Adapted from Thanksgiving: The Holiday at the Heart of the American Experience (Encounter Books, 2016) by Melanie Kirkpatrick

Let us freely give

to the children of penury

and want among us.

—The Washington Daily Intelligencer, 1864

Sarah Josepha Hale, an influential 19th-century American magazine editor who championed the national celebration of Thanksgiving, identified one of the enduring features of the holiday as “generous beneficence to the poor.” This observation remains as true today as it was in 1870, when the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book wrote it. At no time of the year is American generosity more evident than at Thanksgiving, when large numbers of Americans donate to charitable causes and volunteer their services to help the less fortunate.

In his travels around the United States in the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville famously observed that Americans were constantly forming voluntary associations for the purpose of mutual aid and support. The inspiration for many such organizations was concern for the poor, with special attention given to their plight on Thanksgiving Day. Some of these charitable organizations still operate. The Bowery Mission has been feeding and sheltering homeless New Yorkers since 1879. The Salvation Army USA has been helping the poor in America since its founding in Philadelphia in the 1880s. Goodwill got its start in Boston in 1902 and then spread nationwide.

The relationship between Thanksgiving and generosity was reinforced thousands of times in the popular press of the day—in news articles about how the poor marked the holiday and how kind individuals, religious institutions, and charitable organizations came to their aid; in commentaries praising do-gooders and exhorting readers to do their part; and in the publication of sermons by local clergy urging readers to lend assistance to their fellow citizens.

The fiction of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is replete with uplifting moral tales of charity toward the less fortunate on Thanksgiving Day. A short story published in Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1863 is typical of the genre. In this particular story, a neighbor delivers a Thanksgiving dinner to a mistreated child by the name of Roxy, who exclaims: “I never expected to eat a mouthful to-day; and here’s a real Thanksgiving dinner for me! Chicken pie! cold ham! biscuit! cake! and I don’t know what else!”

***

Americans are the world’s most generous people, according to The Almanac of American Philanthropy (2016). When it comes to charitable giving, they are twice as generous as the Canadians or the British and ten or twenty times as generous as the people of other developed countries such as France, Germany, and Japan. Annual charitable giving accounts for 2.1 percent of the American gross national product, compared with 1.2 percent in Canada, 0.8 percent in the United Kingdom, and a paltry 0.1 percent in Germany. No other country comes close to the United States in its philanthropic donations.

In 2014, Americans donated $358.38 billion to charity. Of that sum, an astonishing 73 percent, or $258.51 billion, came from individual donors. Personal gifts from individual Americans account for four times as much, every year, as what foundations and corporations give away.

Americans have a long tradition of individual giving. Consider the following example from the Civil War. On Thanksgiving Day 1864, the second of the national Thanksgivings proclaimed by Lincoln, hundreds of small donations made it possible for five hundred wounded and sick soldiers at Armory Square Hospital in Washington, D.C. to enjoy Thanksgiving dinners.

As this story of Civil War philanthropy indicates, charitable giving in America is not limited to the wealthy. Throughout American history, people from all walks of life and wide degrees of means have given generously to charity. A significant portion of Americans’ annual charitable giving—as high as one-half, according to one survey of nonprofits—is done during the “giving season,” the period stretching from Thanksgiving to Christmas.

The tradition of Thanksgiving generosity also takes the form of volunteer work. The ladies who hosted the holiday dinner for wounded soldiers at Washington’s Armory Square Hospital in 1864 were not paid workers. They offered their services as cooks, servers, and companions. They decorated the dining hall, set the tables, cooked the meal, served the food, and assisted amputees who needed help walking to the dining hall or cutting their meat.

For many Americans today, helping a fellow American celebrate Thanksgiving is personal, sometimes intensely so. Volunteers sort food at local food banks, prepare and serve meals at soup kitchens, and deliver Thanksgiving dinners to shut-ins. Among the saddest images in American culture is that of a fellow citizen with nowhere to go on Thanksgiving, and volunteers often aim to extend a sense of family to people who find themselves alone on the holiday.

***

Thanksgiving is the busiest time of year for those who are in the business of combating hunger—a category that includes the army of volunteers at the Connecticut Food Bank. Four thousand Connecticuters donate their services at the food bank every year. Thousands more volunteer at the more than seven hundred community-based food programs throughout the state that the food bank provisions. The food bank estimates that it provides food for more than half a million meals a year. Similar scenarios play out at Thanksgiving time in every one of the fifty states.

In the week before Thanksgiving, the Connecticut Food Bank’s warehouse in Wallingford is bustling with activity. SUVs and vans line up in the parking lot early in the morning, waiting for their turn to back up to a loading dock and collect the crates of food they have pre-ordered for their soup kitchens and food pantries. Most of the vehicles belong to private citizens who are making a pickup run on behalf of the community or religious organization for which they volunteer. They have emptied out their trunks and back seats to make room for frozen turkeys, sacks of fresh yams, and boxes jammed with canned cranberry sauce, gravy, corn, and the other traditional fixings of Thanksgiving dinner.

Over at the long corridor known in-house as Produce Alley, another source of Thanksgiving generosity is on display in the form of yams. A close examination of the traditional holiday side dish reveals that these yams—there is no way to put this politely—are uglier than the ones you are likely to encounter at your local supermarket. They are too big, too small, or too misshapen for the retail market, which is why they ended up at the food bank. Yam growers in the South donated their rejects to a national feeding program that in turn shipped them off to food banks around the country. Similarly, apple growers in Connecticut have donated boxes of apples.

