By Ivan Georgiev

It was the late summer of 2012. Evenings in Saint Paul were getting colder, and the oaks and elms along the Mississippi were covered in all shades of yellow and orange.

After the inevitable first few days of orientation, meeting fellow trainees from the World Press Institute, attending classes at St. Thomas University, and jogging on the banks of the river at 5 a.m. in an attempt to overcome the time zone difference, Terry and I found time to get away from the campus. After a short drive, we parked the grand old Chevy next to his favorite pub. Surrounded by the parks of Cathedral Hill, this local landmark is near Saint Paul College and just over 400 yards from my beloved Francis Scott Fitzgerald’s childhood home. Having been a business, politics, and art hub in the capital of Minnesota for more than 40 years, WA Frost became our refuge too. After long days of lectures, meetings, and discussions, Terry and I would talk, over beer and white wine, about journalism, journalists, and everything that had happened to them over the past 60 years. The lessons continued, but without the formal tone that the academic environment inevitably gave them.

After the inevitable first few days of orientation, meeting fellow trainees from the World Press Institute, attending classes at St. Thomas University, and jogging on the banks of the river at 5 a.m. in an attempt to overcome the time zone difference, Terry and I found time to get away from the campus. After a short drive, we parked the grand old Chevy next to his favorite pub. Surrounded by the parks of Cathedral Hill, this local landmark is near Saint Paul College and just over 400 yards from my beloved Francis Scott Fitzgerald’s childhood home. Having been a business, politics, and art hub in the capital of Minnesota for more than 40 years, WA Frost became our refuge too. After long days of lectures, meetings, and discussions, Terry and I would talk, over beer and white wine, about journalism, journalists, and everything that had happened to them over the past 60 years. The lessons continued, but without the formal tone that the academic environment inevitably gave them.

At this point, I have to clarify that my dear friend Terry Wolkerstorfer began his journalism career at a local school newspaper with an interview and a dinner appointment with Louis Armstrong, who was in the city at the time. The dinner never took place—in those days, the presence of people of color in restaurants was frowned upon. After that, Terry studied at what is perhaps the most prestigious school of journalism in the world—the Columbia Journalism School. His career path led him to the battlefields of Vietnam and Cambodia, where he was a correspondent for the Associated Press. Later, he worked for the Jimmy Carter administration in Washington and was active in the efforts to promote American foreign trade interests in Asia.

Terry would introduce me, with undisguised pleasure, to those frequenting the pub. I rushed to shake the hands of judges, businessmen, and artists, to whom I was introduced as a “journalist from Bulgaria,” which, coming from Terry, sounded like a badge of honor.

Terry would introduce me, with undisguised pleasure, to those frequenting the pub. I rushed to shake the hands of judges, businessmen, and artists, to whom I was introduced as a “journalist from Bulgaria,” which, coming from Terry, sounded like a badge of honor.

What was it like to be a journalist from Bulgaria in the company of Pulitzer Prize winners, talented investigative journalists, reporters, and editors in the most influential, even epic, press institutions in the United States? I was fortunate enough to find out during my time as a fellow at the World Press Institute at the end of 2012. And what is it like to be a journalist in Bulgaria and the region? This is something I have experienced every day in the past 12 years. Even though it’s not getting any easier or more enjoyable, I’m not complaining. I have learned two lessons that I want to share with you.

Lesson 1: The readers’ trust is all we have.

At the end of 2017, Alpha Research and the Konrad Adenauer Foundation published the results of a national sociological survey that showed a critically low level of trust in the media in Bulgaria. Only 10 percent of Bulgarians believe that the media in the country are free and what they publish is trustworthy. At the end of 2015, this figure was around 12 percent. As a member of the profession, I don’t find these conclusions surprising. They only reflect a growing tendency over the past several years—dramatically decreasing trust in the media and a devaluing of its public role.

Trust really is the only capital journalists have. Without it, it does not matter what you show, publish, or write. Unfortunately, this textbook lesson is very clear to those who are interested in having a population of readers as responsive as mushrooms—kept in the dark and occasionally fed a load of manure. This way, the occasional bursts of activity hinting at the existence of a civil society become small, transient inconveniences for those in power.

This is happening with increasing frequency. After a news broadcast, I get angry messages from viewers about us failing to report on a given event even though the story in question had actually been the first or second report in the newscast that just ended and top news on our site that day. It’s like some absurd parallel reality.

This is happening with increasing frequency. After a news broadcast, I get angry messages from viewers about us failing to report on a given event even though the story in question had actually been the first or second report in the newscast that just ended and top news on our site that day. It’s like some absurd parallel reality.

A coworker recently described this lack of trust in our work—“They’re all scoundrels” is an often-heard refrain—as “the Peevski effect” (a reference to media owner and MP Delyan Peevski, ed.). Remove the labels, and you’re left with a feeling of weightlessness, which can only be achieved after a long freefall. Until recently, a similar situation could be observed, but on a much more dramatic scale, in neighboring Macedonia, with which we traded ratings this year in the World Press Freedom Index, prepared by Reporters Without Borders (Bulgaria dropped to 111th place, out of 180, and Macedonia climbed to 109th. Ed.). In Skopje, I saw pictures of Euromaidan (the wave of anti-government protests that swept Ukraine in 2013 and 2014, ed.) on the front pages of leading newspapers around the same time that people along the Vardar River in Macedonia began timid protests against the crimes of their government. We are clearly worse off now.

