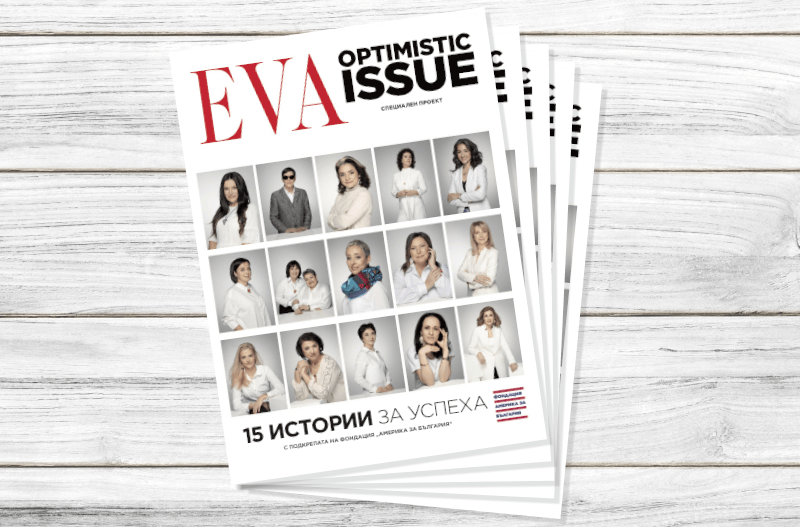

We partnered with Bulgarian lifestyle magazine EVA to present female leaders from the Bulgarian nonprofit and public sectors. The result was EVA’s Optimistic Issue: 15 Stories of Success. This is one of the featured stories, republished with permission.

Text: Irina Ivanova

Photography: Kostadin Krastev-Koko

Translation from Bulgarian: Lika Pishtalova

To many of us, an organization called Bulgarian Institute for Legal Initiatives (BILI) probably bears no relevance to our lives and has nothing to do with our real problems and small daily battles. Bilyana Gyaurova-Wegertseder, BILI’s director and co-founder, proves that the opposite is true by giving the following example: “When you open your fridge, you don’t look for rule of law inside, right? But the fridge and rule of law are closely related. Some time ago, I watched a boy on TV who said he dreamed of becoming a forester because he loved the mountains and wanted to reforest them. That sounds great, but let’s imagine that someone from the so-called ‘timber mafia’ starts illegally cutting down all the trees that the boy has planted. If there are no efficient investigative bodies, this crime will not be properly investigated. If it is properly investigated, but there is no accountable prosecution system, the indictment will not hold up in court. And, finally, if there is no independent court, even the best-formulated indictment will not result in a conviction. This example can be projected to other areas of life, and ultimately it will turn out that the empty fridge has a lot to do with the rule of law in our country.”

Bilyana was born in Ruse and as a schoolgirl participated in the protests against air pollution in her hometown. Back then, she decided she wanted to do something to help combat social injustice, which in the quoted example verged on criminal negligence. After high school, she applied to study both law and journalism. Being admitted to both programs, she chose to study law, hoping that, as a lawyer, she would still have the chance to produce journalistic materials; the opposite would have been more complicated.

Today, Bilyana’s work is related to writing articles for different media. “Besides, law and journalism have something in common, and that is the way in which you ask questions. Both in law and in journalism, it is very important how you ask questions and what questions you ask,” she adds.

Together with a group of colleagues and like-minded people, Bilyana founded the Bulgarian Institute for Legal Initiatives in 2007, shortly after she completed the American Bar Association Program for Central and Eastern Europe, where she worked as a senior legal consultant. Roughly two years later, she and her colleagues were contacted by the America for Bulgaria Foundation (ABF) to kick off an almost 15-year partnership that continues to this day.

In the little free time she has, Bilyana reads books, preferring non-fiction over fiction in the last few years. As a typical representative of the Sagittarius sign, she also likes traveling. Journeys to other worlds and cultures where people communicate differently have an energizing and liberating effect on her. Sometimes, in moments of inspiration, she also likes to write poetry.

Apart from being a law graduate, you also graduated from the Dimi Panitza School of Politics. How exactly does one study politics, and what did you learn there?

