Paul H. Pardew is a retired major general with 32 years of distinguished service in the US Army. He is also the son of former US ambassador to Bulgaria James W. Pardew and his wife, Kathy.

Wishing to continue his late parents’ legacy of friendship and support for democratic processes in Bulgaria, Major General (Ret.) Pardew accepted an invitation to join the board of the Anti-Corruption Fund in an advisory capacity. His experience in military procurement makes him uniquely placed to advise Bulgaria’s largest nonprofit dedicated to investigating and publicizing corruption at all levels in the country.

Major General (Ret.) Pardew made a career out of fighting corruption in the Army, one of the six branches of the United States Armed Forces. In his last assignment, he led the Army Contracting Command, the Army’s largest procurement organization of 6,000 acquisition professionals and with an annual budget of $483 million. Under his leadership, the organization managed a $500 billion portfolio of Army procurements and negotiated $9.1 billion in cost savings for fiscal year 2020 alone. In previous leadership positions related to acquisition, he drove effective oversight of contractors, contracts, and resources.

Major General (Ret.) Pardew has been deployed to combat on several occasions, and among his many decorations are the Distinguished Service Medal, Defense Superior Service Medal, and Legion of Merit. He has a bachelor’s degree in history from the Virginia Military Institute, an MBA from Old Dominion University, and a master of science degree in national resource strategy from the Eisenhower School, National Defense University.

We talked to Major General (Ret.) Pardew about his experience professionalizing procurement and rooting out corruption in the military and about his plans as a member of the Anti-Corruption Fund’s advisory board.

America for Bulgaria Foundation: You were here for the dedication ceremony of Ambassador James Pardew Street in October 2022. Was this your first time visiting Bulgaria?

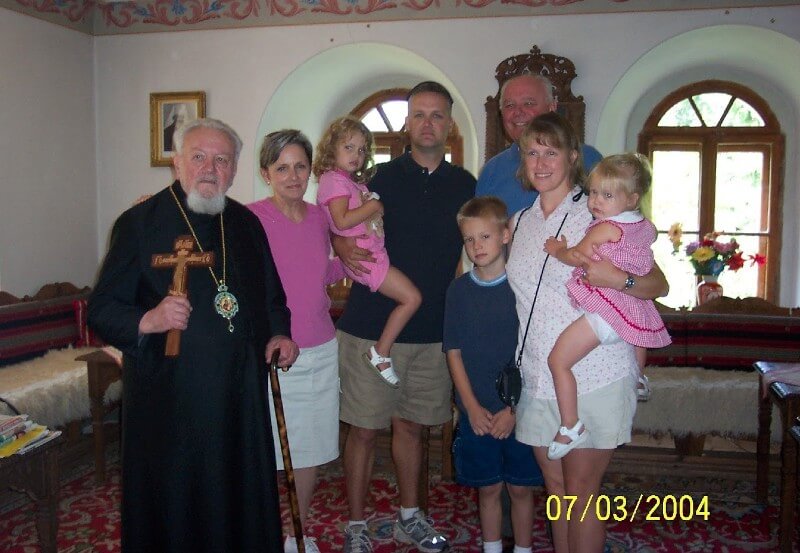

Major General (Ret.) Paul Pardew: This was my second trip. My whole family came in the summer of 2004. We stayed for two weeks, at the residence [the former US ambassador’s residence, ABF’s new home since 2021, ed.]. My dad took us to as many places and events as possible. We went to ballet practice; we met four or five separate artists. It was a great trip.

I’ve been to a lot of countries in my life by virtue of being in the military, but Bulgaria is a gem. That’s what my parents loved about it. It’s this undiscovered gem that people would love if they could just go and see it. My parents took us to Veliko Tarnovo, they took us to Gabrovo. The place I really liked was Tryavna. I am a woodworker, so that’s why I am fascinated by it. We also went to Bozhentsi, where I took my kids to a farm to see where milk comes from.

It was an honor for my father to be recognized. I couldn’t pass that up. I felt it was my personal responsibility, and it also seemed like a natural fit for me to continue my parents’ legacy. They came back to Bulgaria every summer until their health wasn’t good enough for them to return. My parents’ house in the United States was an art collection that was largely Bulgarian. My parents donated that art to Arkansas State University, where they went to school, and it can be seen there today. For me personally, I had nothing but good experiences with Bulgarians and Bulgaria itself.

