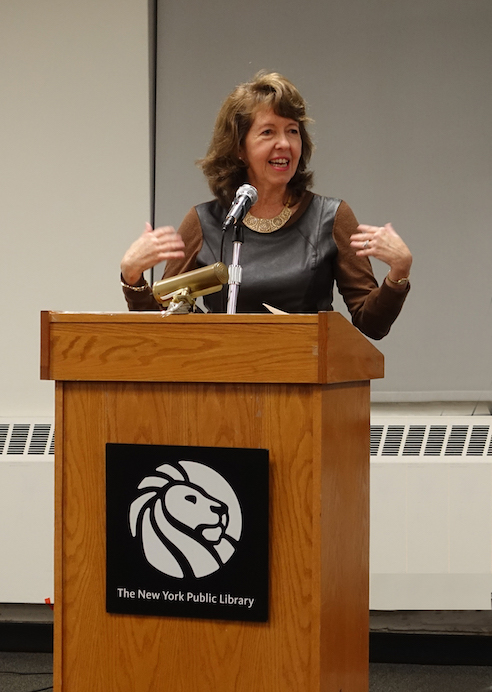

Her first editor at the Buffalo Courier-Express told her she didn’t have the personality to be a journalist; he had thought her too well-mannered, too ladylike. Not only did Melanie Kirkpatrick prove him wrong, but she also became a top journalist and editor at the United States’ highest-circulation newspaper, The Wall Street Journal, where she covered, among other things, two of the most important economic stories of the day—the rise of the Asian Tigers and the opening of the Chinese economy in the 1980s.

“Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg has been quoted as saying that her mother taught her always to be ‘ladylike.’ So did my mother. Also like, I think, RBG, my parents taught me that I could succeed at whatever challenge I took on. There were no gender barriers in our household. Journalism can be a rough-and-tumble profession, and I vowed to do my job, be tough when needed, but not lose my femininity. I’d like to think I succeeded,” says Melanie, who is invariably polite, her words carefully chosen, her articulation perfect.

Staying true to herself, she has notched up many successes. She became a minor celebrity in 1970s Japan, where she appeared in a TV program for English learners. Schoolchildren often recognized her in the street, greeting her with a gleeful, Japanese-inflected “This is a pen!”—the opening line of the textbook used in the program.

A trailblazer in the truest sense of the word, she’s been the only woman, or one of a handful, in classrooms, newsrooms, and boardrooms. She graduated from Princeton University’s first co-ed class, the class of 1973, only 17% of whom were women. In many classes there she was the only woman. The Japanese considered her an oddity: in the early 1970s, she was a professional woman in a country that hired women only as “office ladies.” She was often asked what her parents thought about her leaving home to work abroad. Later, at the Journal, she was among the first women to be included on the masthead’s list of top editors. In 2009, she became the first female board member of the America for Bulgaria Foundation.

Melanie received the 2001 Mary Morgan Hewett Award for Women in Journalism. The annual award recognizes a female journalist who has demonstrated commitment, hard work, and excellence throughout her career. Today, in addition to her continuing engagement with ABF, Melanie is a commentator on the subjects of North Korea and Thanksgiving, to which she dedicated her two published books, Escape from North Korea: The Untold Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad, which World magazine named its 2013 Book of the Year, and Thanksgiving: The Holiday at the Heart of the American Experience.

Another trailblazing woman, Sarah Josepha Hale, is the subject of Melanie’s latest book project. The nineteenth-century writer and advocate of education for women was editor of the most popular magazine in the first half of the nineteenth century. Hale wrote the popular nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and campaigned for Thanksgiving as a national holiday.

Melanie is also a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and of the Human Freedom Advisory Council of the George W. Bush Institute, and a trustee emerita of the Princeton in Asia program.

In this interview for the ABF newsletter, Melanie Kirkpatrick talks about the changes in journalism in the past fifty years, her experience covering Asia for the Wall Street Journal, and ABF’s efforts to support independent journalism in Bulgaria.

Journalism is very different today than it was in the 1970s, when you were starting out. What do you consider to be the most considerable changes in the field?

When I started out, there used to be a real divide between print and other media. Now a journalist is expected to be fluent in a lot of different means of communication. It is not unusual for a reporter to finish a story and submit it to his editor, then go and do a TV or a radio spot on the subject, and then come back to his desk and do some kind of online interactive communication with readers.

If you were a newspaper journalist [50 years ago], after you filed your story, you would just wait for the editor to OK it, answer his questions, and then you could put your coat on and go home. Nowadays, the deadlines never cease. They are 24 hours a day. If something happens, you have to go on air if you are a TV or radio journalist and update readers. If you are a print journalist, you have to write something for media posting on the paper’s website. It’s always been a problem to manage deadlines, but now that you have constant deadlines, it brings a whole different way of thinking to one’s job.

How has the internet changed journalism?