It would be difficult to answer these questions within one single interview, but I will give it a try. The valuable thing about the Bulgarian School of Politics was that it gave its trainees the opportunity to meet and communicate with political party members, some of whom had already gained the reputation of successful politicians or civil sector activists. The school provided us with a neutral environment where we could bounce off opinions, ideas, and arguments and take part in a meaningful conversation. Today this is rare. In addition, our graduating class had the unique chance to meet and talk to politicians who had shaped and defined Bulgaria’s political and public life from the beginning of the democratic transition to the present day. I mean politicians like Ahmed Dogan, Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Sergey Stanishev, Georgi Parvanov, etc. What seems to me an important skill to acquire, and what I think is in short supply in our political reality, is the ability to design policies in any sphere of life: the judiciary, economy, education, healthcare, etc. Policymaking requires longer-term planning, the ability to communicate with different groups of people, to listen actively, and to show understanding even when you disagree with other people’s arguments. I think that politicians nowadays don’t have these skills, and this has a negative impact on our political life. Another problem has to do with the fact that politicians take everything too personally. When someone becomes an MP or a cabinet minister, they suddenly get offended by the softest criticism or attack against them. This attitude limits the policy-making horizon and prevents those politicians from making the right decision.

What do you think is the solution to the challenges in our political life? What is the proper way to handle them?

The problems in our political life could be solved through education and prevention. Education is important because educated people have a critical approach to things, and they do not take everything at face value; they are constantly looking for the best solution and are less vulnerable to manipulation. Prevention makes it possible to anticipate problems and find ways to prevent them at an early stage. If you only react to problems, in most cases, it is already too late.

Your CV makes it clear that you are familiar with the American political and legal systems. What are the most important lessons we can learn from these systems?

First of all, Americans are pragmatic. On top of that, they have a very strong sense of belonging to their country, nation, and community. Third, they have self-esteem because they know that the state has their back. We lack all three, especially the second one. It is as if the years of transition have torn apart the fabric of our nation and community. We also lack self-esteem — not “the chest beating” type, but the self-esteem of citizens who come from a country with a centuries-old tradition, a country that has given so much to the world while remaining somehow invisible to it. In America, people feel great respect for the institutions, especially the courts and the judiciary, and the people who represent these institutions and the judges themselves know that they hold these positions to serve the public. I think in Bulgaria it is still the other way round. There are many lessons we can learn, but one of the most important ones is that democracy comes with a set of rules that must be observed by everyone, from the president to the homeless guy on Fifth Avenue.

Which one of your professional achievements brings you the greatest satisfaction?

In the work I do, one has to be patient because it takes time to achieve results; the whole process is gradual, and sometimes you rely on sheer chance. Hence, I am satisfied when I see that a policy that I have worked on for years has been adopted at the institutional level. I am also happy when people seek and appreciate our expertise and experience, even when the view we offer is critical. The role of civil society organizations is not only to observe, assess, and criticize. They can also be a valuable partner capable of offering adequate solutions to problems.

Where do you find the inspiration and optimism to keep working and following your path?

To me, the glass is always half full, and I believe that a solution can be found even in the most complicated situations. I see how generations change, and this will slowly and irreversibly lead to positive developments in our country. This process is inspiring in itself, especially when we draw parallels with communist times. I am also inspired by young people with whom we have been trying to work more intensively in recent years.

How can the Bulgarian Institute for Legal Initiatives help Bulgarian citizens? What does the institute do?

How can the Bulgarian Institute for Legal Initiatives help Bulgarian citizens? What does the institute do?

We work on issues such as implementing judicial reform, counteracting corruption, enforcing the principles of good governance, establishing the rule of law, etc. These are all topics that sound very academic and somehow distant from our everyday lives. But, as in the example of the boy who dreamed of becoming a forester [see the introduction to the interview, ed.], the rule of law has a direct impact on our lives. BILI’s motto is “dare to know.”

In our work, we dare to learn things and seek information that can improve the lives of all citizens in this country. We dare to be the watchdog that keeps institutions on their toes, accountable, and responsible. Recently, we launched a civic education program designed to explain seemingly abstract topics to primary and high school students. I am glad that they show curiosity and ask direct and uncomfortable questions. This gives me hope for the future.

What does your partnership with the America for Bulgaria Foundation (ABF) mean to you?

When we were contacted by ABF almost 15 years ago, the Bulgarian Institute for Legal Initiatives already had its own history and was recognized as one of the leading organizations in the area of judicial reform and fighting corruption. ABF had heard of our work. The Foundation’s mission covered strengthening the democratic institutions in the country through cross-sectoral dialogue, and this was a key element of our work. I have always appreciated ABF’s partnership and trust as positive and sustainable change can only be achieved through joint and well-targeted efforts.

What are you thankful for in 2023, and what do you wish for or expect in 2024?

2023 is not yet over and, so far, it has been a colorful year. I am grateful for each one of its colors, for every new acquaintance, and for every exchange of ideas. My job gives me the opportunity to meet all kinds of people, which is both challenging and enriching. In other cases, it can bring you down to earth. For 2024, in global terms, I wish for stability, predictability, peace, general settling of emotions, and more common sense. On a personal level, apart from health, I wish I could have a bit more free time, opportunities to travel, and multiple reasons to smile.