It has become a tradition for the America for Bulgaria Foundation team to visit Belene at summer’s threshold — when the town and its environs are bustling with life again after a chilly Danubian winter. It is then that the many layers of the place are most obvious — its stunning natural beauty and tourism potential marked by a darker side.

On our visit this year, on May 13 and 14, we were joined by our partners from the Sofia Platform Foundation, historians Daniela Koleva and Momchil Metodiev, and foreign diplomats.

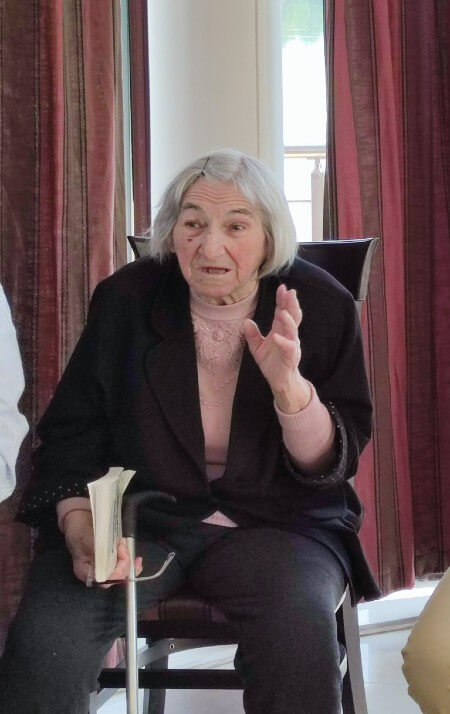

We were also accompanied by two Belene concentration camp survivors — 79-year-old Khalil Rasim and 94-year-old Tsvetana Dzhermanova. Together we honored the memory of the thousands of victims of Bulgaria’s former totalitarian regime.

We are grateful to the mayor of Belene, Mr. Milen Dulev, Mihail Marinov from the Belene Island Foundation, Father Paolo Cortesi, the local community, and the staff of the Prestige Hotel for the nimble organization, warm welcome, and hospitality throughout our stay!

The following photo story is a vivid portrait of our trip.

In early summer, Belene Island (also known as Persin Island) resembles something out of a National Geographic documentary on natural habitats that refuse to be tamed by human presence: there’s lush vegetation that seems to grow back overnight, hundreds of bird colonies, swarms of insects…

…and grass that thrives in asphalt!

Bulgaria’s largest island, Persin belongs to the Belene Islands Complex—since 2002 a protected wetland area of international importance that is home to hundreds of rare birds and plants. The island is a paradise for birdwatchers and nature lovers. What is more, the tens of miles of paved track around Belene Island would make it an ideal destination for recreational cyclists and runners as well.

The America for Bulgaria Foundation supports a number of projects to aid tourism development in the area. One of them is the Dalmatian Pelican Festival, celebrating the recent return of the eponymous bird to Belene Island. This endangered species is one of the largest flying birds on earth.

Prior to 1989, the island hosted the infamous Belene concentration camp, where political prisoners were detained without trial and subjected to back-breaking labor and inhuman treatment, often for years, some of them never to return to their homes. To this day, there is a state penitentiary in the western part of the island, restricting access both to the nature reserve and to the site of the erstwhile concentration camp. Visitors need to apply for a permit from the Bulgarian Ministry of Justice in order to visit the island.

The sign at the site’s entrance reads: “Yes, man sounds proud! Labor Reeducation Facility – Belene. Site 2.” (The sign has been temporarily removed.) One of the Site 2 buildings can be seen in the background.

We laid flowers in memory of the victims of the totalitarian regime in Bulgaria in front of the still unfinished Belene memorial.

We also visited some of the remaining buildings from the camp’s Site 2. A panel from the “Breaks in the Wall” exhibit is visible through the bars. The exhibit of portraits of Belene camp inmates was hand-drawn in secret by Petar Baychev, a lawyer, artist, and former inmate. The exhibition can be seen at Site 2 of the Belene concentration camp.

Tsvetana Dzhermanova and Khalil Rasim spent a combined quarter century in labor camps. The guests’ encounter with the two camp survivors, which was moderated by Sofia Platform’s Louisa Slavkova and historian Momchil Metodiev, was emotional as well as educational.

Tsvetana was a teenager when she first became attracted to the leftist ideals of anarchism, particularly its insistence on justice, freedom, and equality for all. Despite the ideological similarities between anarchists and communists, however, after 1946, the regime undertook a series of purges against its one-time allies. Tsvetana was just 20 when the former “ideological sister” became “an enemy of the people.”