But it is the story of the birds that best illustrates the extent and variety of Thanksgiving generosity. The birds, of course, are turkeys. The Connecticut Food Bank gives away twenty thousand frozen turkeys at Thanksgiving time, and the staff begins lining up donations in the summer. Some of the turkeys come from in-house philanthropy programs at local businesses and nonprofits. The employees at Waterbury Hospital, for example, donate three hundred birds. Subway has a program whereby employees at the more than three hundred Subway locations in Connecticut can decline their annual gift of a Thanksgiving turkey and give it instead to the Connecticut Food Bank. A local supermarket chain donates one thousand turkeys.

“Thanksgiving is all about the bountiful table,” said Paul Shipman, an executive at the Connecticut Food Bank. The food bank’s chief goal is to provide Thanksgiving dinners for people who might not otherwise be part of the celebration, “but we also want to provide an opportunity for people to help.” Helping, too, is part of what Thanksgiving is about—and a way of giving thanks for what you have.

***

Sarah Josepha Hale hoped to see the celebration of the American Thanksgiving spread to the four corners of the world one day. That hasn’t happened. Instead, two other days associated with the holiday have gone global: Black Friday and Giving Tuesday.

Retailers worldwide participate in Black Friday, which is almost as well known in Brazil and Bulgaria as it is in the United States—though if you asked a Brazilian or a Bulgarian what holiday preceded Black Friday, you would be met with blank stares. Outside the United States, Black Friday takes place outside the context of Thanksgiving.

In many countries, as in the United States, Black Friday is the unofficial start of the Christmas shopping season and a day when retailers offer great deals in stores and online. In the United States, stores open early on Black Friday, and some even open the night before, to the dismay of traditionalists who want to keep the Thanksgiving holiday free of commercial activity.

Black Friday gets a bad rap. A popular view is that Black Friday is the anti-Thanksgiving—that it is all about getting, not giving. After a day devoted to the virtue of gratitude, Americans give in to a frenzy of consumerism and the vice of greed. Or so say Black Friday’s detractors. But that isn’t the full picture. In a free-market economy, getting and giving are connected. A strong economy—as reflected by strong sales on Black Friday—means that more Americans have jobs, higher incomes, and greater means to take care of themselves and extend generosity to the less fortunate.

***

Which brings us to Giving Tuesday, often known by its Twitter handle, #GivingTuesday. In contrast to Black Friday, Giving Tuesday is directly related to the spirit of Thanksgiving.

Giving Tuesday is the brainchild of the 92nd Street Y, a venerable Jewish community and cultural center on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Inaugurated in 2012, Giving Tuesday’s objective is to harness the power of social media to encourage individuals to give to the charities of their choice. The founders selected the Tuesday after Thanksgiving as the day for the annual campaign because of the link between gratitude and generosity.

The idea for Giving Tuesday began with Thanksgiving, according to Henry Timms, executive director of the 92nd Street Y and the principal force behind the creation of Giving Tuesday. “We talked about the holiday, and we saw that we, as Americans, had lost sight of the best and most meaningful things” about it, he said. Timms and his colleagues came up with the idea of adding a new day to the calendar of the extended holiday. “It’s a time when everyone is eating too much and buying too much. We wanted to encourage them to give too much, too,” he said.

Giving Tuesday caught on quickly. The goal was to have one hundred participants in the first year, but more than two thousand five hundred organizations took part, across all fifty states. Three years later, in 2015, Giving Tuesday raised $116.7 million from nearly seven hundred thousand donors at ten thousand participating organizations. That same year, Giving Tuesday had partners in seventy-one countries, where the idea resonates on its own, with no connection to the American Thanksgiving holiday. “We originally thought Giving Tuesday only made sense in the context of Thanksgiving,” Timms said. “We were wrong.”

America’s Thanksgiving holiday may not be observed overseas, but the Thanksgiving spirit is catching on worldwide.

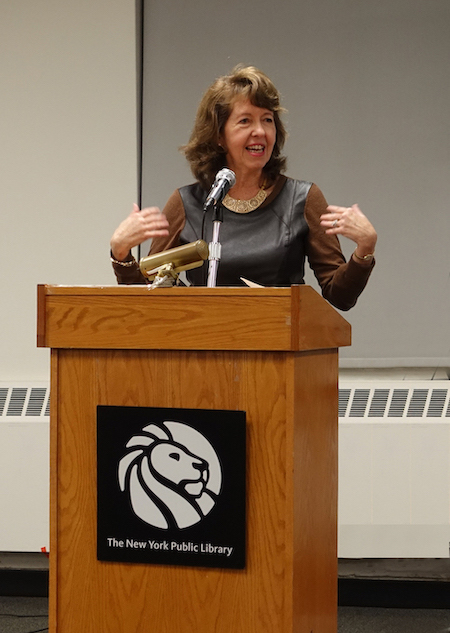

About Melanie Kirkpatrick

Melanie Kirkpatrick is an award-winning journalist and writer. She received the 2001 Mary Morgan Hewett Award for Women in Journalism. The annual award recognizes a female journalist who has demonstrated commitment, hard work, and excellence throughout her career. Ms. Kirkpatrick is also a commentator on the subjects of North Korea and Thanksgiving, to which she dedicated her two published books, Escape from North Korea: The Untold Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad, named 2013 Book of the Year by World magazine, and Thanksgiving: The Holiday at the Heart of the American Experience.

Melanie is also a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and of the Human Freedom Advisory Council of the George W. Bush Institute, and a trustee emerita of the Princeton in Asia program. She has been a board member of the America for Bulgaria Foundation since 2009.

Read our interview with Melanie Kirkpatrick about the changes in journalism in the past fifty years, her experience covering Asia for the Wall Street Journal, and ABF’s efforts to support independent journalism in Bulgaria.