By Katerina Vasileva

Katerina Vasileva is a graduate of the 2023 class of the America for Bulgaria Foundation’s Media E:volution program.

“Since I can remember, I have been digging into the past.”

With these words, nine months ago, I began a timid two-minute story in the Pecha Kucha format [a Japanese-inspired storytelling technique using few words, ed.]. The story of my interest in the past was the first one I told as part of the Media E:volution fellowship program for young journalists of the America for Bulgaria Foundation. I was honored to be a program fellow over the previous year. To this day, this continues to be the story of my vision of community building, of the transition from “I” to “we.” Of why it’s worth trying to do anything at all, whatever that thing is.

I started doing journalism when I was 18. The reason was simple: I suddenly found a profession that put a premium on a habit of mine that, until then, had been universally reprimanded and annoying to everyone around—asking questions. Out of the millions of questions, the ones about the past have always been the most challenging for me. What was my late Grandma H. like before I was born? What did my great-grandfather do for a living to merit having his gun in a display case at home? And why was my grandfather in prison? Why? Why? Why?

There is something truly intriguing about the quest to learn more about the time before you existed, about the people without whom you wouldn’t be around today. As I inevitably grew older, over the years, my curiosity spilled beyond the boundaries of family, and my questions became “significant,” social, political. Why were there so many wars, migrations, and crises in the last century? What happened during the communist era? Who are the victims of the People’s Court? How did the transition period [the years of post-communism, ed.] come about? Is it over? Why are we the way we are?

In our quest for the past, for ancestral memory, and even for the collective history of a society, we are inevitably alone. I was convinced of this truth, which is why I indulged my greatest interest on my own. I read books on the subject, rummaged through old family documents, and even went on a long, solo trip through the Balkans and Eastern Europe so I could delve deeper.

But the past is shared—especially the recent past, of the last one hundred years. Our most recent past, which still divides us—in both Bulgaria and the Balkans and maybe the whole world. Dealing with this subject on my own likely helps me feel more complete. But it won’t help me contribute to the cause that’s at the heart of learning about the past—uniting the society we live in. Overcoming traumas, divisions, and historical complexes in order to build a community marked by humility, maturity, and a readiness to meet new challenges—this is the true purpose of memory.

With the help of journalism and the Media E:volution program, I gradually opened up to others who were interested in the same questions. Naturally, I started with art, introducing myself and readers to several stories of artists who narrate communism and try to make sense of its legacy through their works—a radio ballet, an exhibition, an art installation, a book, and a film from archival footage.

Then I went back a little further, recalling my Eastern European trip from 2022. On that trip, I visited several wonderful museums that deal with the same painful topic of memory in an innovative way. I managed to get in touch with their creators in Sarajevo, Zagreb, and Warsaw and wrote a story about these special places—about their origins, about where they got support, about whether they were interested in the stories of “ordinary people” as a mirror of collective experiences.

I was also actively exploring the memory theme in current political events, such as the decision to relocate the Monument to the Soviet Army. I looked at the image of this monument beyond history and politics—as a popular meeting place for youth communities, a canvas for expressing a civic stance, a music stage. Is it possible to rethink places like the Soviet monument in a new, democratic light? This article made me realize that many of the questions I am interested in will probably never have an unambiguous answer. And there’s nothing wrong with that.

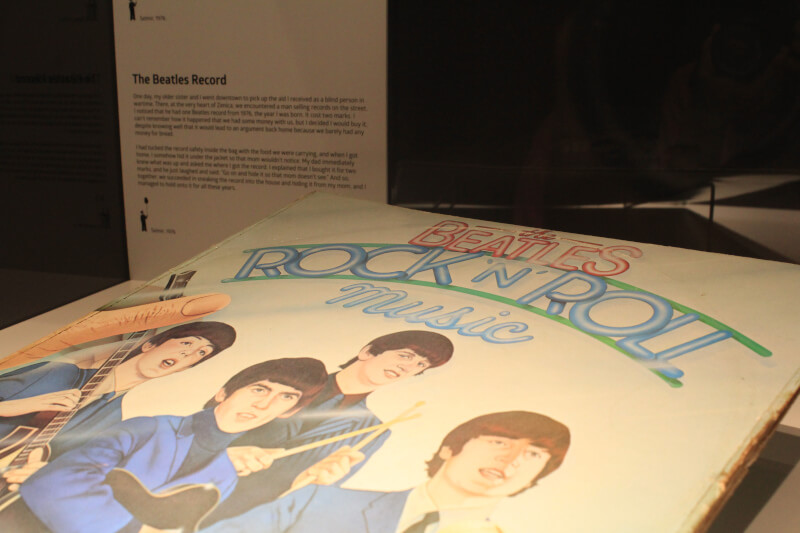

Later, I also created video stories about other small communities engaged in the cultivation of collective memory. The Super 8 Cinema Club, for example, unites fans of amateur cinema who restore and digitize old home videos from Bulgaria. Thus, the club preserves the memory of the life of “ordinary people” in the last century—families at the seaside, children at a state-organized march, young people on the road. “These are separate personal stories, but together they create a full picture of our cultural heritage,” Tihomir, one of the artists, told me. “An image of our history,” he added.

I completed my journey in the program with yet another story about the past—that of the young women behind The Slav Tale exhibition. Through mock-ups of a prefab concrete apartment building and one of the apartments in it, the artists and friends of mine Anna and Kalina confront socialism and democracy in the chaotic years of transition and invite the audience to a dialogue about the legacy of that period. “The past is a big part of us and is the foundation on which we work and grow,” Anna told me at the time.

Meeting all these people—artists, researchers, civil society professionals, and others—convinced me that, although our country has many pressing problems it needs to solve, there is a small but strong community growing inside it that tends to our collective memory. These people consider engagement with the past as integral to any healthy, civically mature, and prosperous society. And they show me that I am not alone in asking myself these questions.

For me, the increasingly frequent invocation of the memory of traumatic events from Bulgaria’s recent past is a sign that we are beginning to understand ourselves a little better, to see more clearly the big picture of causes and consequences. I hope that by taking a step back, by looking back at history and its lessons, we will teach ourselves and future generations how to move forward together—as the diverse, united, and self-confident community I know we are capable of being.