Lesson 2: “Freedom is not free.”

This does not only apply to journalists. Freedom—not only of the media, but any other freedom—cannot be taken for granted. We need to search and fight for it and protect it as we would any other important cause.

This does not only apply to journalists. Freedom—not only of the media, but any other freedom—cannot be taken for granted. We need to search and fight for it and protect it as we would any other important cause.

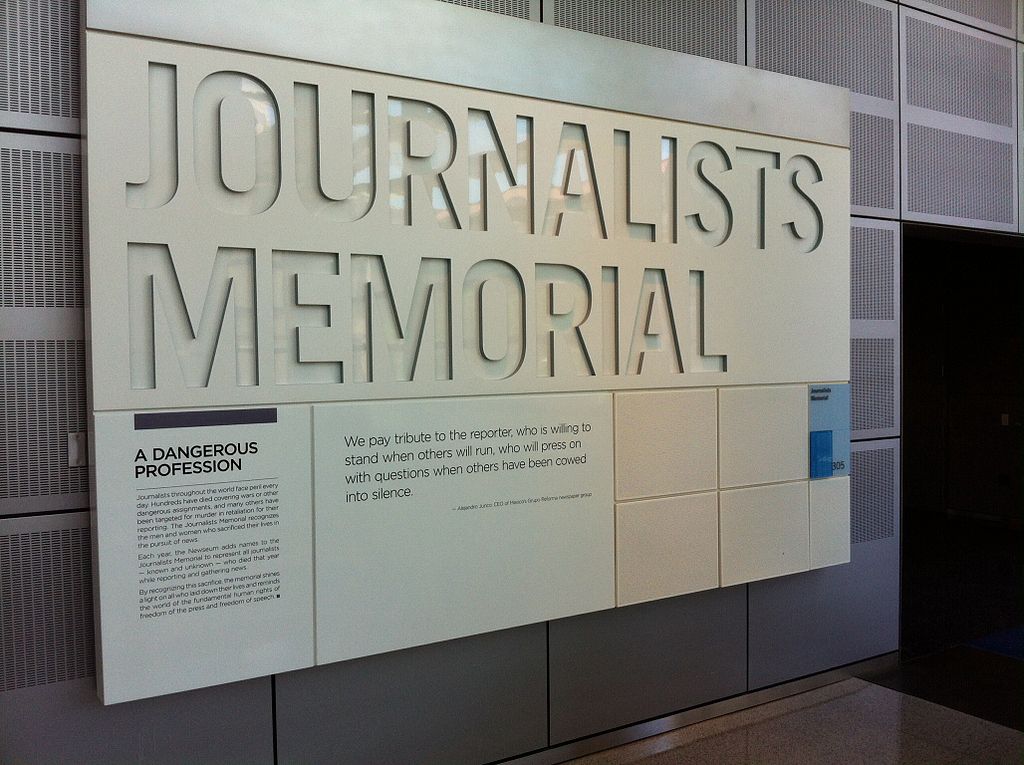

Every society needs strong, independent, and objective media, even if not everyone realizes it. Corruption kills. Journalists and media die, often without a sound. Terry knew this well—he had lost colleagues and friends in the jungles of Southeast Asia. The Newseum’s Journalists Memorial in Washington, DC pays tribute to reporters, photographers, and broadcasters who have died in the line of duty. The names of 2,323 individuals from around the world are etched onto the glass panels of the soaring, two-story structure. Before I left, Terry asked me to look for the name of a colleague of his who had lost his life in Vietnam. I found it, out of respect for him.

My friend Terry is a strong man. When he came to visit me with his wife, Susan, three years ago, he went up the narrow staircase in Hrelyo’s Tower of Rila Monastery despite having had knee surgery just three months before. He drank my grandmother’s strong Macedonian rakia and told my parents that hosts sharing their bread with him was the greatest honor he had had in his life. He had traveled all over the world by then. Fortunately, he is alive and well, taking his work seriously, but not himself—a philosophy I try to emulate, and I don’t hide it.

As a reporter and news anchor for bTV, one of Bulgaria’s main TV stations, Ivan Georgiev has covered some of the leading international and regional events in the past few years.

“Freedom is not free” is an American idiom used widely in the United States to express gratitude to the military for defending personal freedoms. The idiom may be used as a rhetorical device. It expresses gratitude for the service of members of the military, implicitly stating that the freedoms enjoyed by many citizens in many democracies are only possible through the risks taken and sacrifices made by those in the military, drafted or not. The saying is often used to convey respect specifically to those who have given their lives in defense of freedom.

Photo 1. Ivan Georgiev

Photo 2. Journalists Memorial at the Newseum in Washington, DC. Photo by User:Lenitha (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons