Paul Orselli is a museum exhibition designer whose goal isn’t just to get more people into museums. He wants to turn museum visitors into loyal fans!

Paul has been helping museums develop relationships with local communities and guests for over 40 years. In March, he will share his experience with Bulgarian museum and gallery professionals at the first edition of the America for Bulgaria Foundation’s newly launched Muse Academy in Dryanovo.

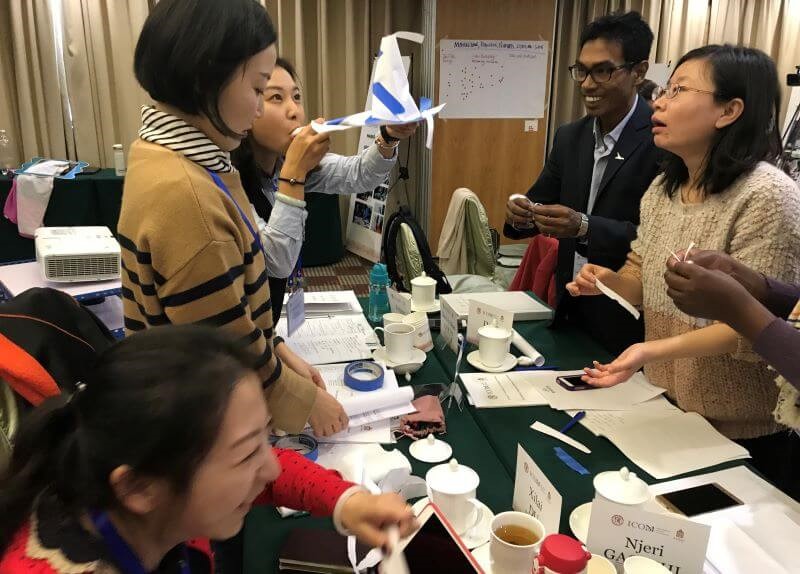

Over the course of a week, Muse Academy will equip participants with the tools to create compelling exhibits and tell powerful stories that will keep visitors returning for more. Paul will be joined by US colleagues Christina Ferwerda and Jamie Lawyer as well as by Bulgarian museum designer Martina Deneva-Venkova and the team of Atelier 3, an award-winning architectural studio specializing in cultural heritage conservation.

Paul believes passion is a key ingredient in creating a successful exhibit. “If you can’t be excited about an exhibit idea, why do you think a museum visitor is going to be excited?”

His own compelling work, which he does through his company POW! (Paul Orselli Workshop, Inc.), is on display at museums and cultural institutions worldwide, such as the New York Hall of Science, the Exploratorium, the National Science Foundation, Science Projects in London, and Muzeiko in Sofia.

In addition to telling us what makes him tick and how successful exhibitions come together, Paul provided a sneak peek into what he and his co-lecturers at Muse Academy have prepared for the first class of participants in March.

America for Bulgaria Foundation: What do we mean when we talk about museum experiences, and why are they important for attracting visitors?

Paul Orselli: I did a blog post that compared a successful museum experience to a successful dining experience. When you go to a restaurant where you really enjoy the experience, what are the qualities of that experience? It starts as soon as you walk in: you feel like you are welcome, like you are oriented. You think: “This is exciting. I like the looks of this place. I feel comfortable here. I am going to have a good time.” As you go through the process, things are set up so your needs are anticipated. Somebody fills up your water glass without you asking for it. The people you were with are enjoying it, too.

A lot of museums and museum people think only about the stuff inside. We have the Mona Lisa, we have Thracian gold, we have a giant ammonite, a rock that’s a million years old. That’s great. But the stuff only means something if there are stories attached to it. One of my favorite museum directors, Jane Werner, the director of the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh, always says, “Even more important than stuff is staff.”

Think about a restaurant without the staff. Think about a restaurant experience where people weren’t welcoming, or where they weren’t on top of the food or your orders or your needs. All those things, in some way, are small things, but they add up. A visitor might not be able to articulate why their interactions with staff were important to them or why the stories or the ideas they took away from the experience were important. But when they leave, they had a positive experience. They want to share that experience online or tell their friends or relatives about it. That is really what makes a successful museum exhibit or experience — all these little things [that] surprise or delight or enhance or engage or make people think. Those are things that really stick with people.

ABF: How do you get a museum team to provide such experiences? Is it about their knowledge, or is there something else that matters more than knowledge?

P.O.: If you are preparing an exhibition or an experience, you need to find a way to fall in love with the subject. You need to be so sincerely interested and excited it becomes the kind of thing you share with your best friend or someone in your family. If the people who put an exhibit together weren’t excited about it, it shows. You can pick apart the elements of what goes into an exhibit, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it is a successful exhibit.

There is this sense of the people who make things that imbues their personality, this living, breathing aspect to something. That’s what makes the difference.

