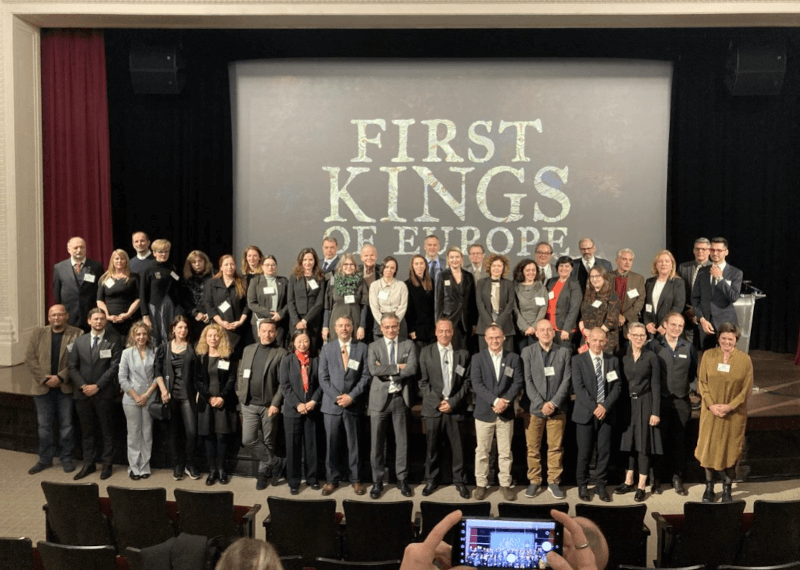

Europe’s first kings and queens come to life in the First Kings of Europe exhibition through compelling storytelling, skillful use of multimedia, and more than 700 artifacts from the collections of 26 museums in 11 Southeastern European countries — an unprecedented international collaboration.

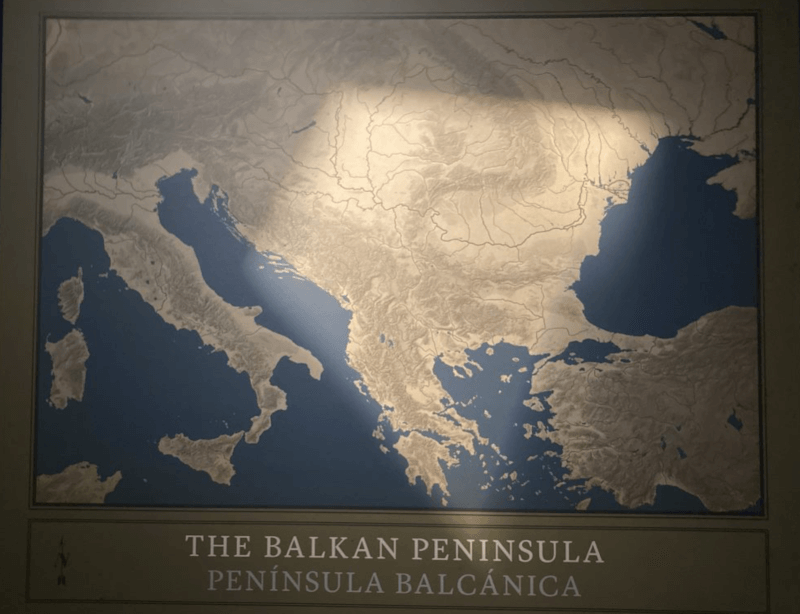

The Renaissance spurred interest in the study of Antiquity, catapulting ancient Greeks and Romans to historic stardom. But they were far from the period’s only superstars: the inhabitants of the ancient Balkans played no less prominent a role in shaping the course of humanity.

Anthropologists Attila Gyucha and William Parkinson have set out to redeem the region’s place in world history. The First Kings of Europe exhibition, which opened at Chicago’s Field Museum on March 31 and is co-curated by the two scholars, is a major step in that direction.