Today, people don’t turn to newspapers as their first source of information. They have already learned the basics of a story from the radio or television or online. Because of their ability to inform themselves [from different sources] readers are much more critical than they were in the past. I think this is mostly a positive thing as it provides accountability.

[However], newspapers have lost advertising [to internet sources] and are having a hard time finding other sources of income. Subscriptions and news stand sales don’t cover the costs that newspapers have producing their papers, not to mention the reporters and editors. As a result, the newspapers often reduce their staff and cover things less well. Then they lose readers. It’s really challenging.

Regional journalism has disappeared in many communities in America [as a result], and in others it has been scaled back considerably. There is also a lack of competition, and this has also had a damaging effect on American journalism. It used to be that every city in America had at least two newspapers, and they were competing against each other for subscribers and for getting the best stories. Now a city is lucky if it has one.

Any promising solutions that have been tried in the United States?

Many of the quality newspapers now charge for access. The Journal was the first to do this. It was heavily criticized for putting up a paywall, for not giving away its news. But we did that early on, and this move told readers, “Look, our content is valuable. We are not going to give it away.” It was harder for newspapers that were giving away their content to, years later, say, “Oh, by the way, now we want you to pay for it.”

What about foundation support?

The Lenfest Institute in Philadelphia is one example. It provides funding for a group of media organizations in the state of Pennsylvania to join together in a single bureau in the state capital to cover state government in a way that no individual organization has the resources to do any longer. That’s a very interesting model. ProPublica is another nonprofit that partners with media organizations to do in-depth reports. Those are two organizations that represent a trend that’s positive. However, the best scenario is that it provides a bridge until media companies figure out how to make money again.

This is similar to ABF’s support for independent journalism in Bulgaria, particularly its backing of regional platforms such as Za istinata. Why is this support important, and how does it help private-sector development, ABF’s core mission?

One of the essentials for business success is access to reliable information. Our programs tend to focus on business and economics journalism. That’s a specialized area that needs specialized training—for example, how to read a balance sheet or understand economic principles or know enough about business to know the kinds of questions you need to ask. A journalist can’t know everything. But he needs to know what he doesn’t know, and find sources that he can rely on to fill the gaps in his knowledge. Many of the trainings we do and the organizations we support are helping improve business journalism in Bulgaria.

We are also helping to fund local journalism so that readers can be better informed about their own communities and how national policies impact them. This is essential for a healthy business environment. If people who are making business decisions don’t have accurate information, they are going to make bad decisions.

At the Foundation, we’ve supported fellowships [such as the WPI fellowship] to send Bulgarian journalists to America. This has been a very positive thing. Bulgarians are interested in what’s happening in America. But it’s hard to cover a foreign country if you’ve never even been there, you don’t have a set of sources, and you don’t know what the cultural content of an article might be.

How did you become interested in Bulgaria and the work of ABF?

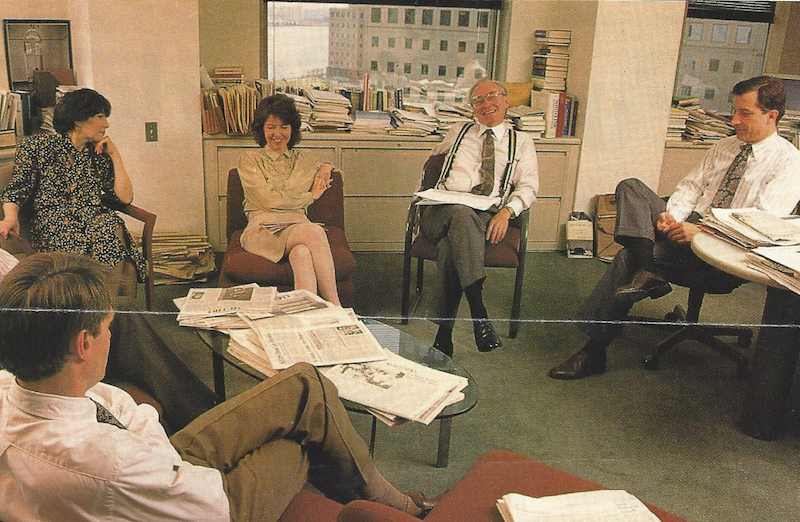

I was the first person on the board who didn’t come out of the business or financial world. The Foundation had just started, and they were looking for someone to bring a different perspective. Bulgaria was a new country for me—though I had spent 10 years in Asia and covered developing economies. At the Journal, I had written or edited editorials about Bulgaria’s flat tax and about Bulgaria’s currency board. In the early 1990s, we had a very memorable editorial board meeting with former Bulgarian prime minister Philip Dimitrov. It was a powerful meeting. He was so eloquent on the subject of the national psyche coming out of communism and into a freer society that we asked him to write an article for us.

If you had to write the story of ABF, what would you choose to focus on? What is the outstanding value of this organization?

