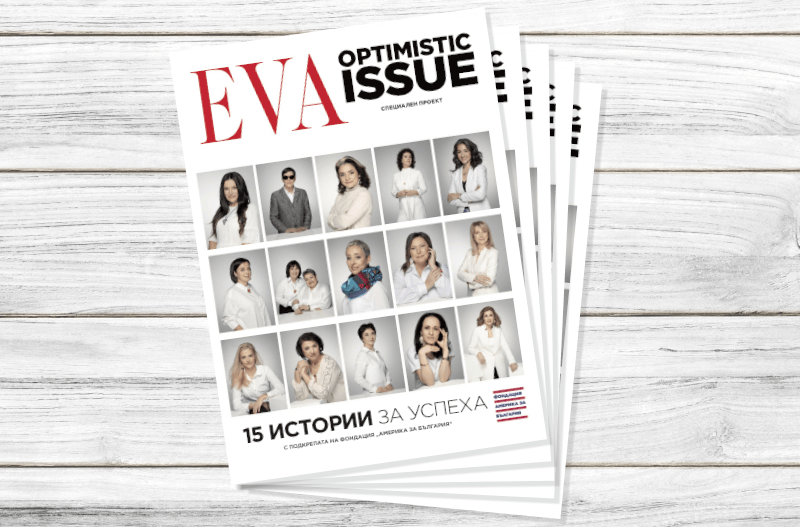

We partnered with Bulgarian lifestyle magazine EVA to present female leaders from the Bulgarian nonprofit and public sectors. The result was EVA’s Optimistic Issue: 15 Stories of Success. This is one of the featured stories, republished with permission.

Text: Theodora Nikolova

Photos: Kostadin Krastev-Koko

Translation from Bulgarian: Ana Blagova

Venelina spent most of her journalistic career at the Bulgarian National Radio (BNR), serving as a correspondent for its national current affairs program in the city of Stara Zagora from 2001 and, for a while, as the managing editor of its regional radio station. She is a recipient of a Panitza Journalism Award for Civil Courage as well as awards from the Office of the National Ombudsman and the Bishop Methodiy Kussev Heritage Foundation. She is also the first recipient of a Red Line Journalism Against Corruption Prize, awarded by the Bulgarian Anti-Corruption Fund Foundation for investigative journalism.

Venelina Popova is an invaluable independent voice in Bulgarian journalism. To seek truth tirelessly, to speak it to any power, and to never back down before the strong of the day — these convictions help her remain independent amid attempts to influence and silence her, she says.

Venelina received threats as a result of her investigations; her apartment was broken into, and she was sued twice, with both cases decided in her favor. I asked her what her work has taught her about people, about those in power, about society, and about herself. Here is what she said.

“Oh, I can write a monograph in response to your question!” she quips. “It’s true, my whole life has been a struggle, from my school years to this very moment. There have been battles, many of them. They have undoubtedly tired me out. Journalism exhausts you, it does not recharge your batteries, or it does so only in the very rare cases when you see that your efforts have not been in vain. I’m not sure what I’ve learned in my 35-year career as a reporter, newswoman, columnist, and, most importantly, in my brief stint as a manager. But I discovered that people and societies are hard to change and that any change must start within ourselves. If we cannot change ourselves, it’s futile to expect it from others. But that — changing yourself and your point of view, leaving your skin, as it were, to step into someone else’s shoes, forgiving, not keeping a grudge, but being generous and kind — that is the hardest thing in the world.”

Nowadays, Venelina Popova writes for the independent online platform Za istinata (“In the name of truth”), owned and published by the nonprofit Pro Veritas. It’s a platform for investigative journalism aiming to support the establishment of a network of investigative journalists around the country. It focuses on problems in all important spheres of life: from economy, politics, and healthcare to education and culture. It hopes to shine a light on corruption and power abuses, but it also aims to tell the success stories of honest people who have the willpower and energy to push society forward.

About six months after her retirement from national public radio, Venelina got a call from her colleague and Pro Veritas founder Spas Spasov, inviting her to write for the platform. At the time, Venelina was a contributor to Toest.bg, but accepted the new invitation as well “because of the thrill to investigate, in addition to writing opinion pieces.”

In the age of “fast” journalism, “fast” writing, and “fast” reading, how does the platform defend the value of investigative journalism, and how does it protect investigative journalists?

My work as a BNR correspondent in Stara Zagora was as exhausting as any reporter’s job — chasing after facts and events, a murder today, a fire, a flood, or a ministerial visit tomorrow… You are always in a rush, and sometimes that rush is completely pointless. Nevertheless, I managed to develop an interest in investigative work. Both cases against me were for investigations aired on the radio. It’s different now because I can devote the necessary time and space to an investigation. I like to follow up on things, which is hard to do when you are on a beat. We have a nice saying in Bulgarian: “A miracle only lasts three days.” This is, more or less, the amount of time that the media will spend covering any event. Za istinata is a website conceived and specifically developed as a platform for investigative journalism, funded by the America for Bulgaria Foundation. Its contributors are not restricted in relation to their investigation subjects, unlike journalists at other publications, which depend on their advertisers and the agendas of their owners or the state (in the case of our so-called public media such as the Bulgarian National Television, the Bulgarian News Agency, and BNR). Since I started working for Za istinata, I hear the occasional unpleasant comment that I’m now “on the American payroll”; in other words, that I’ve sold my integrity. It’s unsettling, but I try to ignore it because I can say with a clear conscience that Spas Spasov, who founded and developed the platform, has never told me what to write.