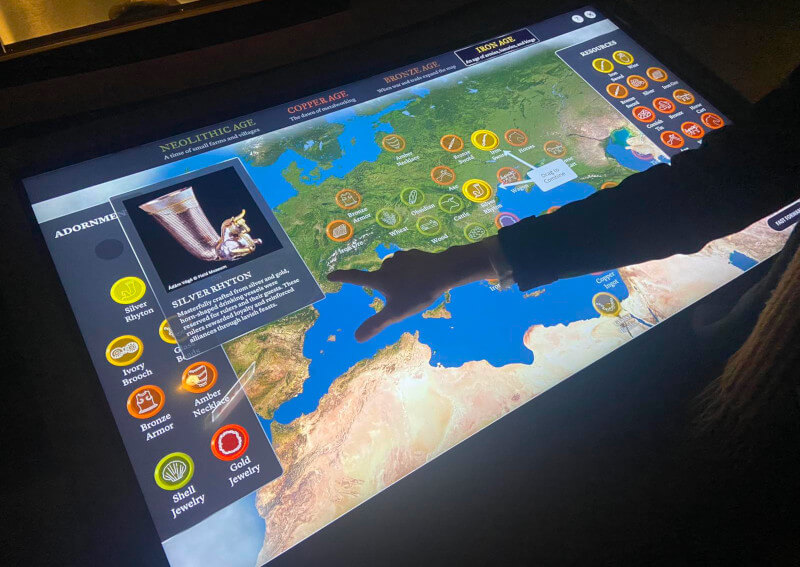

The exhibition traces how once-egalitarian farming communities developed power and hierarchy over time. Visitors travel back 7000 years to uncover the technological and social innovations that transformed these communities into some of the continent’s first kingdoms. By showcasing the achievements of the Balkans’ earliest societies, First Kings also emphasizes the region’s shared heritage.

First Kings of Europe ends with an iconic piece from the National History Museum in Sofia — an intricately crafted gold crown that is so like modern symbols of royal power it makes one wonder: Just how similar to the ancients are we, and what lessons can we learn from them?

We talked to Attila Gyucha and William Parkinson to find out.

Attila Gyucha is an assistant professor of archeology at the University of Georgia, and William Parkinson is a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and curator of anthropology at the Field Museum. The two are co-directors of the Körös Regional Archaeological Project, an international research initiative focused on the Great Hungarian Plain. They have researched many of the themes highlighted in First Kings of Europe their entire professional lives.

America for Bulgaria Foundation: First Kings is an incredibly ambitious project, in terms of both thematic scope and international participation. How did the exhibition come together?

William Parkinson: I have run projects in Greece and Hungary. I worked in Bulgaria and Serbia as a graduate student. Both Attila and I have worked in Albania. We have always had an interest in the broader region, and our research for the last 25 years has concentrated on the question: Once you have small farming villages in the Neolithic, what happens next? Why did some societies get big and complicated, and why did others cycle between getting bigger and smaller? This is really what has underpinned the basic anthropological question of the work that we have been doing.

While Attila and I knew the grander narrative, the story that we wanted to tell, we wanted to do it more collaboratively. That really made it a much better story. Because the scholars from Southeastern Europe we were working with actually had input into the story — into the way we were telling their story. This is a big deal, especially for me. I am not from the region. I am not telling your story for you. When we are working with people, and they are helping us tell the story the way they want to tell it, it works much better.

Attila Gyucha: When it comes to the evolution of social hierarchy and social differentiation, we knew the fantastic richness of the archeological heritage of Southeastern Europe. You have egalitarian societies that shared power and resources in the Neolithic period. Then, at the other end, are these iconic artifacts from the Iron Age — such as princely graves from the Central Balkans or Thracian burials — showing massive wealth and power disparities. So, the artifacts that would tell the best stories were already there — magnificent objects talking about equality and about the other end, the crazy disparities of power among people.

We already knew a lot of the artifacts we wanted for the exhibition because we are geeks. But we still needed to travel — to visit museums, exhibitions, and storage rooms to fill the gaps in our knowledge about the prehistory of the region. And not just to fill these gaps, but to start discussing our ideas with our local colleagues. We also wanted to establish actual relationships with the museums as institutions; we didn’t want to just ask for artifacts.

ABF: Judging by the result, most museums were supportive of the project. Did anyone question your idea? What did it actually take to make this exhibition happen?

