He pivots and bounce passes the ball as skillfully as he turns a phrase. Ivo Ivanov is just as well known for his moving storytelling as his achievements on the basketball court.

On Sunday, June 18, the Kansas-based Bulgarian writer and basketball coach extraordinaire will lend his considerable talents in support of another activity dear to his heart—helping others. He will lead basketball enthusiasts and literature buffs alike in a charity basketball game dedicated to supporting the Festival for Arts and Rights Civic Alarm Clock. An initiative of the Bulgarian Center for Not-for-Profit Law, the festival celebrates civic engagement and recognizes artists reflecting on the power of empathy and mutual aid.

Ivo Ivanov’s own work often immortalizes acts of caring and collaboration. A 2014 article of his comparing basketball team sensation San Antonio Spurs and the Dutch symphony orchestra Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra sums up the writer’s thoughts on why we human beings are at our best when we accept each other’s differences and work together.

“The San Antonio Spurs and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra are not simply a team and a philharmonic—they are civic models for the future… They are two organizations with visionary strategies, organizations that perceive the world as a global village where success is possible only when you have freed yourself from the fossils of prejudice. They have realized every goal is attainable through mutual support, dedication, and collective effort.”

In an interview for the America for Bulgaria Foundation’s monthly newsletter, we talked to Ivo Ivanov about solidarity and empathy, about the similarities between art and sport, about his latest book, A Chronicle of Pain, and about the people and things that inspire him and give him hope for the future.

America for Bulgaria Foundation: What prompted you to support the Arts and Rights Festival Civic Alarm Clock of the Bulgarian Center for Not-for-Profit Law?

Ivo Ivanov: My contribution to the campaign is a basketball practice and a game, combining two things I love—basketball and social engagement. I am always looking for ways to encourage people to be more socially active. We often fall into a closed cycle—work, grocery store, home, work, grocery store, home—and lose contact with the things that truly matter and that could help us leave a mark. I have always believed that a person becomes useful to themselves when they become useful to others. Ultimately, a person feels more fulfilled when they help others, when they manage to strike those chords that make a society better, more humane.

ABF: They say that art makes us more considerate. In this sense, can we argue that art is socially engaged by definition?

Ivo Ivanov: Artistic creation is often socially engaged even when it does not appear so. Let’s take Monet’s water lilies, for example. We look at a work of art and see nature. We see harmony, beauty, colors, and impressions and conclude that it reflects something beautiful in nature, and often it does. But, at times, there is something else beneath the surface.

Claude Monet, at a rather advanced age, isolated himself in his home in Giverny. During World War I, soldiers bound for the slaughter marched by his house. The elderly Monet watched those young men with sadness and suffered. Somehow, in spite of his suffering and the war, he decided to create a garden in his backyard with a pond filled with water lilies. And in the water lilies, he tried to find solace and a refuge from the horrors of war. Looking at his astonishing paintings, one senses that they are a special kind of protest, of the most pacifist kind. His response to the bloodshed, cruelty, and barbarism of a senseless war was beauty.

You sometimes find socially engaged art where you least expect it… And sometimes it is what wakes society up.

ABF: Your stories are incredibly life-affirming and permeated with a belief in good and in humanity’s ability to elevate itself through acts of kindness and selflessness. What sustains this belief?

Ivo Ivanov: It is an empirically grounded belief that comes from years of observation. I have encountered so many people, so many life stories. Some of them are marked by pain and bitterness. Some people have plenty of reasons to be disillusioned with humanity and life, yet they find within themselves the need to be kind, to believe in people, in the future, in good.

In recent years, we’ve had many reasons for disenchantment. We have polarization, intense polarization unlike anything we have seen perhaps since World War II. We have rampant hatred. Increasingly, social media is destroying the connections between us, dividing instead of uniting us. We have a war in Europe’s backyard, dictatorships, inflation, a pandemic, unemployment, skyrocketing prices, automation taking away more and more jobs, and so on. We have so many reasons to worry about the future of humanity.

At the same time, we are children of the 20th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, life expectancy was 46 years. We used to die of acute tonsilitis, crossing the Atlantic Ocean took three months, humanity faced incredible unemployment and colossal inflation, suffered from numerous diseases, and experienced two devastating world wars. Death, suffering, and wars were an everyday occurrence worldwide. Sometimes, we need to take a step back and put things in perspective.

The media doesn’t pay attention to positive news, but I assure you there is more good news out there than bad news. Negative stories get more reactions—more likes and clicks. But if we look closely, we’ll find so many positive news stories. Last year, US scientists carried out the first successful nuclear fusion experiment. This process replicates the processes occurring in the sun’s core, a potentially inexhaustible source of clean energy. Japanese scientists managed to isolate bacteria that feed on plastic, which may clear our oceans of the horrifying pollution with microplastics. We have many, many reasons for optimism. I am optimistic about artificial intelligence as well.

