In 1980, things got really heated at the US-Canadian border.

Maine potato farmers were angry about imports of cheap Canadian spuds forcing them to sell at prices that wiped out profits and drove many into debt. So, they dumped piles of their unsold produce at border crossings, closing off traffic. When the standoff started to get out of hand—a Canadian flag was burned, according to one report, and tensions mounted between protesting farmers and truckers waiting to get their goods across the border—state troopers in riot gear were dispatched to prevent clashes, and the White House decided it was time to intervene.

It flew in Lynn Daft, a young economist who worked on the domestic policy staff of the Carter administration. Although Lynn had no farming experience, he had grown up around farmers and understood their thinking. After a decade and a half in Washington, he also had a reputation for being able to work through conflicts and a track record of reaching agreements across party lines.

At the small border town of Fort Kent, in Maine, Lynn encountered several hundred irate farmers who didn’t mince their words. One farmer told a TV crew that it was “poverty, nothing but damn poverty” that had forced the farmers to such desperate action. A CBC reporter said the farmers were facing “financial disaster” for the third year in a row.

The meeting itself had the makings of a disaster and could have gone very differently. Lynn remembers the one-story building where the meeting took place being surrounded by potato farmers looking in through the windows, the strain and concentration etched onto their faces.

Lynn hadn’t gone to Fort Kent to prevaricate, make promises he couldn’t keep, or appease. He was there to listen. He empathized with the farmers’ plight and assured them the government was paying attention. In his disarmingly gentle yet straightforward manner, he also told the farmers that there were limits to what the administration could do. After a day-long, sometimes edgy encounter, an agreement was reached: the farmers would lift the blockade, and a government task force would be formed to address their concerns.

This wasn’t the only tense situation that Lynn helped defuse during his four years in the White House. The Carter administration inherited a difficult economic situation: overproduction in the agriculture sector had led to falling prices, plummeting farm incomes, and the liquidation of livestock herds at an unprecedented rate. Many farmers were hurting and made their hurt known to those in Washington. Rallies and protests erupted throughout the country between 1977 and 1981. In February 1979, thousands of farmers in tractors blocked the National Mall in Washington, DC for weeks, a protest action now known as the 1979 Tractorcade. (One of the participating tractors can be seen at the Smithsonian.)

Lynn estimates that he held several dozen meetings with hundreds of farmers during that time. “Part of my responsibility here [was] to be a listener, to have an open door to outside interests,” he told a Presidential Papers staff interviewer in 1980. Lynn did make sure the administration listened to the protesters’ concerns, but he also tried to make the demonstrators see the constraints on government action. His quiet leadership can be at least partially credited with the favorable outcome of the negotiations. In an interesting twist, one of the protesters’ leaders eventually came to work for him, at the White House.

Lynn is modest about his ability with people, jotting it down to being “analytic and factually based.” He is adamant that “I don’t want people to like me because I am bending the truth or saying things I don’t believe. You want to be straightforward and honest, as you understand it. [However], as a scientist, I understand full well that nothing is certain. No theory is immune from being disproved. You don’t want to be so cocksure that what you are thinking or saying is going to stand up to everything… You have to be rather humble about it.”

Humility, honesty, integrity—these qualities were nurtured in a family of grain entrepreneurs in small-town Ohio. Central to the family grain elevator business were the grain storage towers—a fixture as well as the tallest feature of the rural US skyline 50 years ago. The towers were symbolic of how Lynn’s father and grandfather understood their role as successful entrepreneurs in the community—as having to stand taller than the rest, lead by example, and be their community’s pillars. His grandfather went on to become their town’s mayor.

The family lessons served Lynn well in his Washington appointments. They helped him work across ideological divisions and win over many who disagreed with him, earning him broad respect. He was a favorite to lead transition teams and an asset to both Republican and Democratic administrations. A Democrat, he was first drawn to policy work in the mid-1960s, during the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson. His training as an agricultural economist earned him an invitation to join the National Commission on Food Marketing and later the National Advisory Commission on Rural Poverty. He then went on to serve at the US Department of Agriculture. Unlike many of his colleagues, who left the USDA with the election of President Nixon and the change of politics at the White House, Lynn stayed on. He truly enjoyed working in the agricultural policy sphere and believed lasting policy change would benefit from continuity in the USDA; he was also uniquely suited to work across party lines.

In fact, his first trip to Bulgaria, in 1974, came about because of his excellent professional relationship with a Republican policymaker, Will Erwin, who would eventually recommend Lynn to replace him on the board of directors of the Bulgarian-American Enterprise Fund. But before that, in ’74, Erwin invited Lynn to join the US delegation at a United Nations–sponsored conference on rural development in Plovdiv, Bulgaria.