Attila Gyucha: When we first visited places, people would say, “Yeah, that’s overly ambitious.” That’s the minimum we got. Some people thought the idea was impossible to accomplish. Of course, it was a crazy initiative considering its complexity! But most of our colleagues were already aware of our long-term work in Hungary, so they trusted us. No one challenged the narrative. Many wanted to add to it, with great ideas and with this object or that.

There were also limitations because when it comes to the availability of artifacts, there are different policies. Some countries were like, “Whatever you see in our permanent exhibition is yours. Because it is such a good idea, take it.” In other cases, they were like: “I am sorry, we just built a permanent exhibition. Let’s go to storage and see what other objects could be used for your exhibition.”

ABF: This collaboration and the focus on the region’s shared past are a refreshing change from the sometimes fractious relationships between Southeastern European countries today. Was the emphasis on partnership and common heritage intentional?

William Parkinson: Absolutely. In the Balkans, there is always a focus on fragmentation, on differences — linguistic, religious, ethnic differences. When people in North America think of the Balkans, they think of that fragmentation. They don’t think of it as a place that has a shared common past. In the exhibition, we don’t want to talk about the modern countries’ boundaries. They are completely irrelevant to the story we are telling. To focus on those modern boundaries will take you away from the point of the exhibition, which is to look at the whole region and for people — whether they are Bulgarian, Serbian, or Kosovar — to recognize: it wasn’t always this way.

For us, a big part of this is also getting the Balkans on the map.

Attila Gyucha: We share a lot throughout the region. There are of course regional specifics, but, as a whole, the region shares the same history, the same trajectory. That’s a really important message.

ABF: You mentioned getting the Balkans on the map. Does that include asserting the region’s significance in Antiquity, a period more familiar to North American audiences through the accomplishments of the ancient Greeks and Romans?

Attila Gyucha: One of the things that were so important in building this exhibition was to show that these ancient cultures across Southeastern Europe were as cool as the Greek story. And it’s a very important thing Balkan people should be really proud of. We also have this other project we are working on, titled “The Oxford Handbook of Balkan Prehistory,” that will expand on the First Kings of Europe exhibition to create a volume for scholars and educators across the world acknowledging the impactful early millennia of Balkan history.

William Parkinson: Not to diminish the importance of ancient Greece and Rome, but the only reason those two cultures are held in such high regard in the Western world is because of the Renaissance. It is a very specific historical moment that generated renewed interest specifically in Greek and Roman culture, which really promoted them as the ancestors to democracy. But the world was a lot more complicated than that. Because there has been such a focus on Greek and Roman culture, many of these other amazing cultures never got talked about. When you add to that the more recent historical and political differences in the Balkans, you never really see a synthesis of that part of the world. This is the first synthesis of Balkan prehistory.

The book that we edited for the exhibition, First Kings of Europe: From Farmers to Rulers in Prehistoric Southeastern Europe, was written by scholars from the region primarily for the general public. I think it’s going to be the textbook for teaching this part of the world for years.

ABF: Can ancient Balkan civilizations tell us something about our own world?

William Parkinson: When I do exhibitions, my goal is to have people see a little differently and understand their own world a little differently. The ultimate goal for this show is to understand that this very unequal world that we live in, and that we know through kings and queens, wasn’t always that way.

The next one is to challenge people’s ideas about the fact that these are all separate countries and to assert that there is a common past. These modern countries that we see in the world, these modern languages, are all recent.

Attila Gyucha: A project like this could really facilitate further collaborations. That’s a first potential milestone in the process of understanding each other better. If you can include 26 museums from all of the 11 countries of Southeastern Europe, other similar projects, in any field, are also possible. Yes, you will have to be patient, you will have to be persistent, it will take a lot of work and time — but it is totally worth it. I honestly believe in this. Eventually, it’s a matter of dedication.

First Kings will be in Chicago through January 2024 and in Quebec between February 2024 and January 2025.

The Bulgarian artifacts’ participation in the exhibition was supported by the America for Bulgaria Foundation. Artifacts from the National History Museum in Sofia, the Regional History Museum in Ruse, and the Varna Regional Museum of History are key parts of the exhibition.