What I want to say with these examples is that humanity is moving in the right direction. We may not notice it, but if we compare the state of the planet now to the way it was 20, 30, 40 years ago, we will observe undeniable progress. It may be slow, there may be retrograde forces trying to halt this progress, but it cannot be stopped.

ABF: Humanity faces many challenges, as you pointed out, but the pandemic undoubtedly stands out among them. How did you weather this ordeal as a person and a creator?

Ivo Ivanov: The pandemic gave me a lot of hope for the future of humanity. I saw kindness the likes of which I hadn’t seen in a long time. I saw collaboration between people that I didn’t think was still possible. I saw people giving concerts on the roofs of their houses, on their balconies. I saw people hanging out in front of hospitals and nursing homes to be with relatives who were unable to go out and see their loved ones. I saw people playing music and dancing underneath their loved ones’ windows to provide comfort and entertainment. I saw so much kindness all around me.

An elderly farmer from my home state of Kansas sent a letter to former New York governor Andrew Cuomo, which Cuomo read on television. In the letter, this old man told his story—that his wife had been very ill and bedbound for years and that he had to work in his old age to support them. He wrote that he didn’t have much money, but he was sending two masks because he saw that there was a great shortage of masks and an awful lot of sick people in New York…

Most people responded to the pandemic in the kindest way possible: they showed empathy and compassion; they provided help. This gave me great hope.

Suffering usually produces the best art. Without suffering, there would be no Crime and Punishment; there would be no Dostoyevsky at all. There would be no Franz Kafka, and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica would not exist.

The pandemic has given us many works of art. I think Georgi Gospodinov’s Time Shelter, or at least a part of it, was written during the pandemic. Many people wrote books during the pandemic. The pandemic may have robbed them of a part of their livelihoods, but it gave them the time they needed to write their big book, paint a great painting, or compose their magnum opus.

ABF: Your book A Chronicle of Pain came out in 2022. Was it also born out of the pandemic?

Ivo Ivanov: This book was the product of five years of work, in which there were moments of despair because of the polarization I mentioned. This rift between left and right, blue and red, young and old, men and women, began to get to me. That said, in almost every one of these stories, I tried to find a resource for kindness within the pain and the suffering.

Suffering and pain become a part of every person’s life sooner or later, such as with the loss of a loved one. Illness sometimes becomes a constant companion. You are disappointed in some people and encounter betrayal. At that moment, you must be prepared, you must know how to react. The best swimmers drown when they panic. Very often, a catastrophic event can send you into a place of panic and then you can drown, even if you are a good swimmer. Pain can very often be a resource for strength. Many of the people I write about in the book have found a way to turn pain into strength.

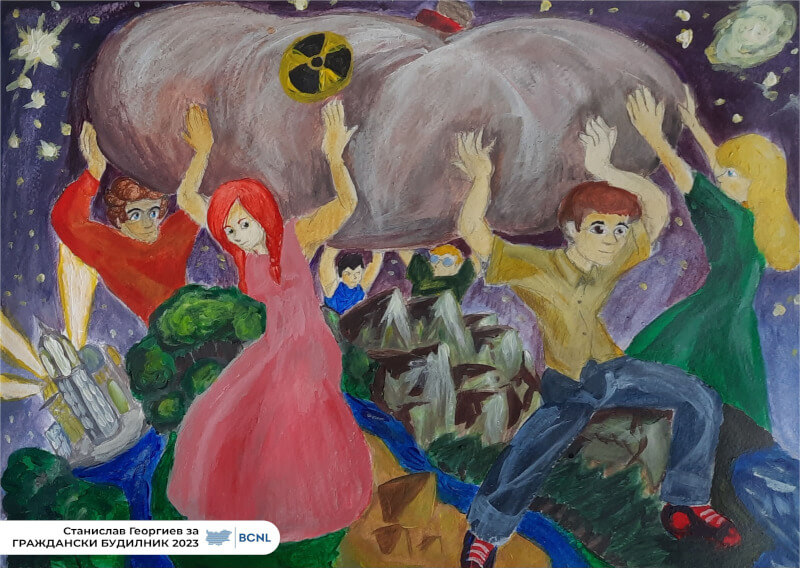

The first story is dedicated to [multi-sport Paralympic athlete] Oksana Masters, born in Ukraine, near Chernobyl, shortly after the 1986 nuclear disaster. Born with multiple defects due to radiation exposure, Oksana was abandoned in an orphanage. She spent her childhood in horrific conditions, robbed of a person’s most important years. And in spite of it all, she managed to turn the pain into great strength.

But a chronicle of pain only becomes a chronicle of strength by choice. This is the book’s message: it is up to you to turn pain into strength, not to panic and drown, and to climb the highest peak instead.

ABF: Speaking of heights, you write inimitably about the pinnacle of global sport, making it accessible to a broad audience. And although you are best known for your sports writing, art features just as frequently in your work and sometimes even alongside sports. How are sport and art connected?