Nothing during that first inauspicious week in Bulgaria betrayed the fact that he would end up devoting almost a quarter century of his life to the country and its economic advancement. He and his wife, Linda, who accompanied him on the trip, felt watched—by minders at hotels and conference halls and police escorts on the way from Sofia to Plovdiv and the Black Sea coast—and were sure their luggage was searched on multiple occasions. A paper Lynn contributed to the conference was misinterpreted as hostile to the Russians. He felt nothing but relief when the plane took off a week later.

He didn’t know it at the time, but he’d be returning, 22 years hence, in a very different mood—with a sense of excitement that he’d be able to contribute to the transition of the country from authoritarianism to democracy.

In Lynn’s telling, his early years at the Bulgarian-American Enterprise Fund were marked by “a great deal of listening” on account of his being a junior director. Yet his quiet leadership and agricultural expertise helped the Fund and later the America for Bulgaria Foundation make the right calls on a number of occasions and navigate complicated investments and both internal and external friction.

An investment of the Fund Lynn was closely involved with was Ameta, the poultry producer, which from a failing business went on to become the country’s largest supplier of poultry products. “That was an interesting experience that continues to reap psychic rewards for me,” Lynn says. “I am proud of [Ameta]. I am proud that we stuck with it and we identified a couple of people who could make it the success it is.”

As far as ABF’s work, Lynn sees that as “an opportunity to think in a larger sphere, to think beyond simply providing finance and guidance in investment. The Foundation offered opportunities to work on other things, [things] that a financial institution wasn’t equipped to handle, whether it was the rule of law or [the] effect [of] corruption or technologies that the US had that could be applied.”

High points for Lynn are ABF’s investments in Bulgarian agriculture such as the projects to improve soil conservation and introduce precision farming techniques. The Foundation’s longstanding investments in Bulgarian education are another source of pride. “Every time you go to a school and observe what’s happening to the kids with the investments that have been made, whether it is in equipment or a better-looking school, teachers with more effective teaching techniques… you come away feeling really good about it. I don’t recall ever going to a school where I didn’t feel elated,” he says.

Lynn is careful not to overstate the board’s role in either the Fund’s or the Foundation’s work. “The idea [behind the two organizations] was to take the US experience and let Bulgarians see what that is and figure out what part of that suits their purposes,” he says. He sees the success of the Fund as hinging on the caliber of the people on the ground and on the board’s ability to listen to them. “Having the right people was critical, and the most important right person was Frank Bauer [the Fund’s and later ABF’s president]. He was uniquely qualified for that job.”

For an individual as generous with his praise as Lynn is, he is remarkably humble about any tokens of gratitude or appreciation directed at him. Forty years ago, in Maine, a potato farmer gave Lynn his pocketknife in gratitude for ending the standoff. “A keepsake I still treasure,” Lynn says.

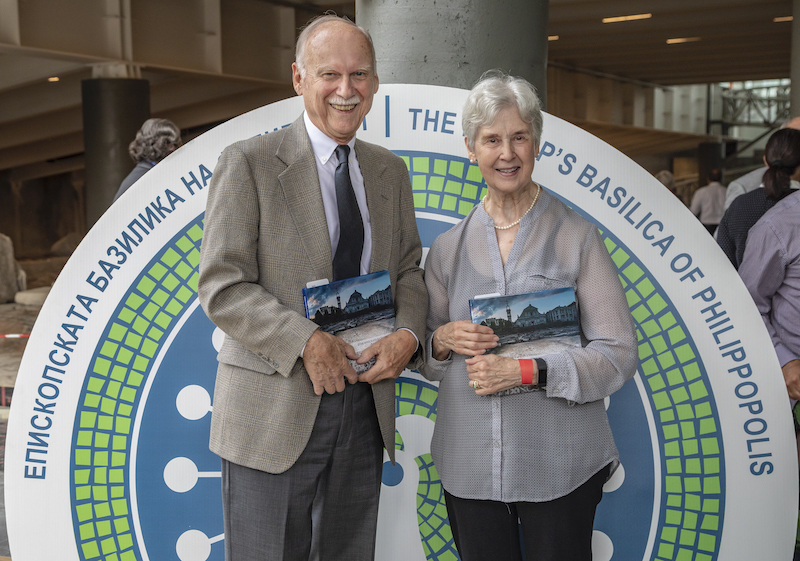

Today, the outdoor theater at the American College of Sofia’s America for Bulgaria Campus Center bears Lynn and his wife, Linda’s names in recognition of their support over the years. Lynn was so surprised and overcome with emotion at the theater’s unveiling, all he managed to say was “Thank you.”

No other words were necessary. As always, Lynn preferred to listen.