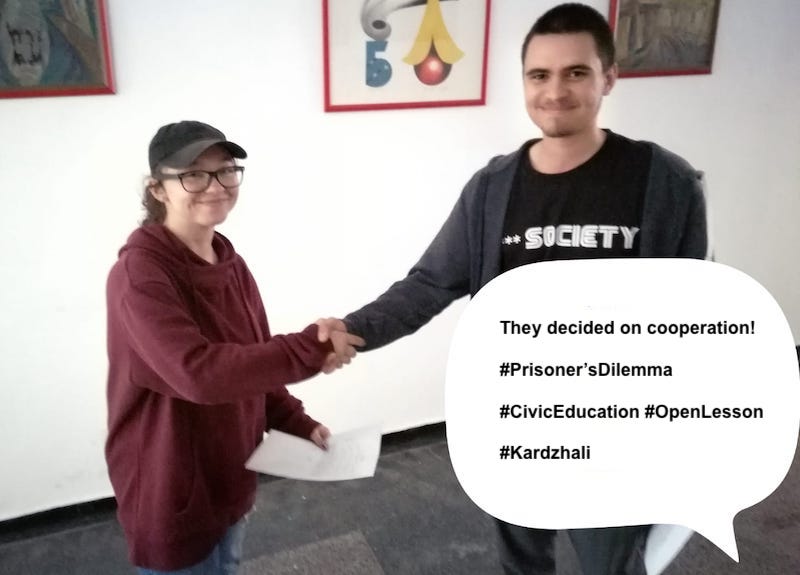

Through the America for Bulgaria Foundation’s long-term support, Sofia Platform has been instrumental in developing methods for teaching and learning civics and testing them in classrooms around the country. In 2018 and 2019, the organization’s trainers worked with 350 teachers to help them build competences for teaching the new subject. Sofia Platform also hosted or partook in public discussions on democratic citizenship and memory drawing hundreds of participants and conducted 56 open lessons with close to 400 students in 15 towns and cities across Bulgaria.

During interactive sessions, students discussed issues such as power and justice, civic engagement, minority rights, the role and function of an electoral system, and citizen control. And these weren’t just theoretical discussions: students organized a school referendum, prepared and submitted a petition to the local council, and simulated a municipal election. They were encouraged to apply creative problem-solving and lessons from entrepreneurship to address social ills.

In partnership with educational platform Ucha.se and the European Commission Representation in Bulgaria, Sofia Platform also developed a collection of educational videos on civics topics, which are available free of charge. The organization will continue to support teachers in 2020/2021 through further trainings and the development of teaching aids.

The civics curriculum envisions the use of movie screenings and discussions of real-life examples of student activism. One notable case is Swedish high school student Greta Thunberg’s environmental campaigning, which is lionized by some and criticized by others. “This is normal in a democracy,” said Professor Hristo Todorov, a coauthor of the Civic Education textbook. “It is normal to have different assessments. What’s important is that we have a good example of a civically active young person who is still in school.”

In the civics classroom, students will be encouraged to examine the opposing viewpoints.

The Grade 12 curriculum builds on knowledge and competences acquired in Grade 11 and introduces subjects such as globalization and threats to global peace such as terrorism, unequal access to resources, and climate change.

Equipped with the right tools, today’s students will become part of the solution to these problems tomorrow.