ABF: You have had a long, distinguished career in the United States Army. What attracted you to a life as a military man?

Maj. Gen. Pardew: I was actually born in Frankfurt, Germany, in an army hospital. When we came back from Germany, my dad went to Vietnam, and my mom and I stayed in their little hometown in Arkansas. Both my grandfathers were in the Second World War, and when I started doing genealogy, I found out that my family traces back to the American Revolution. So, in terms of service in the US Army… that was my natural path. I have loved the military from the moment I was born, and still do. I am still involved in helping the US Army.

ABF: The bulk of your professional experience was in leadership positions in procurement — an area that is hugely vulnerable to corruption. What instruments did you have in place in the Army Contracting Command and in prior appointments to ensure that conflicts of interest could be minimized or prevented altogether?

Maj. Gen. Pardew: Back in 2003, the United States Army procurement experienced a corruption scandal. We had a big investigation and a board of inquiry called the Gansler Commission, which studied the Army’s contracting process and produced a report that guided changes. My career rode the implementation of those changes and the anti-corruption effort in Army contracting. After that, the Army invested in professional contracting people, both military personnel and civilians. As an example, we put in place processes that made sure we could put all conflicts of interest aside. So, as I went through my career, I had to declare any companies I had interest in. If I had a sizable enough interest in a company, I’d have to exclude myself from the procurement. This is a requirement for all our procurement people in order to protect the integrity of the system.

Moreover, no single person is the decision-maker on procurements, whether they are small or big. There are normally multiple people in the chain, including the guy working on it on a day-to-day basis, a contracting officer above him, and legal staff. There are thresholds for reviews for all types of things. So, no one entity can ever say, “I am just going to give the contract to this one company.” Not only that, but these organizations can be inspected from above and from outside. What you have is total visibility of what the procurement system is doing.

We do have people who try to do things, but as I always used to tell my people, “If you try to cheat the government, you are going to get caught.” There are so many steps in the process where you are putting your name on things that the paper trail will eventually catch up to you.

We have a thing called the appearance of impropriety: if it looks like it’s improper, then let’s not do it. We try very hard to ensure that what we are doing is appropriate, and sometimes it slows down the speed of the procurement, but that’s an acceptable cost. Additionally, we strive for a fair and equitable competition amongst our contractors.

We put a structure in place, the Army Contracting Command, ensuring that everything was appropriate and proper, and it took us a decade to grow it out. We increased the staff’s professional training and then built the oversight functions over all of it so that if someone wanted to do something, eventually they’d get caught. That alone is a deterrent.

During my three years as the ACC commander and two years as the deputy prior to that, I don’t remember any significant corruption incident.

ABF: In your experience, how key is the establishment of the right screening criteria for procurements?

Maj. Gen. Pardew: The one thing we fought against was people who’d come in and say, “I want the selection criteria to be these five things,” and they made them so restrictive that only one person could win. We weren’t going to do that. We always wanted more competition because more competition is better, drives your prices down, builds your economic base, etc. Our selection criteria might be strict, but they aren’t going to choke the competition down to one contractor.

There are monopolies out there, and you have to fight through them if you can. If you have more competition, you will have less corruption because the cream is going to rise and people will be watching.

Then we need an OCI [organizational conflict of interest, ed.] mitigation plan. If there was somebody in the procurement system that was a part owner of a company that was going to compete, I would cut that person away from the procurement before it even started. Because if the person is tied to the company, and you don’t mitigate that connection before you go through the selection criteria, we throw the company out. Because it is conflicted, it is out of the pool. Once we discover the conflict of interest, it makes them non-competitive in that government procurement going forward.

ABF: Should all government contracts be awarded through competitive, public procedures, or can there be exceptions?

Maj. Gen. Pardew: Don’t get me wrong, we do sole-source, but that tends to be largely on smaller acquisitions. Currently, the US Army is procuring two new helicopters; those have been and will be competed in order to get the best helicopter against the requirements needed by the Army. No one company could go straight in and win that without competition in our system.

There are sole sources, but they are heavily regulated by our rules/laws. For example, a company might have proprietary materials, or somebody might have a dataset that no one else has. So, we will document that very heavily and take it through our lawyers. We actually have to publish something online that says the government intends to award a sole-source contract. If someone sees that, and they come in and say, “I can do it, too,” that causes us to back up and reassess whether we have a true sole source or not.

We’ve sole-sourced in military and national emergencies, too. That’s usually when you have a military operational situation, or maybe an earthquake or something similar happens. Then your sole source is someone who’s usually worked with you before, but those largely aren’t going to be seven-eight-year contracts.

You can run into true sole sources. Sometimes parts, such as parts for old vehicles, are only made by one company. But, literally, we go and write that out. We make our people go and check the market, making sure there is nobody else. Then they have to sign that they’ve done the research, and there is only one company. In federal procurement in the United States, you are going to have multiple signatures on most of the documents. There are multiple eyes making sure they are done appropriately.

ABF: These people will have different job descriptions, but there must be certain qualities that you look for in selecting people to work in procurement. What are those?

Maj. Gen. Pardew: One is business acumen. We try to get people with business degrees. I’ve got an MBA in finance, and I had to have that to be a contracting professional. In contracting, you are talking to other businesses. You need to understand how they think, how they operate, why they negotiate the way they do.

We had people with security clearances to do the work, as some of it is classified. Actually, a lot of it is classified, so we had background checks on almost everybody.

So, these are usually highly skilled people with advanced degrees. Then we train them and put them on a path that they would want to grow in. A lot of people come in right after college, and they stay, grow through the organization, and build a reputation out. The senior people that we trusted with big procurements had been in the organization for a long time. They had background checks, and we checked references on these people and sometimes even their finances.

Judging personal integrity is a contact sport. You have to get to know somebody. You also need to know what’s going on in these people’s lives. People are complex and challenging to lead and manage. People can get divorced, their parents can pass, their finances can be in the tank. All those impact people, and it’s hard to know that. Most of the time when we saw corruption, there were other factors why they got themselves down that path.

ABF: How do you feel that your prior experience can contribute to ACF’s work?

Maj. Gen. Pardew: My whole career rode on the anti-corruption wave. When I visited Bulgaria in 2004, ACC didn’t exist. We now have a professional workforce that has an appropriate level of compliance checks and oversight, so it’s very, very hard to be corrupt in the Army’s contracting system now.

We are not perfect, but I do think we are a rule-of-law country. Corruption is not something that the American people respond well to in their politicians and certainly not in their military leaders. The military in the United States is held in high regard here largely because it is a meritocracy and because it attacks its problems. I grew out of attacking one of these problems.

Where I think I can help is my experience. You have to professionalize your procurement system, you’ve got to enforce the rule of law, and you’ve got to put a level of compliance and transparency in place. I don’t think any politician or senior official should have any influence over government procurement at all. They shouldn’t have inside information, they shouldn’t be able to pressure the procurement people, and they certainly shouldn’t be in the decision-making.

The biggest thing is transparency. ACC did most of the Operation Warp Speed contracts [Operation Warp Speed was a public-private partnership in charge of Covid-19 vaccine and therapeutics development in the United States, ed.]. Because there were so many interested and concerned people worried about undue influence on those contracts, they were all published in the public domain. So, on anything we did from a procurement perspective, we posted the documents online as soon as we were done with them, so reporters, congressmen, other government officials, state officials, etc., could see what ACC, the Air Force, and other entities were doing. We never had a problem.

My number one job at ACC was as a protector of the procurement system — ensuring that the procurement system didn’t get corrupted and then ensuring that everybody below me believed that their job was to protect the system. That takes a level of training and effort and oversight. I can’t mention the oversight piece enough. What gets watched gets done.

ABF: In your experience, what are the most effective ways of fighting corruption, at any level?

Maj. Gen. Pardew: Somebody said to me once, “Corruption is like dust in the air. You don’t see it unless you shine a light on it.”

I come back to a couple of things: Your organizational structure for procurement has to be separate from your decision-making authorities, so the procurement people can uphold the laws that are in place and so they can’t be influenced by outside people. Then you have to have transparency. Third, there has to be a level of oversight and reporting up and down the chain, so the work stays within the confines of the laws we are upholding. That’s not easy. It takes the right people with the right training, and they have to believe in the system.

We have corruption in the United States and other problems. We are not perfect, but I think the main difference is [the understanding that] we’ve got to recognize it and we’ve got to attack it.

The Anti-Corruption Fund works with the long-term support of the America for Bulgaria Foundation.