Ivo Ivanov: There is a lot of art in sports. Basketball and music have a lot in common. There are intervals, there is rhythm, there is movement, which is very musical. When five experienced basketball players take the court and are in perfect harmony with each other, they become a musical quintet making chamber music that is a delight for the senses. Maybe not the sense of hearing, but sometimes there is synesthesia, where visual stimuli become musical and musical stimuli become visual. Then, you get some very beautiful compositions on the basketball court.

There can also be sport in music. I was at a concert by Wynton Marsalis, a jazz musician who wrote an elaborate composition dedicated to basketball, in which each part paid homage to a different favorite basketball player of his. Individual parts were passed like a ball—from one instrument to another. There were quick breaks and gradual attacks; his creation was very interesting.

We know that there is an art to the movements of many top athletes. Dimitar Berbatov and Zinedine Zidane were graceful artists on the pitch, making brush strokes with their movements, and they had imagination. There are many athletes who may lack the strength and perhaps the speed, but they have creativity, with which they overpower their opponents because there is an element of unpredictability, as there is in the work of the greatest painters and composers. There is an element of genius there that cannot be anticipated. Sometimes, that happens in sports, too.

Sport and art, in my opinion, are a very good metaphor for life. They are symbolic raw material for every single author. You may look into them and discover an entire life. The Olympic discipline of triple jump, which lasts about ten seconds, contains a whole life—with its disappointments, successes, falls, failures, changes, betrayals, efforts. Most jumpers compete in a single edition of the Olympics in their careers because the discipline involves fast-twitch muscles, and one loses fast-twitch muscle strength very quickly. During the years of preparation that enables them to reach their peak in ten seconds, they endure many deprivations… When you know this, you start looking at an athletic competition with different eyes, no longer seeing merely a person hopping, stepping, and jumping—you see a whole life.

ABF: You have lived more than half your life in the US. What is it like to be a man of two worlds?

Ivo Ivanov: I left with the idea of coming back. I wanted to walk the roads taken by Jack Kerouac, Ken Kesey, John Steinbeck, William Burroughs—my childhood literary idols, absorb American culture, way of life, music, and humor, and then bring all the lessons back to Bulgaria.

That was the idea, but fate had other plans. I met my wife, we had children, and my career took off at a dizzying pace… A year passed by, two, 10, 15, 20. Meanwhile, I found a way to exist simultaneously in both worlds, to be both here and there, to find balance in this dualism, and to function fully in both places.

Learning a new language and embracing a new culture are enriching experiences. That is not to say that my US passport comes first now. My first identity—the Bulgarian one—will never be replaced. Although I have lived more years in the US than in Bulgaria, I will always be, first and foremost, a Bulgarian. I come to Bulgaria every year; I am drawn to my country. The only time I couldn’t come back was in 2020 because the borders were closed, and not being able to return hurt physically. Because here I am myself. Here is my childhood, my character, my parents, my friends, my memories, my first love, etc. You cannot uproot these things from your heart.

At the same time, I have not narrowed my identity and shut myself inside a micro version of Bulgaria in the US. I have opened myself to the American way of life. I am very deeply involved in the fabric of American society. I care about politics and about popular culture. I used to write for a major newspaper in the US, on social issues, etc.

This all goes to show that despite the dichotomy, there is a way to exist in both places, to have two feet in both worlds, and to be a citizen of two places—and perhaps of the whole world.

Borders don’t really matter anymore. Europe is gradually becoming one country; physical borders are beginning to blur. Bulgaria is not so much a territory as a way of thinking, a phenotype, a mentality… Why am I as happy as a child for Georgi Gospodinov, for his award? Why did I cry when he won the Booker Prize? Because there is a logic to taking pride in the successes of our thinkers. A friend told me, “It’s an individual award. Why do you feel proud? You didn’t earn it.” I don’t see it this way. Georgi won the prize for himself, but also for all of us, because if you consider his words closely, you will notice that a part of us is present in his storylines, and this is our mentality, which was also formed here. Georgi was formed here—his thinking, his character, his philosophy. Every person who has lived and grown up here, especially if they are contemporaries of Georgi’s, can find a piece of themselves in his work.

ABF: Please give us a sneak preview: What do you have in store for players and spectators at the charity practice on June 18?

Ivo Ivanov: I want this practice to be an adventure. I won’t be able to teach people a lot of basketball strategy in one practice, but I will show them some things that are only done in the American school as well as moves and tricks of my own invention. I’m going to show them some really neat things to build coordination with a basketball. I also want to help them with something very important, which is underestimated not only in this country, but also in many elite basketball academies, and that is warm-up and flexibility exercises.

We will also put on a show and party. We will have music at the practice and some surprises. I don’t know if people will learn basketball, but they will certainly attend an event they will not forget.