Tsvetana speaks about her time in the camps “without a shred of vengeance in my soul and with the great desire that what we went through should never happen again. I feel obliged to tell of the Bolshevik system that came to power in the name of ‘freedom, brotherhood, and equality’ but forgot about these ideals once it took control.”

At 23, Khalil Rasim was sentenced to 20 years in prison for espionage without any evidence proving his guilt. He spent 14 years in the Stara Zagora prison. After he refused to change his name during the so-called Revival Process in Bulgaria, he was deported to Belene in 1985. After spending a year and a half there, he was interned at Valchedram, near Montana, for another three and a half years. He was extradited from the People’s Republic of Bulgaria in May 1989. He returned to Bulgaria after the regime change.

“I am happy that I can tell you about what I lived through so that no one would ever have to live through it again,” Khalil says.

The sleeping quarters Khalil shared with other inmates in Belene still stand and can be visited.

Rasim Berrak (right) invariably accompanies his older brother in meetings with students of the recent past’s history in Bulgaria. Rasim settled in Istanbul after their family was expelled from the country during the Revival Process in the 1980s. He built a number of successful businesses, an aviation and a construction company among them. He never severed his ties with Bulgaria, though: his son lives here, and one of his businesses makes cosmetics infused with Bulgarian rose oil extract.

Economically, Belene didn’t fare as well as Khalil’s brother. Once envisioned as one of the main energy centers of the Bulgarian north, Belene today is dotted by gutted apartment buildings still waiting for the workers that were to staff the two failed energy plants. Those of Belene’s residents lucky enough to be employed mainly work in construction, manufacturing, and agriculture.

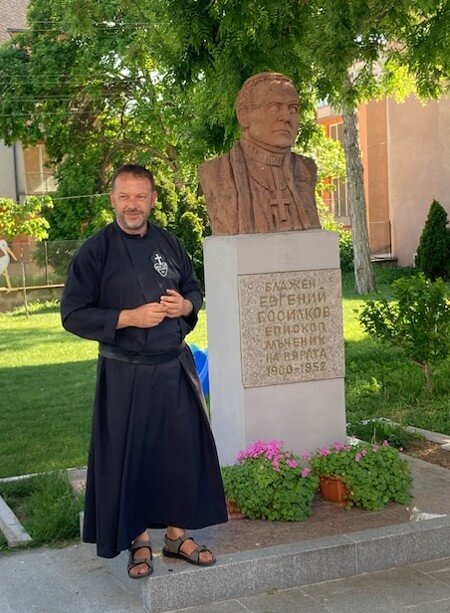

Belene is home to a small Catholic community and several landmarks of interest connected with western Christianity: the first and only monument to Pope John Paul II in Bulgaria and two Catholic churches, one of which is a cultural monument housing the sanctuary of Bishop Eugene Bossilkov, who was beatified by Pope John Paul II.

Spending time with Father Paolo Cortesi (pictured here) is part of the Belene experience as well. An Italian by birth but a citizen of the world by persuasion, this down-to-earth, sharp-tongued polyglot Catholic priest is your best guide to Belene, town and island. Both his tireless work to preserve communism victims’ memory and his efforts to inject new life into the local community have earned him respect nationwide. He was the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee’s Human of the Year in 2017.

The area’s natural beauty, cultural heritage, and human capital are rich resources ready to be tapped into, and a few enterprising locals are already using this potential. Hotel Prestige, perched on the riverbank overlooking Belene Island, is well managed and offers good price-quality balance. Go back in time by visiting the ruins of first-century Roman military fort Dimum, next door to Hotel Prestige. You can also book a fishing trip or a boat ride to nearby islands with local fishermen through your hotel.

Belene is part of Dunav Ultra, the popular bike route that connects Bulgaria’s northwesternmost city, Vidin, with the Black Sea. Within biking distance are the towns of Svishtov and Nikopol, where history buffs will find plenty of ancient and medieval ruins to linger around as well. The photo was taken in 2021 in front of Belene’s own ancient landmark — the first-century Roman military fort Dimum.

Founded in 2013, Sofia Platform works in the field of civic education to help advance Bulgarians’ democratic culture and knowledge of their country’s communist past. The annual summer school on memory and remembrance it organizes with support from ABF challenges young adults to determine why and how contemporaries should remember this time and what lessons for the present history can teach them.

Khalil has been joining the annual summer camp almost every year since the program’s inception.

This year’s summer school will take place between June 26 and July 2. The application deadline is May 25.

Photos by Petya Valkova, Krasimira Butseva, Louisa Slavkova, Tsanislav Genchev, and Sylvia Zareva