Integrity is the opposite of corruption, according to Philip Gounev, and we can all fight corruption by not benefitting from or giving in to it, and by being ethical in all our dealings, personal or professional. Insignificant though it may seem, personal example does have an impact on the environment: over time, it makes it less tolerant of corrupt behavior. Pervasive integrity is the only lasting way to reduce corruption.

Philip Gounev is a leading expert in EU anticorruption measures and internal affairs and chairman of the board of the Bulgarian Anti-Corruption Fund (ACF), a nonprofit bringing together legal experts and journalists investigating corruption at all levels in the country. As deputy interior minister between 2013 and 2017, he was responsible for the establishment of an anticorruption coordination body at the Bulgarian Ministry of Interior and helped draft the country’s anticorruption strategy.

Philip Gounev began his career in investment and finance in the United States. Back in Bulgaria, for almost a decade between 2003 and 2013, he worked at the Sofia-based Center for the Study of Democracy, where he headed the security and internal affairs research team. Between 2011 and 2014, he was a member of the European Commission’s Expert Group on Corruption.

He has a doctorate in sociology from London School of Economics, a master’s degree in international relations from Columbia University, and a BA from Eastern Nazarene College.

In an interview for the monthly newsletter of the America for Bulgaria Foundation, Philip Gounev talked about the Anti-Corruption Fund’s work and the ways in which citizens can support it. Readers will also receive tips on fighting corruption in their daily lives.

What is the Anti-Corruption Fund and how does it work?

Corruption in Bulgaria is not a hidden phenomenon, and very often it is on the surface. In other words, very little effort is made to cover up schemes, perhaps because the state has been taken over by political and economic circles that have been working with impunity for decades. This type of corruption is not always understood by citizens, but if the dots are connected, the full picture emerges. The purpose of ACF is to help journalists, working in cooperation with experts, investigate and expose large corruption schemes.

Even if investigative institutions wanted to do their jobs, there would often be economic and political interests hindering them from doing so. But if public opinion went in the other direction [against inaction], these circles would have to accept that sacrifices must be made and corruption punished. Even if this does not happen, the fact that corruption is exposed lets the political class know that behavior that would have gone unpunished ten years ago will no longer be tolerated today.

What is different today from ten years ago?

In the 1990s, you had to give a bribe to get a landline or running water or get the cop, doctor, customs officer, or anyone really to pay any attention to you. Gradually, the average person’s experience with corruption has diminished. When you do not benefit from or are not a victim of corruption, you are less likely to tolerate your peers or elected officials taking advantage of it. When more and more individuals do business at real prices, and both companies and people try to be honest, and suddenly it emerges that some politicians saved a lot of taxes, ordinary people take notice and realize it is unacceptable.

Why is corruption so persistent in Bulgaria?

There are studies showing how shortages in the socialist system forced people to continually search for connections and build informal networks in order to get what they needed. Then, you start applying all these informal connections and networks and survival techniques in a market economy, in a democracy, and they become the soil in which corruption thrives. Corruption in small island countries is usually very difficult to identify and the hardest to fight. Everyone knows everyone else; everyone is connected. It is very difficult to regulate these relationships and to have honesty, principled governance, and a lack of nepotism be the norm. In small countries and societies, these processes are very difficult to regulate.

I don’t think that there is a country free of corruption. There is always an economic or political group taking advantage of its ability to divide resources unfairly. That is why I don’t think we can eliminate corruption, but we should be able to keep it under control and reduce it over time.

And how does the Anti-Corruption Fund fit into this process?

We want to expose corruption cases and to encourage the prosecutor general’s office and the interior ministry to investigate corruption. We are not a think tank that offers models and shows how the system should be organized, what judicial reform or interior ministry reform should look like. ACF’s mission is more limited: we believe that corruption schemes should be exposed, that society should be aware of them and should not tolerate them, and that institutions should investigate them. Our mission is to stimulate these processes and make citizens uncompromising toward corruption. One of the areas in which we want to work is raising awareness of corruption among citizens and businesses. We want to conduct and support even more independent investigations. Partnering with independent journalists, by offering them funding or expertise, is part of our long-term mission.

Last year, with the support of the Dutch government, we trained investigative journalists from Bulgaria and the Netherlands to build their capacity to conduct such investigations and work with information sources. It’s not always easy to track offshore companies, work with public databases and information, and interpret your findings. We also had a project in several Bulgarian municipalities training local institutions and communities to take action against corruption. Now, with support from the Norwegian Financial Mechanism, we are expanding this work to ten more municipalities to help them become more transparent. We will work with local businesses and journalists to equip them to monitor and respond to cases of corruption more easily.

How is ACF funded?

ACF was established with funding from the America for Bulgaria Foundation, but over the last year, we have taken various steps to reach out to a wider range of donors. Our other major source of funding was the Open Society Foundation. We are now working on an international project funded by the Norwegian Financial Mechanism. Also, with the support of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, we jointly developed a tool to monitor investigations of high-level corruption by the prosecutor general’s office and other investigative bodies. The Friedrich Ebert Foundation is another source of support. We are also working on several joint initiatives with the Dutch government, one of which is a project to implement EU whistleblower protection legislation.

Virtually no one wants to fund journalistic investigations. Most donors focus on more positive and politically neutral activities. Therefore, the only way to finance investigations is either through specialized funds for investigative journalists or through independent donations. This year, we were able to attract small donations from citizens online.