You are one of about ten journalists writing for the platform. How are the authors selected?

I don’t know Spas’s criteria for choosing the authors, but I can testify to the fact that it is extremely hard for him to find regional journalists who are interested in doing investigative work. Even when there are such people, they are usually employed by a local media dependent on local authorities and businesses. Most of the authors of Za istinata have their own media outlets, and thus they feel free to investigate.

What brought you to journalism — was it fate or personal choice?

Many people like to call the will of God “fate.” Ok, let’s call it that. Up until the removal of the totalitarian government, which was undertaken by high-level apparatchiks and state security officers, I had no interest in journalism, for obvious reasons. I applied for a vacancy in the Stara Zagora regional radio in the fall of 1990. My application was approved, and I was hired, despite the reluctance of then-director Dinko Dinev to hire a “blue,” or an “opposition,” journalist at the station. This happened at the insistence of the chair of the selection committee, journalist Yordan Lozanov, who did not give in to pressure.

You say journalism is your calling. When did you discover it?

You say journalism is your calling. When did you discover it?

Journalism is indeed a calling. You may have graduated in it, but that does not make you a journalist. At the same time, you might have a different background — and it doesn’t even need to be in the humanities — and make an excellent journalist. You need to be open to the world, to be interested in life and people, to experience a constant thrill, and, most importantly, to have the guts to ask the right questions, no matter how high up the food chain the person you are questioning is. If that bothers you and you keep self-censoring, you had better find another field of work. I discovered that this is my calling almost immediately after I started reporting, hosting shows, and delivering news. It didn’t take long for me to feel in my element, and this is perhaps why, only a year after I was hired, the then-deputy director of BNR Ms. Rayna Konstantinova asked me to become the managing editor of Stara Zagora Radio. Ten years on, I took that job again, and I do not regret it, despite paying a heavy price. We succeeded in giving the station a new and modern sound.

What is your response to people who claim that there are multiple truths?

I don’t know. I haven’t had to challenge such a statement, even though there are many traps on the way to the truth: you might be wrong, you might misjudge a person, a circumstance, or a situation, you might lack context. Which is why your moral compass should guide you in your pursuit of the truth. Of course, morals, as a set of ethical rules, is not a dogma, and it does change, but some things will always hold true.

Have you ever told a white lie in your personal life?

Yes, I have, and I still do despite the fact that a lie is always a lie, even when it has a noble purpose. However, there are circumstances in which truth can kill, because we, as human beings, are not prepared to hear it, especially if it is about ourselves. Just think about how easily one says things one believes to be true of others, and how hard it is to face a truth about oneself. This is why tabloid journalism is so unpleasant: it digs into someone’s dirty laundry under the pretense that it’s in the public interest. Journalists must always abstain from personal feelings and attitudes toward the subjects of their criticism.

What gives you the strength and conviction to keep going?

I honestly don’t know. But if I’m still around, then I must be here for a reason. I must have things to accomplish, so as not to repeat that cycle, as wise people say.

Do you ever feel alone in your pursuit of the truth?

Yes. One is often lonely in such a battle. But in tough times, when I’ve needed sympathy, I’ve had the support of friends and colleagues. I’ve also often gotten support from strangers who call or write in to encourage me, to say that they believe me and stand by me.

What makes you optimistic — for journalism, for society, and in your personal life?

The conviction that there’s always light after the dark. This is true both for individuals and for societies and the world as a whole. It’s the same with journalism: it abides by the laws of dialectics; therefore, the journalists who come after us will always be better in their craft.

How do you unwind when you take a break from these battles?

I don’t have much time to relax. Even so, swimming, traveling, driving, and encounters with new places and people help me a lot.

What inspiring story from Stara Zagora would you tell a first-time visitor to the city?

The story of Grandpa Methodiy. He was the first bishop of Stara Zagora, and his secular name was Methodiy Kussev. He was a pillar of local morale, a rebel, and an enlightener whose deeds are an inspiration to every generation. His greatest deed was the creation of Stara Zagora’s unique park, Ayazmoto. Now the authorities are trying to spoil the park with construction funded by European money.

What would you say is your greatest achievement?

I don’t see my job as a series of achievements, and I do not rate accomplishments. However, I am always happy when I see that my work brings value and meaning to people.

What are you grateful for at the end of 2023, and what do you wish for in 2024?

Healthwise, I went through some hardships over the past year, but I managed to recover. I have my friends, my mother, and my cat to take care of as well as my nephews. I would be grateful if God gives me more chances for nice trips and experiences in 2024. Most importantly — and I’m not saying this to look good — I hope that 2024 brings an end to the war in Ukraine and the hostilities in Gaza. I hope that there are fewer natural disasters and casualties on the path of transition that our planet is undergoing.