The foundation is about empowering Bulgarians. We are not here to impose a model or a way of thinking, but we do value individual liberty, the rule of law, freedom of thought and speech. Bulgarians value that too. But journalism in every free society is on the rocks right now. I see our support of journalism organizations and journalism education in Bulgaria as a way to help Bulgarians to improve their media and do the kinds of stories that will empower the Bulgarian people to start or grow their businesses and be successful at their work.

What have been some of the most empowering events in your own work as a journalist?

Being thrown into the environment of Hong Kong early on in my career was very educational because I was with a small group of very smart people—writers, editors—and we were covering a great story, the rise of Asia. China was just beginning to open its economy. When I first went to China, everyone was wearing gray Mao suits, and by the time I left, you could see colorful western clothing all over the place… I felt really privileged to be there at that time.

Your book about North Korea is based on reporting you started doing in the 1980s. You traveled extensively throughout the region, so why write about the one country that you haven’t actually visited?

I became interested in the subject of North Korea in the early 1980s. I was the op-ed editor of the Asian edition of the Wall Street Journal. An article crossed my desk, submitted by an Italian journalist based in Peking, what we now call Beijing. He got a rare visa to visit North Korea for a week and submitted an article to us about his experiences. I was really blown away by that. It was terrifying but also fascinating… the worship of the Kim family in North Korea. I particularly remember the last line of his article: “I got off the plane in Peking and kissed the ground, happy to be back in a free country.” This was China in the ’80s, not a free country by any stretch of the imagination, but compared to North Korea, it was.

Sometime in the early 2000s, I began to write reports and editorials and opinion pieces on what was happening in North Korea… [The book] was a way I thought I could add value to the discussion.

You interviewed many escapees for Escape. What stories stand out for you?

I had a fantastic interview with a pianist who had been sent to study in Moscow because he was so good, and while there, he was exposed to jazz, which is illegal in North Korea. He came back and was caught playing jazz, and he knew his number was up, so he left.

Most of the people who leave are ordinary people and their reasons are mixed. In the late 90s and through the 2000s, people fled to China, tens of thousands of them, maybe hundreds of thousands, because they were starving and looking for food. There are people, especially those who were living in the North, near the border with China, who had heard about how well the people in China were living, even in northeastern China, which is not the richest part of the country by any stretch, but it was a paradise compared to North Korea. A teenage boy I interviewed who came to America was influenced by the movie Rocky; he was hiding in China and he had a vivid memory of the scene where Rocky opens the refrigerator in his kitchen, and it’s filled with food… That image stuck with this kid because it helped to change what he’d been taught about America.

I was interviewing some North Koreans in Rochester, New York, in the living room in their apartment. At one point in the conversation, the father pointed to a photograph hanging on the wall, a photo of family and friends. He said, “In North Korea, I would not be allowed to have that picture on the wall. I was required to have a picture of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong-il.”

This sounds really grim… Anything positive to emerge out of your research on North Korea?

The heartening thing I’ve learned through my reporting, over the past 20 years, is that there have been networks that have developed that get information into North Korea in a way that didn’t use to be possible. At first, North Koreans who fled to China would hire some Chinese person who could slip across the border and deliver a verbal message to their families. Nowadays, it is much more sophisticated. There is a big trade in sneaking flash drives across the border and the title of the chapter in my book on the subject is “Information Invasion.” The information people are learning about the outside world is transforming North Korea. [It] is showing them how their own leaders have been lying to them for decades. The lie in North Korea had long been that South Korea was poorer than the North and the people were terribly oppressed. But then if you have the ability to watch a South Korean soap opera, you will see how South Koreans live. They sit down to dinner, the table is laden with food, and they go out and get into their own private car. Private cars don’t exist in North Korea. It’s hard to find food in a lot of places in North Korea. So, this kind of information is really having a transformational effect.

So, information cannot be controlled completely, even in a totalitarian state like North Korea…?

The Kim regime has tried to completely shut down the flow of information into North Korea. For example, there are estimated to be only about 1,000 users of the internet. That said, even though many more North Koreans are reading or viewing contraband information, they are unlikely to try to overthrow the regime for the simple fact that the government is so brutal. If you are caught with contraband flash drives, DVDs, or radio that has been altered to receive signal from outside North Korea, the whole family can be sent to a prison camp. That’s a huge deterrent for anyone who is contemplating resistance.

If you can control what information people get, you have a shot at controlling what they think. You can manipulate the information to your advantage.

We in the West have a new kind of problem when it comes to information and the media, which is that we have so much available to us right at our fingertips that it’s overwhelming. The media outlets haven’t caught up. We are experimenting with new models. Right now, in America, media are among the least respected organizations. That’s very distressing because a vibrant democracy needs honest and professional media.

What lessons can we learn from North Korean escapees about our own societies?

The lesson is: freedom comes naturally. It’s in the human heart to want to be free. It can’t always be quelled. There are people who are willing to gamble with their lives to obtain freedom.