When you walk around the Exploratorium in San Francisco — the forerunner for modern science centers around the world — it feels like Frank Oppenheimer, the physicist and the museum’s original director, just stepped away and you are able to walk around his workshop and get a sense of him.

Think about people you know who are really excited about a football team: they wear the team’s gear; they are proud about that. I want to create museum fans — people who are so excited about a museum they wear their T-shirts and not just on game day. If you get them started about their favorite museum, you will get an earful because they’ve got a lot to say and a lot of very positive feelings about that. That’s what any museum designer or developer can aspire to. I want to make something that’s fan-worthy!

ABF: So, passion is a key ingredient, but surely there are dos and don’ts when it comes to exhibit development? What are they?

P.O.: There is not just one way to be an exhibit designer. There are still these guideposts to follow. For example, if you can’t be excited about an exhibit idea, why do you think a museum visitor is going to be excited? There are rules of thumb to keep in mind, but those are just broad frameworks to work within. If you keep those broad frameworks in mind, there is still enough flexibility for you as a designer to make things interesting and try out different ways.

I worked on a historic exhibit for the D&H Canal Museum recently, together with Christina [Ferwerda], one of the co-teachers [in Muse Academy]. The D&H Canal was a 108-mile-long canal dug by immigrant labor with shovels and picks and wheelbarrows in the 1800s. In some ways, it has nothing to do with the present. Most of it doesn’t even physically exist. But we think that story is important to tell.

To me, the question was: Why would you undertake such a monumental task, a crazy difficult engineering and physical labor process? There is a simple answer for that: Coal. It was a crazy idea, but it worked, and it worked until railroads came into play. Then, all of a sudden, the canal became obsolete.

In a way, the canal story is the same story of technology throughout time: we need something that’s faster and cheaper and will make us more money. It had employed thousands and thousands of people and made millions of dollars for many, even in the 1800s, and now it’s gone.

We had four spaces in a historic building, and the first space was the big picture: “Coal is the goal.” In another room, we looked at the economics. Then we looked at the technology. And the last area was set up as an eighteenth-century tavern because that building was a gathering place. We told social history stories. Children and women and people of color and immigrants all played a central role in the development of the canal.

If you were a person who was interested just in general in social history, there was a way in for you. If you were really into science, there was a way in for you. If you just wanted the big picture, there was a way to do that.

This is a sneaky thing. If you want to get people to think about something, but you know that maybe if you come at it from a certain way, they are not going to respond to it, [you should ask yourself]: Is there another way to present information that makes it more comfortable and welcoming and makes them more open to exploring something that they may not have otherwise been interested in.

At a hands-on exhibit about electricity I set up, I remember listening to a parent talking to another. One said that normally they would be afraid or hesitant to experiment with electricity because they didn’t feel they knew enough to talk with their kid about it. “This exhibit feels like we can learn about things together, and I don’t have to know everything about electricity,” the parent said. To me that’s a big win. Not only are you setting up a situation where an adult and their child are going to have a positive experience, but that person will leave having a different way to think about science.

I want to help people reevaluate or rethink things when they come to an exhibit. You can think of museum exhibits as a lens, a way of viewing the world or rethinking ideas.

ABF: How are you going to help Muse Academy participants embark on the process of creating such influential exhibits? What have you prepared for them?

P.O.: The arc of the experiences is going to follow the whole exhibition development process. We start with the focus being on the visitor and the visitor experience. We will move from there to: How do we generate the big ideas, the framework for your exhibit? How do you move into thinking about aspects of interactivity? How do you prototype and test and evaluate these ideas? How do we make these ideas come alive and be interesting, not just a picture on the wall or a dead thing in a case without any context, and then how do we try those things out?

We will have a balance between the theoretical and the practical. The people will be able to do things that they will be able to take away to their own museums. We will have a learning laboratory to play around with — a museum called the House without Nails. The workshop participants will play out their ideas in the House without Nails as a practical experience. That’s an awesome opportunity!

All the workshop participants get to develop and try things out in real time. The people from the House without Nails will be left with a whole batch of ideas that they themselves could look at implementing and trying out. I also want the participants to leave this workshop enthusiastic and energized and with tools and ideas that they can apply to their own situation.

In addition to providing people with tools and ideas, we provide them with hope and encouragement. You can do this! One of the words I learned last time I was in Bulgaria, in 2019, was Mozhelo! [Можело! in Bulgarian, roughly translated as “So it can be done!” or “So it is possible!” Ed.]. I love that word: it is the antidote to “This is not possible.”

It’s the same trajectory for every museum I’ve worked with, whether it’s big, fancy museums or small, tiny, poor museums. You have to find not only the resources, the physical stuff and the money; you need to find the wherewithal within yourself to make that change.

A museum isn’t just picking out a bunch of exhibits and setting them in the middle of a gymnasium. That’s not a museum. There is more to it. [A good museum is the result of a] compulsion to tell stories and share ideas with people.

The application deadline for Muse Academy’s first edition in March 2023 is February 21.