We do not want to be funded by private businesses in Bulgaria because this could very easily be interpreted as dependence, as if we were putting ourselves in their service. We are a politically independent organization, and we are also independent of private economic interests.

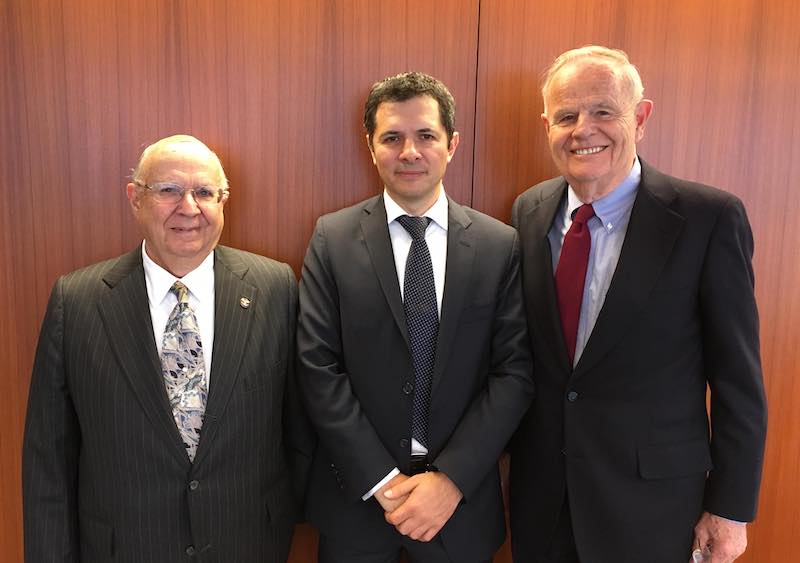

We had a big breakthrough during our trip to the United States in 2019, where we met with Bulgarians living there and Americans with ties to Bulgaria but who have no direct economic or political interests here. We were able to raise funds to support most of this year’s investigations.

What are the costs associated with an investigation?

An investigation must support the independent journalist conducting it and cover the various costs involved: travel, filming, paid access to databases, etc.

How can ordinary individuals support the activities of the Anti-Corruption Fund?

We have all been confronted with small-scale corruption that affects us personally: traffic police bribery, administrative corruption. This type of malfeasance is widespread, but it is low level. We do not investigate petty corruption cases; we believe that administrative reform is the main way to combat petty corruption. Because the people who make the rules are usually behind the major corruption schemes, the only way to stop these is through investigations. Ordinary people do not know about them; business is sometimes aware of them. We have been alerted by companies that witnessed corruption while participating in public procurement tenders.

When ordinary citizens report cases of corruption, we offer guidance and direct them to the right institution, because they often do not know where to take their report. If you are asked for a bribe by a local traffic police officer and you report this to the local police department, there is always a risk that this will be covered up. However, if you take your report to the internal security department of the ministry of interior or the interior ministry inspectorate, or to the prosecutor’s office, such a cover-up will be more difficult. Even companies are not always sure which institution to turn to.

Many citizens and companies think it is pointless to report corruption, often because they have no evidence or only suspect it. But the more reports there are, the more likely it is that there will be consequences. The only way to resist corruption is to report it. Politicians in Bulgaria have no interest in covering up small and medium-sized corruption. Only big corruption is concealed.

In what other ways can one support ACF’s work?

All online databases currently in existence, such as the land and property records databases and so on, help to analyze real estate and other acquisitions and to detect corruption schemes. We have many ideas for IT tools that could be developed—such as software that could quickly search the property records database. If an IT company decided to donate 5 percent of its time to help us develop them, it would be really useful. Such support would really advance the cause [of fighting corruption].

What can each of us do to fight corruption?

When you encounter it, do not tolerate it—report it. Do not partake of it by paying a bribe. Very often, businesses give in to extortion. This is not corruption until you pay up. For example, if you are stopped for speeding in Bulgaria, the officer cannot ask you to pay a fine on the spot. They can give you a speeding ticket, which you will have to pay, but later. The only correct response in this case is: “If you caught me, I’ll get my speeding ticket in the mail then!” If they ask you for money, this is extortion. Both businesses and citizens fall prey to extortion often because they are not well informed.

When an individual or a business is a victim of an extortion attempt, first, they should try to resist it and refuse to pay. Second, they must report the incident to the right institution. Even if they do not catch the officer in question, because you have no evidence, if they receive five independent reports about Officer X, sooner or later he will be investigated and punished. Things were different years ago, but today corrupt behavior will attract attention.

You do pro bono work for ACF. Why spend so much time and energy without financial gain?

I am the chairman of ACF’s board, which has a supervisory function. We are there to support the fund’s work, offer ideas, and help the organization sustain itself financially.

Volunteering is something I have done for years. To me, this is work for the benefit of society, and corruption is the root of many social problems. For example, corruption in the traffic police costs human lives. Every year, people die because they get away with speeding. In general, corruption affects many aspects of personal and public life. For me this is a meaningful cause.

Can we beat corruption?

Let’s say I’m a moderate optimist. I do not believe that corruption will disappear. For years, we have observed, in western societies as well, the state’s takeover by political and economic elites, a trend that is likely to persist. What we have to do is oppose them and restrict their access to public resources. Bulgaria is getting richer—through economic growth and the growth of incomes. There is more for people, but there is also more to steal. The scales must be tipped in the public’s favor.

You can make a difference in fighting corruption, too! Support the Anti-Corruption Fund.